I Gave Myself Three Months to Change My Personality

The results were mixed.

Listen to more stories on audm

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

O ne morning last summer , I woke up and announced, to no one in particular: “I choose to be happy today!” Next I journaled about the things I was grateful for and tried to think more positively about my enemies and myself. When someone later criticized me on Twitter, I suppressed my rage and tried to sympathize with my hater. Then, to loosen up and expand my social skills, I headed to an improv class.

Explore the March 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

I was midway through an experiment—sample size: 1—to see whether I could change my personality. Because these activities were supposed to make me happier, I approached them with the desperate hope of a supplicant kneeling at a shrine.

Psychologists say that personality is made up of five traits : extroversion, or how sociable you are; conscientiousness, or how self-disciplined and organized you are; agreeableness, or how warm and empathetic you are; openness, or how receptive you are to new ideas and activities; and neuroticism, or how depressed or anxious you are. People tend to be happier and healthier when they score higher on the first four traits and lower on neuroticism. I’m pretty open and conscientious, but I’m low on extroversion, middling on agreeableness, and off the charts on neuroticism.

Researching the science of personality, I learned that it was possible to deliberately mold these five traits, to an extent, by adopting certain behaviors. I began wondering whether the tactics of personality change could work on me.

I’ve never really liked my personality, and other people don’t like it either. In grad school, a partner and I were assigned to write fake obituaries for each other by interviewing our families and friends. The nicest thing my partner could shake out of my loved ones was that I “really enjoy grocery shopping.” Recently, a friend named me maid of honor in her wedding; on the website for the event, she described me as “strongly opinionated and fiercely persistent.” Not wrong, but not what I want on my tombstone. I’ve always been bad at parties because the topics I bring up are too depressing, such as everything that’s wrong with my life, and everything that’s wrong with the world, and the futility of doing anything about either.

Neurotic people, twitchy and suspicious, can often “detect things that less sensitive people simply don’t register,” writes the personality psychologist Brian Little in Who Are You, Really? “This is not conducive to relaxed and easy living.” Rather than being motivated by rewards, neurotic people tend to fear risks and punishments; we ruminate on negative events more than emotionally stable people do. Many, like me, spend a lot of money on therapy and brain medications.

And while there’s nothing wrong with being an introvert, we tend to underestimate how much we’d enjoy behaving like extroverts. People have the most friends they will ever have at age 25 , and I am much older than that and never had very many friends to begin with. Besides, my editors wanted me to see if I could change my personality, and I’ll try anything once. (I’m open to experiences!) Maybe I, too, could become a friendly extrovert who doesn’t carry around emergency Xanax.

I gave myself three months.

The best-known expert on personality change is Brent Roberts, a psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Our interview in June felt, to me, a bit like visiting an evidence-based spiritual guru—he had a Zoom background of the red rocks of Sedona and the answers to all my big questions. Roberts has published dozens of studies showing that personality can change in many ways over time, challenging the notion that our traits are “set like plaster,” as the psychologist William James put it in 1887. But other psychologists still sometimes tell Roberts that they simply don’t believe it. There is a “deep-seated desire on the part of many people to think of personality as unchanging,” he told me. “It simplifies your world in a way that’s quite nice.” Because then you don’t have to take responsibility for what you’re like.

Don’t get too excited: Personality typically remains fairly stable throughout your life, especially in relation to other people. If you were the most outgoing of your friends in college, you will probably still be the bubbliest among them in your 30s. But our temperaments tend to shift naturally over the years. We change a bit during adolescence and a lot during our early 20s, and continue to evolve into late adulthood. Generally, people grow less neurotic and more agreeable and conscientious with age, a trend sometimes referred to as the “maturity principle.”

Longitudinal research suggests that careless, sullen teenagers can transform into gregarious seniors who are sticklers for the rules. One study of people born in Scotland in the mid-1930s—which admittedly had some methodological issues—found no correlation between participants’ conscientiousness at ages 14 and 77. A later study by Rodica Damian, a psychologist at the University of Houston, and her colleagues assessed the personalities of a group of American high-school students in 1960 and again 50 years later. They found that 98 percent of the participants had changed at least one personality trait.

Even our career interests are more stable than our personalities, though our jobs can also change us: In one study, people with stressful jobs became more introverted and neurotic within five years.

With a little work, you can nudge your personality in a more positive direction. Several studies have found that people can meaningfully change their personalities, sometimes within a few weeks , by behaving like the sort of person they want to be. Students who put more effort into their homework became more conscientious. In a 2017 meta-analysis of 207 studies, Roberts and others found that a month of therapy could reduce neuroticism by about half the amount it would typically decline over a person’s life. Even a change as minor as taking up puzzles can have an effect: One study found that senior citizens who played brain games and completed crossword and sudoku puzzles became more open to experiences. Though most personality-change studies have tracked people for only a few months or a year afterward, the changes seem to stick for at least that long.

When researchers ask, people typically say they want the success-oriented traits: to become more extroverted, more conscientious, and less neurotic. Roberts was surprised that I wanted to become more agreeable. Lots of people think they’re too agreeable, he told me. They feel they’ve become doormats.

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Roberts whether there’s anything he would change about his own personality. He admitted that he’s not always very detail-oriented (a.k.a. conscientious). He also regretted the anxiety (a.k.a. neuroticism) he experienced early in his career. Grad school was a “disconcerting experience,” he said: The son of a Marine and an artist, he felt that his classmates were all “brilliant and smart” and understood the world of academia better than he did.

I was struck by how similar his story sounded to my own. My parents are from the Soviet Union and barely understand my career in journalism. I went to crappy public schools and a little-known college. I’ve notched every minor career achievement through night sweats and meticulous emails and aching computer shoulders. Neuroticism had kept my inner fire burning, but now it was suffocating me with its smoke.

To begin my transformation, I called Nathan Hudson, a psychology professor at Southern Methodist University who created a tool to help people alter their personality. For a 2019 paper, Hudson and three other psychologists devised a list of “challenges” for students who wanted to change their traits. For, say, increased extroversion, a challenge would be to “introduce yourself to someone new.” Those who completed the challenges experienced changes in their personality over the course of the 15-week study, Hudson found. “Faking it until you make it seems to be a viable strategy for personality change,” he told me.

But before I could tinker with my personality, I needed to find out exactly what that personality consisted of. So I logged on to a website Hudson had created and took a personality test, answering dozens of questions about whether I liked poetry and parties, whether I acted “wild and crazy,” whether I worked hard. “I radiate joy” got a “strongly disagree.” I disagreed that “we should be tough on crime” and that I “try not to think about the needy.” I had to agree, but not strongly, that “I believe that I am better than others.”

I scored in the 23rd percentile on extroversion—“very low,” especially when it came to being friendly or cheerful. Meanwhile, I scored “very high” on conscientiousness and openness and “average” on agreeableness, my high level of sympathy for other people making up for my low level of trust in them. Finally, I came to the source of half my breakups, 90 percent of my therapy appointments, and most of my problems in general: neuroticism. I’m in the 94th percentile—“extremely high.”

I prescribed myself the same challenges that Hudson had given his students. To become more extroverted, I would meet new people. To decrease neuroticism, I would meditate often and make gratitude lists. To increase agreeableness, the challenges included sending supportive texts and cards, thinking more positively about people who frustrate me, and, regrettably, hugging. In addition to completing Hudson’s challenges, I decided to sign up for improv in hopes of increasing my extroversion and reducing my social anxiety. To cut down on how pissed off I am in general, and because I’m an overachiever, I also signed up for an anger-management class.

Read: Can personality be changed?

Hudson’s findings on the mutability of personality seem to endorse the ancient Buddhist idea of “no-self”—no core “you.” To believe otherwise, the sutras say, is a source of suffering. Similarly, Brian Little writes that people can have “multiple authenticities”—that you can sincerely be a different person in different situations. He proposes that people have the ability to temporarily act out of character by adopting “free traits,” often in the service of an important personal or professional project. If a shy introvert longs to schmooze the bosses at the office holiday party, they can grab a canapé and make the rounds. The more you do this, Little says, the easier it gets.

