Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Language/Literature

- Art/Archaeology

- Philosophy/Science

- Epigraphy/Papyrology

- Mythology/Religion

- Publications

The Center for Hellenic Studies

At the table of the gods divine appetites and animal sacrifice.

Citation with persistent identifier:

Carbon, Jan-Mathieu (Mat). “At the Table of the Gods? Divine Appetites and Animal Sacrifice.” CHS Research Bulletin 5, no. 2 (2017). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:CarbonM.At_the_Table_of_the_Gods.2017

Setting the Scene: Myths and Sacrifice

1§1 What did the Greek gods eat and drink? ‘Ambrosia’ and ‘nectar’ are the standard answers that any student of mythology would hurry to propose. [1] But was that always the case, whether in myth or in belief (as far as we can ascertain it)? Without in any way denying the intricate associations of those fabled foods with immortality, the place of animal portions as edible offerings for the gods deserves to be reassessed, not least because animal sacrifice was such a pervasive mode of Greek religious practice.

1§2 Myths relating to sacrificial rituals have been amply studied and far be it from me to offer but a summary here. [2] The fundamental starting point is the story presented by Hesiod concerning the dispute at Mekone. [3] For this feast (not yet a sacrifice proper), Prometheus concealed meaty portions (σάρκες) and innards (ἔγκατα) in the hide (ῥινός) of the animal, while bones (ὀστέα) were wrapped in shining fat to make them more appealing. Zeus was either deceived or not—a much-debated point—but the outcome is made clear by Hesiod or Aeschylus, and was widely accepted. The story provides an aetiology for why humans burned animal bones (again, ὀστέα) wrapped in fat as part of the ritual. In Aeschylus’ version, the burning (πυρώσας) also includes a supplementary element, the long tail (μακρὰ ὀσφῦς) of the animal, to which I will return shortly. [4] The Aeschylean list of Prometheus’ benefactions crucially revolves around augury: burning the thigh bone and the tail is an “impenetrable technique”, or rather a technique of difficult signs (δυστέκμαρτον… τέχνην), and mention is also made of “fiery signs” now made clear, which are still to be connected with sacrifice (see below); [5] the immediately preceding passage also discusses haruspicy, divination through the interpretation of entrails, whereas in Hesiod’s division of the animal the entrails are concealed and apparently reserved for humans.

1§3 Sacrificial rituals have justifiably been said to create “a labyrinth of variations”, [6] but despite their inherent heterogeneity, many persist, not without reason, in focusing on this ‘Promethean’ model as an ideal type, or even in speaking of a Greek “normative animal sacrifice”. [7] Such myths have also been taken as a vision of paradise lost: they are principally seen to outline the hierarchical distinctions between divine beings and mortals. Though they had formerly feasted together, gods now only received the sublimated fatty smoke (κνῖσα, created by the action of θύω, θυσία) from essentially inedible portions of fat and bone, while humans ate meat; gods were immortal and ate separately and differently, while humans, except perhaps for a few blessed heroes, could not dine at their table. [8] Only in a limited number of myths or rituals is it admitted that “the divide” between gods and humans could be “bridged” or “negotiated” by specific or more substantial offerings.

1§4 While fully acknowledging this “theological” or cosmological distinction between gods and mortals, the relevant myths also sketch an histoire des mentalités , informing us about ritual practice and its rationale. [9] Preliminarily, there are two key and interrelated points to be made. The first is that the gods, though fundamentally different, were manifestly perceived to have an appetite for fat and flesh. It is surely taking matters too far to claim, as some have done recently, [10] that they had no taste for, or were in no way thought be nourished by, the offerings made to them. The inherent paradox is perhaps most clear in the famous scene from the Homeric Hymn to Hermes , where the god slaughters two cows and divides them into portions, including the entrails; he roasts and sets all of these aside. [11] Smelling this potential feast, Hermes desires to swallow his rightful portion whole, but does not succumb to the temptation; he thus marks his difference from human meat-eaters, but is still tempted to become one . We would be hard-pressed to deny that other sources fall on both sides of a spectrum, at the center of which was the “inconsistency” that the gods were expected both to eat meat and not to do so. [12] On the one hand, Pindar is loath to call any of the gods a glutton, alluding to the tradition where a distracted Demeter nibbled Pelops’ shoulder at the feast of Tantalus. [13] On the other, Aristophanes employs the idea of the gods receiving pleasing smoke from sacrifices to great comic effect: in both the Birds (1515–1524) and the Plutus (1114–1116), sacrifices are obstructed, with the result that the gods are starving; in the Plutus , for instance, Hermes laments the portions he used to devour from sacrifices, the thigh (or totum pro parte , the fatty bundle containing the thighbone) and the hot entrails . [14] Though the matter would warrant much further investigation than is possible in this short paper, it offers some food for thought. [15] As ancient participants in sacrifices must on occasion or even habitually have done, we can readily apprehend divine appetites for smoke and meat. In other words, the Greek gods were not vegetarians, or at least not strict “Ambrosians”.