Staring at my test results, I told myself, This will be fun! After all, I had changed my personality before. In high school, I was shy, studious, and, for a while, deeply religious. In college, I was fun-loving and boy-crazy. Now I’m a basically hermetic “pressure addict,” as one former editor put it. It was time for yet another me to make her debut.

Ideally, in the end I would be happy, relaxed, personable. The screams of angry sources, the failure of my boyfriend to do the tiniest fucking thing—they would be nothing to me. I would finally understand what my therapist means when she says I should “just observe my thoughts and let them pass without judgment.” I made a list of the challenges and attached them to my nightstand, because I’m very conscientious.

Immediately I encountered a problem: I don’t like improv. It’s basically a Quaker meeting in which a bunch of office workers sit quietly in a circle until someone jumps up, points toward a corner of the room, and says, “I think I found my kangaroo!” My vibe is less “yes, and” and more “well, actually.” When I told my boyfriend what I was up to, he said, “You doing improv is like Larry David doing ice hockey.”

I was also scared out of my mind. I hate looking silly, and that’s all improv is. The first night, we met in someone’s townhouse in Washington, D.C., in a room that was, for no discernible reason, decorated with dozens of elephant sculptures. Right after the instructor said, “Let’s get started,” I began hoping that someone would grab one and knock me unconscious.

That didn’t happen, so instead I played a game called Zip Zap Zop, which involved making lots of eye contact while tossing around an imaginary ball of energy, with a software engineer, two lawyers, and a guy who works on Capitol Hill. Then we pretended to be traveling salespeople peddling sulfuric acid. If someone had walked in on us, they would have thought we were insane. And yet I didn’t hate it. I decided I could think of being funny and spontaneous as a kind of intellectual challenge. Still, when I got home, I unwound by drinking one of those single-serving wines meant for petite female alcoholics.

A few days later, I logged in to my first Zoom anger-management class. Christian Jarrett, a neuroscientist and the author of Be Who You Want , writes that spending quality time with people who are dissimilar to you increases agreeableness. And the people in my anger-management class did seem pretty different from me. Among other things, I was the only person who wasn’t court-ordered to be there.

We took turns sharing how anger has affected our lives. I said it makes my relationship worse—less like a romantic partnership and more like a toxic workplace. Other people worried that their anger was hurting their family. One guy shared that he didn’t understand why we were talking about our feelings when kids in China and Russia were learning to make weapons, which I deemed an interesting point, because you’re not allowed to criticize others in anger management.

The sessions—I went to six—mostly involved reading worksheets together, which was tedious, but I did learn a few things. Anger is driven by expectations. If you think you’re going to be in an anger-inducing situation, one instructor said, try drinking a cold can of Coke, which may stimulate your vagus nerve and calm you down. A few weeks in, I had a rough day, my boyfriend gave me some stupid suggestions, and I yelled at him. Then he said I’m just like my dad, which made me yell more. When I shared this in anger management, the instructors said I should be clearer about what I need from him when I’m in a bad mood—which is listening, not advice.

All the while, I had been working on my neuroticism, which involved making a lot of gratitude lists. Sometimes it came naturally. As I drove around my little town one morning, I thought about how grateful I was for my boyfriend, and how lonely I had been before I met him, even in other relationships. Is this gratitude? I wondered. Am I doing it?

What is personality, anyway, and where does it come from?

Contrary to conventional wisdom about bossy firstborns and peacemaking middles, birth order doesn’t influence personality . Nor do our parents shape us like lumps of clay. If they did, siblings would have similar dispositions, when they often have no more in common than strangers chosen off the street. Our friends do influence us, though, so one way to become more extroverted is to befriend some extroverts. Your life circumstances also have an effect: Getting rich can make you less agreeable, but so can growing up poor with high levels of lead exposure.

A common estimate is that about 30 to 50 percent of the differences between two people’s personalities are attributable to their genes. But just because something is genetic doesn’t mean it’s permanent. Those genes interact with one another in ways that can change how they behave, says Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. They also interact with your environment in ways that can change how you behave. For example: Happy people smile more, so people react more positively to them, which makes them even more agreeable. Open-minded adventure seekers are more likely to go to college, where they grow even more open-minded.

Harden told me about an experiment in which mice that were genetically similar and reared in the same conditions were moved into a big cage where they could play with one another. Over time, these very similar mice developed dramatically different personalities. Some became fearful, others sociable and dominant. Living in Mouseville, the mice carved out their own ways of being, and people do that too. “We can think of personality as a learning process,” Harden said. “We learn to be people who interact with our social environments in a certain way.”

This more fluid understanding of personality is a departure from earlier theories. A 1914 best seller called The Eugenic Marriage (which is exactly as offensive as it sounds) argued that it is not possible to change a child’s personality “one particle after conception takes place.” In the 1920s, the psychoanalyst Carl Jung posited that the world consists of different “types” of people—thinkers and feelers, introverts and extroverts. (Even Jung cautioned, though, that “there is no such thing as a pure extravert or a pure introvert. Such a man would be in the lunatic asylum.”) Jung’s rubric captured the attention of a mother-daughter duo, Katharine Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers, neither of whom had any formal scientific training. As Merve Emre describes in The Personality Brokers , the pair seized on Jung’s ideas to develop that staple of Career Day, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. But the test is virtually meaningless . Most people aren’t ENTJs or ISFPs; they fall between categories.

Over the years, poor parenting has been a popular scapegoat for bad personalities. Alfred Adler, a prominent turn-of-the-20th-century psychologist, blamed mothers, writing that “wherever the mother-child relationship is unsatisfactory, we usually find certain social defects in the children.” A few scholars attributed the rise of Nazism to strict German parenting that produced hateful people who worshipped power and authority. But maybe any nation could have embraced a Hitler: It turns out that the average personalities of different countries are fairly similar. Still, the belief that parents are to blame persists, so much so that Roberts closes the course he teaches at the University of Illinois by asking students to forgive their moms and dads for whatever personality traits they believe were instilled or inherited.

Not until the 1950s did researchers acknowledge people’s versatility—that we can reveal new faces and bury others. “Everyone is always and everywhere, more or less consciously, playing a role,” the sociologist Robert Ezra Park wrote in 1950. “It is in these roles that we know each other; it is in these roles that we know ourselves.”

Around this time, a psychologist named George Kelly began prescribing specific “roles” for his patients to play. Awkward wallflowers might go socialize in nightclubs, for example. Kelly’s was a rhapsodic view of change; at one point he wrote that “all of us would be better off if we set out to be something other than what we are.” Judging by the reams of self-help literature published each year, this is one of the few philosophies all Americans can get behind.

About six weeks in, my adventures in extroversion were going better than I’d anticipated. Intent on talking to strangers at my friend’s wedding, I approached a group of women and told them the story of how my boyfriend and I had met—I moved into his former room in a group house—which they deemed the “story of the night.” On the winds of that success, I tried to talk to more strangers, but soon encountered the common wedding problem of Too Drunk to Talk to People Who Don’t Know Me.

For more advice on becoming an extrovert, I reached out to Jessica Pan, a writer in London and the author of the book Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come . Pan was an extreme introvert, someone who would walk into parties and immediately walk out again. At the start of the book, she resolved to become an extrovert. She ran up to strangers and asked them embarrassing questions. She did improv and stand-up comedy. She went to Budapest and made a friend. Folks, she networked.

In the process, Pan “flung open the doors” to her life, she writes. “Having the ability to morph, to change, to try on free traits, to expand or contract at will, offers me an incredible feeling of freedom and a source of hope.” Pan told me that she didn’t quite become a hard-core extrovert, but that she would now describe herself as a “gregarious introvert.” She still craves alone time, but she’s more willing to talk to strangers and give speeches. “I will be anxious, but I can do it,” she said.

I asked her for advice on making new friends, and she told me something a “friendship mentor” once told her: “Make the first move, and make the second move, too.” That means you sometimes have to ask a friend target out twice in a row—a strategy I had thought was gauche.

I practiced by trying to befriend some female journalists I admired but had been too intimidated to get to know. I messaged someone who seemed cool based on her writing, and we arranged a casual beers thing. But on the night we were supposed to get together, her power went out, trapping her car in her garage.

Instead, I caught up with an old friend by phone, and we had one of those conversations you can have only with someone you’ve known for years, about how the people who are the worst remain the worst, and how all of your issues remain intractable, but good on you for sticking with it. By the end of our talk, I was high on agreeable feelings. “Love you, bye!” I said as I hung up.

“LOL,” she texted. “Did you mean to say ‘I love you’?”

Who was this new Olga?

For my gratitude journaling, I purchased a notebook whose cover said, “Gimme those bright sunshiney vibes.” I soon noticed, though, that my gratitude lists were repetitive odes to creature comforts and entertainment: Netflix, yoga, TikTok, leggings, wine. After I cut my finger cooking, I expressed gratitude for the dictation software that let me write without using my hands, but then my finger healed. “Very hard to come up with new things to say,” I wrote one day.

I find expressing gratitude unnatural, because Russians believe doing so will provoke the evil eye; our God doesn’t like too much bragging. The writer Gretchen Rubin hit a similar wall when keeping a gratitude journal for her book The Happiness Project . “It had started to feel forced and affected,” she wrote, making her annoyed rather than grateful.

I was also supposed to be meditating, but I couldn’t. On almost every page, my journal reads, “Meditating sucks!” I tried a guided meditation that involved breathing with a heavy book on my stomach—I chose Nabokov’s Letters to Véra —only to find that it’s really hard to breathe with a heavy book on your stomach.

I tweeted about my meditation failures, and Dan Harris, a former Good Morning America weekend anchor, replied: “The fact that you’re noticing the thoughts/obsessions is proof that you are doing it correctly!” I picked up Harris’s book 10% Happier , which chronicles his journey from a high-strung reporter who had a panic attack on air to a high-strung reporter who meditates a lot. At one point, he was meditating for two hours a day.

When I called Harris, he said that it’s normal for meditation to feel like “training your mind to not be a pack of wild squirrels all the time.” Very few people actually clear their minds when they’re meditating. The point is to focus on your breath for however long you can—even if it’s just a second—before you get distracted. Then do it over and over again. Occasionally, when Harris meditates, he still “rehearses some grand, expletive-filled speech I’m gonna deliver to someone who’s wronged me.” But now he can return to his breath more quickly, or just laugh off the obsessing.

Harris suggested that I try loving-kindness meditation, in which you beam affectionate thoughts toward yourself and others. This, he said, “sets off what I call a gooey upward spiral where, as your inner weather gets balmier, your relationships get better.” In his book, Harris describes meditating on his 2-year-old niece. As he thought about her “little feet” and “sweet face with her mischievous eyes,” he started crying uncontrollably.

What a pussy , I thought.

I downloaded Harris’s meditation app and pulled up a loving-kindness session by the meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg. She had me repeat calming phrases like “May you be safe” and “May you live with ease.” Then she asked me to envision myself surrounded by a circle of people who love me, radiating kindness toward me. I pictured my family, my boyfriend, my friends, my former professors, emitting beneficence from their bellies like Care Bears. “You’re good; you’re okay,” I imagined them saying. Before I knew what was happening, I had broken into sobs.

After two brutal years, people may be wondering if surviving a pandemic has at least improved their personality, making them kinder and less likely to sweat the small stuff. “Post-traumatic growth,” or the idea that stressful events can make us better people, is the subject of one particularly cheery branch of psychology. Some big events do seem to transform personality: People grow more conscientious when they start a job they like, and they become less neurotic when they enter a romantic relationship. But in general, it’s not the event that changes your personality; it’s the way you experience it. And the evidence that people grow as a result of difficulty is mixed. Studies of post-traumatic growth are tainted by the fact that people like to say they got something out of their trauma.

It’s a nice thing to believe about yourself—that, pummeled by misfortune, you’ve emerged stronger than ever. But these studies are mostly finding that people prefer to look on the bright side.

Read: The opposite of toxic positivity

In more rigorous studies, evidence of a transformative effect fades. Damian, the University of Houston psychologist, gave hundreds of students at the university a personality test a few months after Hurricane Harvey hit, in November 2017, and repeated the test a year later. The hurricane was devastating: Many students had to leave their homes; others lacked food, water, or medical care for weeks. Damian found that her participants hadn’t grown, and they hadn’t shriveled. Overall they stayed the same. Other research shows that difficult times prompt us to fall back on tried-and-true behaviors and traits, not experiment with new ones.

Growth is also a strange thing to ask of the traumatized. It’s like turning to a wounded person and demanding, “Well, why didn’t you grow, you lazy son of a bitch?” Roberts said. Just surviving should be enough.

It may be impossible to know how the pandemic will change us on average, because there is no “average.” Some people have struggled to keep their jobs while caring for children; some have lost their jobs; some have lost loved ones. Others have sat at home and ordered takeout. The pandemic probably hasn’t changed you if the pandemic itself hasn’t felt like that much of a change.

I blew off anger management one week to go see Kesha in concert. I justified it because the concert was a group activity, plus she makes me happy. The next time the class gathered, we talked about forgiveness, which Child Weapons Guy was not big on. He said that rather than forgive his enemies, he wanted to invite them onto a bridge and light the bridge on fire. I thought he should get credit for being honest—who hasn’t wanted to light all their enemies on fire?—but the anger-management instructors started to look a little angry themselves.

In the next session, Child Weapons Guy seemed contrite, saying he realized that he uses his anger to deal with life, which was a bigger breakthrough than anyone expected. I was also praised, for an unusually tranquil trip home to see my parents, which my instructors said was an example of good “expectation management.”

Meanwhile, my social life was slowly blooming. A Twitter acquaintance invited me and a few other strangers to a whiskey tasting, and I said yes even though I don’t like whiskey or strangers. At the bar, I made some normal-person small talk before having two sips of alcohol and wheeling the conversation around to my personal topic of interest: whether I should have a baby. The woman who organized the tasting, a self-proclaimed extrovert, said people are always grateful to her for getting everyone to socialize. At first, no one wants to come, but people are always happy they did.

I thought perhaps whiskey could be my “thing,” and, to tick off another challenge from Hudson’s list, decided to go to a whiskey bar on my own one night and talk to strangers. I bravely steered my Toyota to a sad little mixed-use development and pulled up a stool at the bar. I asked the bartender how long it had taken him to memorize all the whiskeys on the menu. “Two months,” he said, and turned back to peeling oranges. I asked the woman sitting next to me how she liked her appetizer. “It’s good!” she said. This is awful! I thought. I texted my boyfriend to come meet me.

The larger threat on my horizon was the improv showcase—a free performance for friends and family and whoever happened to jog past Picnic Grove No. 1 in Rock Creek Park. The night before, I kept jolting awake from intense, improv-themed nightmares. I spent the day grimly watching old Upright Citizens Brigade shows on YouTube. “I’m nervous on your behalf,” my boyfriend said when he saw me clutching a throw pillow like a life preserver.

From the January/February 2014 issue: Surviving anxiety

To describe an improv show is to unnecessarily punish the reader, but it went fairly well. Along with crushing anxiety, my brain courses with an immigrant kid’s overwhelming desire to do whatever people want in exchange for their approval. I improvised like they were giving out good SAT scores at the end. On the drive home, my boyfriend said, “Now that I’ve seen you do it, I don’t really know why I thought it’s something you wouldn’t do.”

I didn’t know either. I vaguely remembered past boyfriends telling me that I’m insecure, that I’m not funny. But why had I been trying to prove them right? Surviving improv made me feel like I could survive anything, as bratty as that must sound to all my ancestors who survived the siege of Leningrad.

Finally, the day came to retest my personality and see how much I’d changed. I thought I felt hints of a mild metamorphosis. I was meditating regularly, and had had several enjoyable get-togethers with people I wanted to befriend. And because I was writing them down, I had to admit that positive things did, in fact, happen to me.

But I wanted hard data. This time, the test told me that my extroversion had increased, going from the 23rd percentile to the 33rd. My neuroticism decreased from “extremely high” to merely “very high,” dropping to the 77th percentile. And my agreeableness score … well, it dropped, from “about average” to “low.”

I told Brian Little how I’d done. He said I likely did experience a “modest shift” in extroversion and neuroticism, but also that I might have simply triggered positive feedback loops. I got out more, so I enjoyed more things, so I went to more things, and so forth.

Why didn’t I become more agreeable, though? I had spent months dwelling on the goodness of people, devoted hours to anger management, and even sent an e-card to my mom. Little speculated that maybe by behaving so differently, I had heightened my internal sense that people aren’t to be trusted. Or I might have subconsciously bucked against all the syrupy gratitude time. That I had tried so hard and made negative progress—“I think it’s a bit of a hoot,” he said.

Perhaps it’s a relief that I’m not a completely new person. Little says that engaging in “free trait” behavior—acting outside your nature—for too long can be harmful, because you can start to feel like you are suppressing your true self. You end up feeling burned out or cynical.

The key may not be in swinging permanently to the other side of the personality scale, but in balancing between extremes, or in adjusting your personality depending on the situation. “The thing that makes a personality trait maladaptive is not being high or low on something; it’s more like rigidity across situations,” Harden, the behavioral geneticist, told me.

“So it’s okay to be a little bitchy in your heart, as long as you can turn it off?” I asked her.

“People who say they’re never bitchy in their heart are lying,” she said.

Susan Cain, the author of Quiet and the world’s most famous introvert, seems reluctant to endorse the idea that introverts should try to be more outgoing. Over the phone, she wondered why I wanted to be more extroverted in the first place. Society often urges people to conform to the qualities extolled in performance reviews—punctual, chipper, gregarious. But there are upsides to being introspective, skeptical, and even a little neurotic. She said it’s possible that I didn’t change my underlying introversion, that I just acquired new skills. She thought I could probably maintain this new personality, so long as I kept doing the tasks that got me here.

Hudson cautioned that personality scores can bounce around a bit from moment to moment; to be certain of my results, I ideally would have taken the test a number of times. Still, I felt sure that some change had taken place. A few weeks later, I wrote an article that made people on Twitter really mad. This happens to me once or twice a year, and I usually suffer a minor internal apocalypse. I fight the people on Twitter while crying, call my editor while crying, and Google How to become an actuary while crying. This time, I was stressed and angry, but I just waited it out.

This kind of modest improvement, I realized, is the goal of so much self-help material. Hours a day of meditation made Harris only 10 percent happier. My therapist is always suggesting ways for me to “go from a 10 to a nine on anxiety.” Some antidepressants make people feel only slightly less depressed, yet they take the drugs for years. Perhaps the real weakness of the “change your personality” proposition is that it implies incremental change isn’t real change. But being slightly different is still being different—the same you but with better armor.

The late psychologist Carl Rogers once wrote, “When I accept myself just as I am, then I can change,” and this is roughly where I’ve landed. Maybe I’m just an anxious little introvert who makes an effort to be less so. I can learn to meditate; I can talk to strangers; I can be the mouse who frolics through Mouseville, even if I never become the alpha. I learned to play the role of a calm, extroverted softy, and in doing so I got to know myself.

This article appears in the March 2022 print edition with the headline “My Personality Transplant.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

About the Author

More Stories

The Weak Science Behind Psychedelics

The Friendship Paradox

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Can You Change Your Personality?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Factors That Shape Personality

- "In-Betweens" of Personality

Beliefs and Self-Beliefs

How to change your personality.

The desire to alter personality is not uncommon. Shy people might wish they were more outgoing and talkative. Hot-tempered individuals might wish they could keep their cool in emotionally charged situations.

Is it possible to change your personality or are our basic personality patterns fixed throughout life? While self-help books and websites often tout plans you can follow to change your habits and behaviors, there is a persistent belief that our underlying personalities are impervious to change.

The Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud suggested that personality was largely set in stone by the tender age of 5. Even many modern psychologists suggest that overall personality is relatively fixed and stable throughout life.

But what if you want to change your personality? Can the right approach and hard work lead to real personality change, or are we stuck with undesirable traits that hold us back from achieving our goals?

To understand whether personality can be changed, we must first understand what exactly causes personality. The age-old nature versus nurture debate once again comes into play. Is personality shaped by our genetics (nature) or by our upbringing, experiences , and environment (nurture)?

In the past, theorists and philosophers often took a one-versus-the-other approach and advocated either for the importance of nature or nurture, but today most thinkers would agree that it is a mixture of the two forces that ultimately shape our personalities.

Not only that, but the constant interaction between genetics and the environment can help shape how personality is expressed. For example, you might be genetically predisposed to being friendly and laid back, but working in a high-stress environment might lead you to be more short-tempered and uptight than you might be in a different setting.

Dweck relates a story of identical twin boys separated after birth and reared apart. As adults, the two men married women with the same first names, shared similar hobbies, and had similar levels of certain traits measured on personality assessments.

It is such examples that provide the basis for the idea that our personalities are largely out of our control. Instead of being shaped by our environment and unique experiences, these twin studies point to the power of genetic influences.

Genetics is certainly important, but other studies also demonstrate that our upbringing and even our culture interact with our genetic blueprints to shape who we are.

What Are Your Dominant Traits? Take the Free Test

Our fast and free personality test can help give you an idea of your dominant personality traits and how they may influence your behaviors.

"In-Between" Qualities of Personality

Some experts, including psychologist Carol Dweck, believe that changing the behavior patterns , habits, and beliefs that lie under the surface of the broad personality traits (e.g., introversion , agreeableness) is the real key to personality change.

Broad traits might be stable through life, but Dweck believes that it is our "in-between" qualities that lie under the surface of the broad traits that are the most important in making us who we are. It is those in-between qualities, she believes, that can be changed.

"In-between" qualities that we can potentially change, thereby also changing our personality include:

- Beliefs and belief systems . While changing certain aspects of your personality might be challenging, you can realistically tackle changing some of the underlying beliefs that help shape and control how your personality is expressed.

- Goals and coping strategies . For example, while you might have more of a Type A personality , you can learn new coping skills and stress management techniques that help you become a more relaxed person.

While changing beliefs might not necessarily be easy, it offers a good starting point. Our beliefs shape so much of our lives, from how we view ourselves and others, how we function in daily life, how we deal with life's challenges, and how we forge connections with other people.

If we can create real change in our beliefs, it is something that might have a resounding effect on our behaviors and possibly on certain aspects of our personalities.

"People's beliefs include their mental representations of the nature and workings of the self, of their relationships, and of their world. From infancy, humans develop these beliefs and representations, and many prominent personality theorists of different persuasions acknowledge that they are a fundamental part of personality," Dweck explained in a 2008 paper.

Take, for example, beliefs about the self, including whether personal attributes and characteristics are fixed or malleable. If you believe your intelligence is at a fixed level, then you are not likely to take steps to deepen your thinking. If, however, you view such characteristics as changeable, you will likely make a greater effort to challenge yourself and broaden your mind.

Obviously, beliefs about the self do play a critical role in how people function, but researchers have found that people can change their beliefs in order to take a more malleable approach to self-attributes.

In one experiment, students had a greater appreciation of academics, higher grade point averages, and greater overall enjoyment of school after discovering that the brain continues to form new connections in response to new knowledge.

Dweck's own research has demonstrated that how kids are praised can have an impact on their self-beliefs. Those who are praised for their intelligence tend to hold fixed-theory beliefs about their own personal attributes. These kids view their intelligence as an unchangeable trait; you either have it or you don't.

Children who are praised for their efforts , on the other hand, typically view their intelligence as malleable. These kids, Dweck has found, tend to persist in the face of difficulty and are more eager to learn.

At many points in your life, you may find that there are certain aspects of your personality that you wish you could change. You might even set goals and work toward tackling those potentially problematic traits. For example, it is common to set New Year's Resolutions focused on changing parts of your personality such as becoming more generous, kind, patient, or outgoing.

In general, many experts agree that making real and lasting changes to broad traits can be exceedingly difficult. So, if you are dissatisfied with certain aspects of your personality, is there really anything you can do to change them?

Changing from an introvert to an extravert might be extremely difficult (or even impossible), but there are things that the experts believe you can do to make real and lasting changes to aspects of your personality. Here's how to change your personality if you want to be a better person.

Learn New Habits

Psychologists have found that people who exhibit positive personality traits (such as kindness and honesty) have developed habitual responses that have stuck. Habit can be learned, so changing your habitual responses over time is one way to create personality change.

Of course, forming a new habit or breaking an old one is never easy and it takes time and serious effort. With enough practice, these new patterns of behavior will eventually become second nature.

Challenge Your Self-Beliefs

If you believe you cannot change, then you will not change. If you are trying to become more outgoing, but you believe that your introversion is a fixed, permanent, and unchangeable trait, then you will simply never try to become more sociable. But if you believe that your personal attributes are changeable, you are more likely to make an effort to become more gregarious.

Focus on Your Efforts

Dweck's research has consistently shown that praising efforts rather than ability is essential. Instead of thinking "I'm so smart" or "I'm so talented," replace such phrases with "I worked really hard" or "I found a good way of solving that problem."

By shifting to more of a growth mindset rather than a fixed mindset, you may find that it is easier to experience real change and growth.

Act the Part

Positive psychologist Christopher Peterson realized early on that his introverted personality might have a detrimental impact on his career as an academic. To overcome this, he decided to start acting extroverted in situations that called for it, like when delivering a lecture to a class full of students or giving a presentation at a conference.

Eventually, these behaviors simply become second nature. While he suggested that he was still an introvert, he learned how to become extroverted when he needed to be.

A Word From Verywell

Personality change might not be easy, and changing some broad traits might never really be fully possible. But researchers do believe that there are things you can do to change certain parts of your personality, the aspects that exist beneath the level of those broad traits, that can result in real changes to the way you act, think, and function in your day-to-day life.

Frank G. Freud's concept of the superego: review and assessment . Psychoanal Psychol. 1999;16(3):448–463. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.16.3.448

Mõttus R, Johnson W, Deary IJ. Personality traits in old age: Measurement and rank-order stability and some mean-level change . Psychol Aging. 2012;27 (1):243–249. doi:10.1037/a0023690

Johnson W, Turkheimer E, Gottesman II, Bouchard TJ Jr. Beyond heritability: Twin studies in behavioral research . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2010;18(4):217–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x

Dweck CS. Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2008;17(6):391-394. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00612.x

Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping . Annu Rev Psychol . 2010;61:679–704. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Doménech-Betoret F, Abellán-Roselló L, Gómez-Artiga A. Self-efficacy, satisfaction, and academic achievement: The mediator role of students' expectancy-value beliefs . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1193. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01193

Mueller CM, Dweck CS. Praise for intelligence can undermine children's motivation and performance . J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75 (1):33–52. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

Wood W. Habit in personality and social psychology . Pers Soc Psychol Rev . 2017;21(4):389–403. doi:10.1177/1088868317720362

Psychology Today. Second nature .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Personality Can Change Over A Lifetime, And Usually For The Better

Christopher Soto

Why do people act the way they do? Many of us intuitively gravitate toward explaining human behavior in terms of personality traits: characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving that tend to be stable over time and consistent across situations.

This intuition has been a topic of fierce scientific debate since the 1960s, with some psychologists arguing that situations — not traits — are the most important causes of behavior. Some have even argued that personality traits are figments of our imagination that don't exist at all.

But in the past two decades, a large and still-growing body of research has established that personality traits are very much real , and that how people describe someone's personality accurately predicts that person's actual behavior .

The effects of personality traits on behavior are easiest to see when people are observed repeatedly across a variety of situations. On any one occasion, a person's behavior is influenced by both their personality and the situation, as well as other factors such as their current thoughts, feelings and goals. But when someone is observed in many different situations, the influence of personality on behavior is hard to miss. For example, you probably know some people who consistently (but not always) show up on time, and others who consistently run late.

We've also gained a clear sense of which personality traits are most generally useful for understanding behavior. The world's languages include many thousands of words for describing personality, but most of these can be organized in terms of the "Big Five" trait dimensions : extraversion (characterized by adjectives like outgoing, assertive and energetic vs. quiet and reserved); agreeableness (compassionate, respectful and trusting vs. uncaring and argumentative); conscientiousness (orderly, hard-working and responsible vs. disorganized and distractible); negative emotionality (prone to worry, sadness and mood swings vs. calm and emotionally resilient); and open-mindedness (intellectually curious, artistic and imaginative vs. disinterested in art, beauty and abstract ideas).

The Personality Myth

We like to think of our own personalities, and those of our family and friends, as predictable, constant over time. But what if they aren't? Explore that question in the latest episode of the NPR podcast and show Invisibilia .

And while personality traits are relatively stable over time , they can and often do gradually change across the life span. What's more, those changes are usually for the better . Many studies , including some of my own, show that most adults become more agreeable, conscientious and emotionally resilient as they age. But these changes tend to unfold across years or decades, rather than days or weeks. Sudden, dramatic changes in personality are rare.

Due to their effects on behavior and continuity over time, personality traits help shape the course of people's lives. When measured using scientifically constructed and validated personality tests, like one that Oliver John and I recently developed, the Big Five traits predict a long list of consequential life outcomes: performance in school and at work, relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners, life satisfaction and emotional well-being, physical health and longevity, and many more. Of course, none of these outcomes are entirely determined by personality; all of them are also influenced by people's life circumstances. But personality traits clearly influence people's lives in important ways and help explain why two people in similar circumstances often end up with different outcomes.

Consider one of life's most important and potentially difficult decisions: who (if anyone!) to choose as your mate. The research evidence indicates that personality should play a role in this decision. Studies following couples over time have consistently found that choosing a spouse who is kind, responsible and emotionally resilient will substantially improve your chances of maintaining a stable and satisfying marriage. In fact, personality traits are some of the most powerful predictors of long-term relationship quality.

This is not to say that we've already figured out everything there is to know about personality traits.

Shots - Health News

Invisibilia: is your personality fixed, or can you change who you are.

For example, we know that personality change can happen, that it usually happens gradually, and that it's usually for the better. But we don't fully understand the causes of personality change just yet.

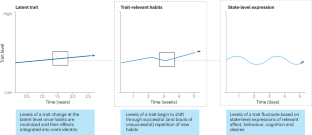

Research by Brent Roberts, Joshua Jackson, Wiebke Bleidorn and others highlights the importance of social roles . When we invest in a role that calls for particular kinds of behavior, such as a job that calls for being hard-working and responsible, then over time those behaviors tend to become integrated into our personality.

A 2015 study by Nathan Hudson and Chris Fraley indicates that some people may even be able to intentionally change their own personality through sustained personal effort and careful goal-setting. A study of mine published last year, and another by Jule Specht, suggest that positive personality changes accelerate when people are leading meaningful and satisfying lives.

So although we now know a lot more about personality than we did even a few years ago, we certainly don't know everything. The nature, development and consequences of personality traits remain hot topics of research, and we're learning new things all the time. Stay tuned.

Christopher Soto is an associate professor of psychology at Colby College and a member of the executive board of the Association for Research in Personality . Follow him on Twitter @cjsotomatic.

- personality

- behavioral psychology

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Personality change across the lifespan: Insights from a cross-cultural longitudinal study

William j chopik, shinobu kitayama.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence concerning this manuscript should be addressed to William J. Chopik, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, 316 Physics Rd., East Lansing, Michigan 48824. [email protected]

Michigan State University

University of Michigan

Issue date 2018 Jun.

Personality traits are characterized by both stability and change across the lifespan. Many of the mechanisms hypothesized to cause personality change (e.g., the timing of various social roles, physical health, and cultural values) differ considerably across culture. Moreover, personality consistency is valued highly in Western societies, but less so in non-Western societies. Few studies have examined how personality changes differently across cultures.

We employed a multi-level modeling approach to examine age-related changes in Big Five personality traits in two large panel studies of Americans (n = 6,259; M age = 46.85; 52.5% Female) and Japanese (n = 1,021; M age = 54.28; 50.9% Female). Participants filled out personality measures twice, over either a 9-year interval (for Americans) or a 4-year period (for Japanese).

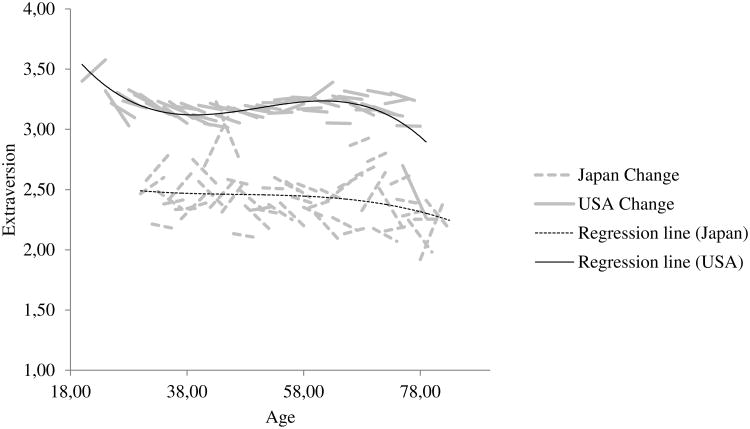

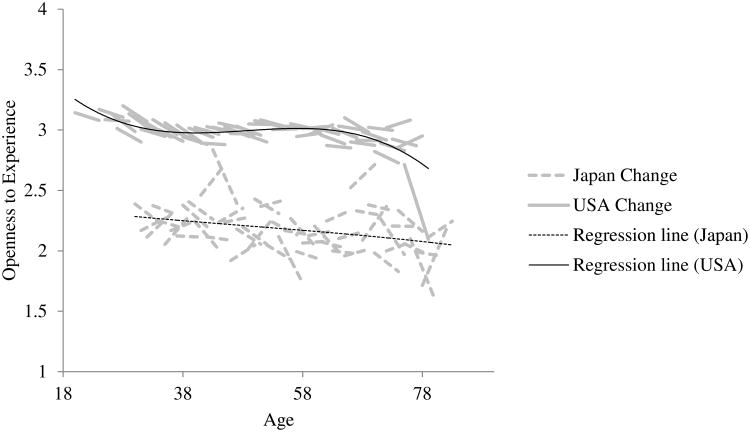

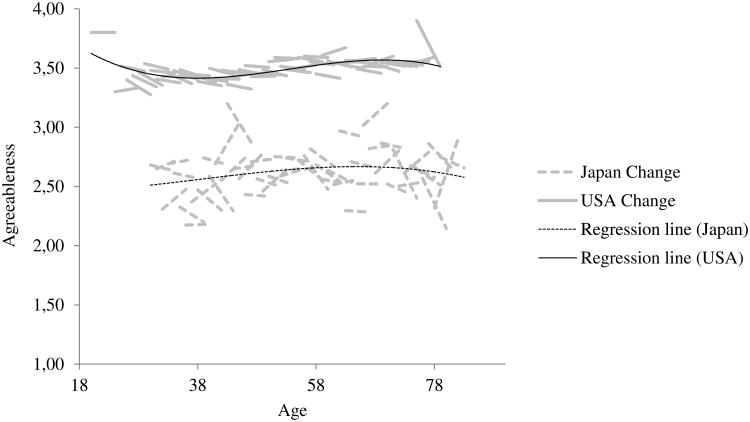

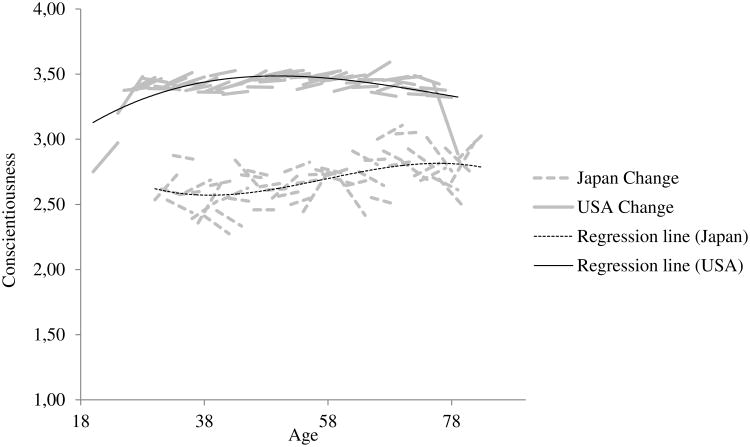

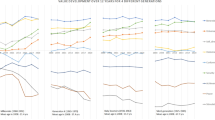

Changes in agreeableness and openness to experience did not systematically vary across cultures; changes in extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness did vary across cultures. Further, Japanese show significantly greater fluctuation in the level of all of the traits tested over time than Americans.

Conclusions

The culture-specific social, ecological, and life-course factors that are associated with personality change are discussed.

Keywords: Big Five personality, lifespan development, culture, MIDUS, MIDJA

Researchers have assumed that personality traits are characterized by both stability and change across the lifespan. The primary interpretation of age-related changes in personality is that our personalities change in response to the social roles and responsibilities that we adopt over time ( Roberts, Wood, & Smith, 2005 ). For example, people become more agreeable and conscientious when they invest more in their occupation and less so when they retire ( Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011 ). People also become more introverted following marriage ( Specht et al., 2011 ). Military personnel decrease in agreeableness following military training ( Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Ludtke, & Trautwein, 2012 ). A meta-analysis showed that many personality changes result from the degree to which people invest in social roles in work, family, religion, and volunteering ( Lodi-Smith & Roberts, 2007 ). However, social roles, expectations, and the timing of these events often differ by culture, so the degree to which personality changes may differ accordingly across different cultures and social settings. In the current study, we examined life-course changes in personality from longitudinal data obtained from the United States and Japan. With this analysis, we examined life-course trajectories of different personality traits and how these trajectories might differ between the United States and Japan.

There is a strong consensus among personality psychologists that five broad domains characterize much of human variation in personality ( John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008 ). These five broad, global traits—often referred to as the Big Five—are extraversion (traits like outgoing and lively ), agreeableness (traits like helpful and sympathetic ), neuroticism (traits like moody and worrying ), conscientiousness (traits like hardworking and responsible ), and openness to experience (traits like imaginative and curious ). Examining how these five traits differ across the lifespan has been the subject of many previous studies, both cross-sectionally (e.g., Soto, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2010 ; Srivastava, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2003 ) and longitudinally (e.g., Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006 ; Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005 ). The preponderance of evidence from these studies shows that neuroticism, extraversion, and openness to experience tend to decline across the lifespan. Agreeableness tends to increase across the lifespan. Conscientiousness often has a curvilinear association with age, such that people become more conscientiousness until about middle age before declining in late life ( Lucas & Donnellan, 2011 ; Terracciano et al., 2005 ). This late life decline is hypothesized to coincide with rapid declines in health and cognitive ability ( Wagner, Ram, Smith, & Gerstorf, 2015 ).

Will such life course trajectories of personality vary across different cultures? Some researchers have suggested that personality development is relatively similar or universal across cultures, reflecting changes not in environmental circumstances, but rather in intrinsic, biological systems across life that are present in all cultures ( McCrae, 2004 ; McCrae et al., 1999 ; McCrae et al., 2000 ). Moreover, even if personality is not fully determined by intrinsic, biological factors, life course trajectories of personality could be similar across cultures if many of the social roles hypothesized to cause adult personality development are present in most cultures ( Roberts et al., 2005 ). Unlike the biological review, however, the latter social role view implies that there should be substantial cross-cultural variability in personality change to the extent that the timing of family-, education-, and employment-related transitions is cross-culturally variable ( Bleidorn et al., 2013 ).

Previous cross-cultural studies show similar age differences in cultures such as Belgium, Russia, China, the Czech Republic and several more ( Bleidorn et al., 2013 ; McCrae et al., 2004 ; McCrae et al., 2002 ; McCrae & Terracciano, 2005 ) whereas others have found considerable age-related personality changes and differences across cultures ( Donnellan & Lucas, 2008 ; Lucas & Donnellan, 2009 ; Wortman, Lucas, & Donnellan, 2012 ), even among cultures that are relatively similar (e.g., Britain, Germany, and Australia). One important caveat is that many of these studies are cross-sectional in design. Among the few longitudinal studies conducted, they are exclusively focused on personality change in Western cultures ( Lucas & Donnellan, 2011 ; Wortman et al., 2012 ). With cross-sectional designs, it is impossible to dissociate true personality change from birth cohort effects ( McCrae et al., 1999 ; McCrae et al., 2000 ). In fact, this consideration is often used to explain why studies of age differences across cultures sometimes yield contradictory findings ( Donnellan & Lucas, 2008 ). With respect to how personality changes over time in non-Western cultures, little data currently exists to examine this question. How does personality change differ among two relatively dissimilar countries, like the United States and Japan? To make progress in this area, it is crucial to have cross-cultural, longitudinal data that cover a wide age range.

Beyond investment and timing in social roles, which have some similarities across cultures, there are at least two important classes of considerations that are relevant to life-course changes in personality. First, cultural variation in physical health may have consequences on the life-course trajectory of personality. Longevity varies dramatically across cultures. Among modern industrialized societies, Japan enjoys the highest longevity in the world ( Miyagi, Iwama, Kawabata, & Hasegawa, 2003 ), whereas Americans fare far worse ( Benfante, 1992 ). Much of this difference may be explained by physical health. A recent study using markers of inflammation (interleukin-6 and c-reactive protein) and cardiovascular functioning (systolic blood pressure and heart rate) to assess biological health risk and found that, across a wide age span, Japanese adults are at a substantially lower biological health risk than Americans ( Coe et al., 2011 ). Health may also prove to be relevant in understanding age-linked changes in personality traits. Two important considerations may follow from this analysis.

To begin, as people age, there may be a decline of physical ability—severely limiting their ability to go out and explore new social relationships or new knowledge ( Jokela, Hakulinen, Singh-Manoux, & Kivimaki, 2014 ; Wagner et al., 2015 ). Thus, older adults may be less extraverted and less open to new experiences due to health limitations. Support for this possibility can be found in an explanation for the origins of cultural variation in personality from an evolutionary perspective. For example, people living in countries with high disease prevalence rates may be less extraverted and open because their local ecologies shape their interpersonal behavior and social institutions ( Schaller & Murray, 2008 ). However, this decline in extraversion and openness to experience may be buffered if Japanese adults are healthier over longer stretches of time. Moreover, older people may prioritize social emotional goals of “feeling good” over more task-relevant and information-related goals ( Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999 ), leading them to be both less neurotic and more agreeable. Further, evidence that individuals become less anxious and emotionally mature as they age would also lead to the prediction that neuroticism declines and agreeableness increases ( Gross et al., 1997 ; Srivastava et al., 2003 ). However, insofar as some degree of good health is required to pursue such goals ( Charles & Luong, 2013 ; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004 ), both decreases of neuroticism and increases of agreeableness may be more pronounced among healthy populations, namely, among Japanese as compared to Americans.

Second, cultural variation in values may have important consequences on the life-course trajectory of personality. A large body of research in cultural psychology ( Markus & Kitayama, 1991 ), comparative sociology ( Lincoln & Kalleberg, 1990 ), and international politics ( Norris & Inglehart, 2011 ) provides evidence that Western European and North American cultures emphasize independence in general and strong personal agency in particular and, as a consequence, work-related responsibilities may be associated with increased demands for personal agency in Western cultures. This perspective may be most relevant in understanding age-related trajectories of conscientiousness often found in studies of Western populations: The level of conscientiousness (as reflected in characteristics such as “organized” and “hard-working”) peaks at the prime of work life (i.e., midlife, around 40-50 years of age). In contrast, many non-Western cultures emphasize interdependence with others in general and social duty and obligation in particular ( Markus & Kitayama, 1991 ; Schweder & Bourne, 1982 ; Triandis, 1989 ). In these cultures, individuals must to be attuned to social norms and conform to them regardless of personal agency and, moreover, this need for social adjustment and conformity to work-related norms might be especially strong at the prime of work-life. We thus anticipated that the age-related changes in conscientiousness might be very different in Japan than the U.S. Among Japanese participants, conscientiousness might be particularly low during midlife as individuals emphasize social duty over personal agency.

Relatedly, the cultural difference in endorsement of independence versus interdependence implies that Westerners might be less impacted by various social and contextual events than non-Westerners ( Markus & Kitayama, 1991 ; Oishi, Diener, Napa Scollon, & Biswas-Diener, 2004 ). Thus, non-Westerners may be influenced by an assortment of environmental events including those that are idiosyncratic to each individual or each cohort. In contrast, Westerners may be influenced primarily by environmental events that are pervasive and overwhelming, namely, those that occur equally strongly over most individuals in a given society. In fact, Westerners have been assumed to strive for personal consistencies to a greater extent than non-Westerners do ( Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001 ; Kitayama & Markus, 1999 ). This would mean that there should be more random fluctuations in personality trajectories among Japanese as compared to among Americans. Because of more random fluctuations in trajectories, we expect less dramatic (i.e., more attenuated) age-related mean-level changes in personality.

In the current study, we used two nationally representative samples from the U.S. and Japan to examine age-related changes in personality across the adult lifespan. Participants filled out personality measures twice over either a 4- or 9/10-year period. We employed a multi-level modeling procedure to examine age-related changes in trajectories of personality development and whether these trajectories were moderated by culture.

Participants and Procedure

Participants were from two large national surveys conducted in parallel in the U.S. (the Midlife Development in the U.S.; MIDUS) and Japan (the Midlife in Japan; MIDJA).

The first wave of the MIDUS study (MIDUS 1; 1995-1996) sampled 7,108 English-speaking adults in the United States, aged 20-75 years. The current sample is based on the 6,259 individuals who had at least one wave of personality data (52.5% Female; Mage = 46.85, SD = 12.91). Median level of education was some college education (37.6% high school/GED or less, 30.5% some college, 32.0% have at least a bachelor's degree). In the second wave of data collection (MIDUS 2; 2004-2005), approximately 70 percent of the original sample (n = 4,963) were successfully contacted for follow-up assessments. The average follow-up interval was approximately 9 years. Compared to those who did not provide data for wave 2, participants with complete data were lower in agreeableness ( d = .06), lower in neuroticism ( d = .06), higher in conscientiousness ( d = .18), more likely to be female (55.3% of the follow-up sample were women, compared to 52.5% at wave 1), more highly educated (36% of the follow-up sample had at least a bachelor's degree, compared to 32% at wave 1) and younger on average ( d = .14). Compared to the broader American population of midlife adults, MIDUS is comparable with respect to gender (53% Female for our sample and 51% Female for the general midlife population) but slightly oversamples midlife adults (the current sample had 25.9% adults aged 40-49 compared to 20.4% in the American population of midlife adults).

The first wave of the MIDJA study (MIDJA 1; 2008) sampled 1,027 participants randomly selected from the Tokyo metropolitan area, aged 30-79 years. The current sample is based on the 1,021 individuals who had at least one wave of personality data (50.9% Female; Mage = 54.28, SD = 14.10). Median level of education was some college education (42.8% high school/GED, 25.1% some college, 32.1% have at least a bachelor's degree). In the second wave of data collection (MIDJA 2; 2012), approximately 64 percent of the original sample (n = 657) were successfully contacted for follow-up assessments. The average follow-up interval was approximately 4 years. Compared to those who did not provide data for wave 2, participants with complete data were higher in agreeableness ( d = .18) and higher in conscientiousness ( d = .18). Those with and without data were otherwise comparable with respect to age, gender, education, and other personality traits. Compared to the broader Japanese population of midlife adults, MIDJA is comparable with respect to gender (51% Female for both our sample and the general population) but slightly oversamples older adults (the current sample had 20.1% adults aged 70-79 compared to 16.9% in the Japanese population of midlife adults).

Personality traits

Big Five personality traits were assessed using adjective-based measures. Participants were asked the extent to which each of 25 adjectives described them on a Likert scale ranging from 1( not at all ) to 4( a lot ). The groups of adjectives were: moody, worrying, nervous, calm (for neuroticism; α MIDUS = .74, α MIDJA = .51); outgoing, friendly, lively, active, talkative (for extraversion; α MIDUS = .78, α MIDJA = .83); creative, imaginative, intelligent, curious, broad-minded, sophisticated, adventurous (for openness to experience; α MIDUS = .77, α MIDJA = .84); organized, responsible, hardworking, careless, thorough (for conscientiousness; α MIDUS = .58, α MIDJA = .57); helpful, warm, caring, softhearted, sympathetic (for agreeableness; α MIDUS = .80, α MIDJA = .87). These adjective-based measures of personality correlate well with longer measures of personality and have good construct validity ( Lachman & Weaver, 1997 ; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998 ; Prenda & Lachman, 2001 ). Tests for invariance (configural, metric, and scalar) were conducted across cultures and over time for each of the Big Five traits. As seen in Supplementary Table 1 , there was no scalar invariance across cultures, limiting our ability to make mean-level comparisons across cultures (all ΔRMSEAs> .05), which is often the case in adjective-based measures of personality ( Nye, Roberts, Saucier, & Zhou, 2008 ). However, there was moderate invariance in each of the Big Five traits over time within both MIDUS ( Supplementary Table 2 ) and MIDJA ( Supplementary Table 3 ), allowing us to examine age-related trajectories in each. 1 Nevertheless, we acknowledge the lack of scalar invariance across cultures as a limitation of the current report and hope that culturally invariant measures of personality become available in the near future.

Analytic Plan

As noted, a major drawback of the currently available cross-cultural data on life-course trajectory of personality stems from the fact that the majority of these studies are cross-sectional. To overcome this issue, we used a multi-level modeling procedure, drawing on an approach used by Terracciano et al. (2005) , that enabled us to combine longitudinal changes over 4-9 years. These changes over shorter intervals are estimated from individuals of different ages and are pieced together to estimate the overall life-course trajectory of personality. The two cultural samples were combined for the purposes of multi-level analyses. The multi-level modeling allows for flexibility in the number and spacing of measurement observation across people. Even participants who provided one observation can be used to stabilize estimates of means and variances within an assessment wave. Thus, all available data can be used. The use of two data sets constituted a variant of an accelerated longitudinal design, in which members of different birth years were followed over time. Using this design, we were able to estimate age trajectories over a broad age span by using data collected over shorter intervals. In this way, growth curves can be estimated for individuals of different ages and then pieced together to reveal an overall age trajectory (see Terracciano et al., 2005 , for a similar approach). Age-specific changes (e.g., multiple groups of individuals aged 20-75 followed over a 9-year period) are often used to approximate developmental changes in personality over longer intervals in the absence of available data for all individuals at every age of the lifespan (e.g., one group of 20-year old individuals followed annually for 55 years; Raudenbush & Chan, 1992 ).

Multi-level modeling allows for the estimation of both within person (e.g., how does personality change over time?) and between person (e.g., how do cultures differ in personality?) variation, as well as cross-level products (e.g., does personality change differ between cultures?). Age was grand-mean centered and allowed to vary from wave 1 to wave 2. The linear, quadratic, and cubic functions of age were computed. Prior research suggests that the most complex age-personality relations that can be meaningfully interpreted involve cubic patterns ( Chopik, Edelstein, & Fraley, 2013 ; Terracciano et al., 2005 ). Age and personality traits were treated as time-varying, and culture (-1: MIDJA, 1 = MIDUS) was treated as a time-invariant moderator of age-related trends in personality. Because gender and socio-economic status have been shown to not only explain variation in personality but also important life outcomes ( Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007 ; Schmitt, Realo, Voracek, & Allik, 2008 ), we therefore included them as covariates in all models. Due to the difficulty in creating a common metric of socio-economic status across cultures, we chose educational attainment as a proxy measure for socio-economic status, although we acknowledge the limitations with this approach ( Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, & et al., 2005 ). Gender (-1: men, 1 = women) and education were treated as time-invariant covariates. All analyses were conducted using the SPSS MIXED procedure ( Peugh & Enders, 2005 ).

Because MIDUS (∼9 years) and MIDJA (∼4 years) were collected on different time scales, an adjustment was applied to make the personality scores more comparable. To achieve this, we adopted a similar approach to the one used by Jokela and colleagues (2014) to create an equivalent unit of change when comparing panel studies of personality change. Because previous research on personality change suggests that it changes in a linear fashion over shorter (<10 years) intervals of time, we applied an adjustment to change scores to yield new wave 2 values (representing four-year change) for the MIDUS sample ( Jokela et al., 2014 ; Roberts et al., 2006 ). We began by taking the difference score of each personality trait (Extraversion W2 – Extraversion W1 ) in the MIDUS sample. We then multiplied this score by 4/9 to yield a change score that represents the amount of change that would occur within four years. This new change score was then added to the wave 1 score to produce a new wave 2 score, representing a person's standing on each trait allowing four years of change. For example, a MIDUS participant's scores on extraversion at waves 1 and 2 could be 3.00 and 4.00, respectively. The difference between these two scores (1.00) would be multiplied by 4/9 (.44) and then added to his/her wave 1 score. Thus, the new scores on extraversion at waves 1 and 2 could be 3.00 and 3.44, respectively—capturing the amount of change that would occur within a four-year period, given the knowledge of how he/she changed over a 9-year period, assuming linear change ( Jokela et al., 2014 ).

The purpose of this transformation was to make the data from the two samples more comparable. Importantly, multi-level analyses were also conducted on non-transformed values (as the estimate of age can be interpreted as a one year increase in age); results from these analyses were substantively the same as those presented below.

Preliminary Results

Correlations for age, gender, and personality are presented in Tables 1 (MIDUS) and 2 (MIDJA).

Table 1. Correlations among primary study variables among MIDUS participants.

| Mean ( ) | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Wave 1 | 1. Gender | ||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 46.85 (12.91) | .02 | |||||||||||

| 3. Extraversion | 3.20 (.56) | .06 | -.01 | ||||||||||

| 4. Agreeableness | 3.49 (.49) | .26 | .08 | .53 | |||||||||

| 5. Neuroticism | 2.24 (.66) | .11 | -.14 | -.16 | -.05 | ||||||||

| 6. Conscientiousness | 3.42 (.44) | .11 | .03 | .28 | .29 | -.20 | |||||||

| 7. Openness to E. | 3.02 (.53) | -.08 | -.07 | .51 | .34 | -.17 | .27 | ||||||

| Wave 2 | 8. Extraversion | 3.11 (.57) | .08 | .06 | .36 | -.14 | .21 | .37 | |||||

| 9. Agreeableness | 3.45 (.50) | .28 | .11 | .35 | .05 | .21 | .21 | .50 | |||||

| 10. Neuroticism | 2.07 (.63) | .12 | -.18 | -.12 | -.05 | -.15 | -.14 | -.20 | -.11 | ||||

| 11. Conscientiousness | 3.46 (.45) | .09 | -.03 | .18 | .19 | -.15 | .20 | .26 | .28 | -.20 | |||

| 12. Openness to E. | 2.90 (.54) | -.05 | -.01 | .36 | .22 | -.18 | .23 | .51 | .33 | -.21 | .28 | ||

Note. N = 3850-7019.

p < .001.

Gender: -1 = male, 1 = female.