1§5 A second point, to be developed further here, is that the divine share in sacrifices was not merely olfactory and that the portions given were not only “inedible”: [16] blood would be sprinkled on altars or poured at cult-sites for the recipients of the rituals, [17] portions beyond the bones and the fat (in fact quite valuable and nutritious in its own right) would be burned for the god, others roasted on the altar and eaten, and still further, special portions could (at least temporarily) be reserved for the gods or to some smaller (but no less significant) degree sampled by them. The practices were much more complex and varied than the simple “Promethean” picture indicates.

1§6 A better approach is not to focus only on sacrifice as a mechanism for the establishment of a hierarchy, but also on its efficacy as a mechanism for communication between the essentially separate human and divine spheres. [18] Sacrifices aimed at forming connections of all sorts: they could be performed to accompany and support the formulation of prayers, to seek to propitiate divine favour, to follow traditions of gift-giving to the gods, etc. On a very practical level, I would argue that communication was achieved through two other interrelated ‘Cs’ of sacrifice: consumption and commensality. The divine portion was either consumed by absorption, by fire, or in a form of presentation, while special portions for human participants were ingested (or put to other uses, especially when inedible parts of the animal were concerned). But this is not all, since a meal was shared: certain explicitly divine portions could be entirely or partly consumed by the priests or other honored individuals; or if the divine portions were completely consumed in the ritual, then we often find that these parts were anatomically connected to the special portions consumed by some human participants. Elaborate modes of commensality between gods and mortals were thus articulated, forming a complex “grammar” of sacrifices. [19] What is more, in highlighting the presence of the gods at sacrifices, particularly by means of their physical manifestations such as their statues, sacrifices recreated to a lesser degree the mythical past when gods and mortals had dined together. [20]

1§7 As part of a larger project on the anatomy of the sacrificial animal in Greece, my paper attempts to substantiate these mythological perspectives on the concrete level of ritual practice. Aside from literary sources, which report intriguing permutations of their own, one main body of evidence consists of normative inscriptions published by Greek communities or their sanctuaries. [21] These are texts that seldom if ever give a full account of how to sacrifice; they usually only provide specific rules such as are appropriate to the cult-site in question or to the privileges of its priestly personnel. However, the details that the inscriptions occasionally reveal can illuminate larger trends: how to cut up a back leg of the animal, for instance, and why this was done. Here, without doing justice to the full diversity of the evidence, I will focus briefly on two crucial locations of consumption and commensality: the altar, where blood was poured and portions burned or roasted for the gods; and the table that could be set up next to the altar or the divine statue to display other offerings.

The Altar: The Tail and Other Bits

2§1 Since it has been well and extensively discussed in recent scholarship, let me only say a few words about one of the principal modes of burning a portion on the altar. As in the “Promethean” sacrifice, this involved wrapping bones, usually the thighbones (sometimes singly, sometimes as a pair) in fat (such as the abdominal fatty fold called the peritoneum, ἐπίπλοον in Greek). The practice was efficacious in several regards. The fat created not only a strong, appealing smell, but as has been elegantly revealed through experiments, also a surprising and impressive surge of flame 6-9 minutes after being placed on an active fire. [22] This was a specific form of conspicuous consumption, then, which could be interpreted as an auspicious sign, following the teaching of Prometheus. Equally importantly, the hams which were ‘butterflied’ and deboned prior to this burning constituted valuable portions of meat which could be eaten or taken away. This relationship between thighbones and thighs from which they were extracted is clearly expressed in one inscription, a regulation from the Attic deme of Phrearrhioi concerning its Eleusinian cults: [23] here, if we reasonably suppose that the lacuna to the right of the text was not too lengthy, we find portions placed on the altar which include μηροί; separately, the inscription stipulates that the portions given to the priests and priestesses (ἱερεώσυνα) include a κωλῆ. [24] The μηροί must be thighbones placed on the altar to be burned, while the κωλῆ was a ham that was deboned: the gods and the human participants thus essentially shared parts of the same limb of the animal. [25]

2§2 In one sacrifice, we are told that a group of officials would receive both this sort of limp ham ( le gigot mou ) as well as “all the things placed over the fire” (τὰ οὑπέρπουρα πάντα). [26] It is not exactly clear what this expression entails, but it cannot have referred to calcined femurs wrapped in fat. One possibility for the things placed “on” or “over” the fire is the tail (other good candidates include the entrails roasted over the altar; see below). As the variation in the Prometheus Bound reveals, a “long tail” was often placed in the fire alongside the thighbones wrapped in fat (μακρὰν ὀσφῦν πυρώσας). Since the work of van Straten, itself going back to Furtwängler and others, it has been well understood that, in vase-painting, a common depiction of a curled element on the altar represents the tail. [27] This is also attractively confirmed by experiments: tails, even broken or set upside down, even when placed in a small amount of heat, always curl upwards. [28] Curling the tail was a critical component of performing “beautiful rites” (ἱερὰ καλά) to please the gods and receive favourable omens from the sacrifice. In an evocative scene, Trygaios in Aristophanes’ Peace directs his slave in the performance of a sacrifice. While instructing him to pay attention to the simultaneous roasting of the entrails, and not to damage the tail (ὀσφῦς, or the sacrum bone at its base) while doing so, he inquires, “is the tail (κέρκος) doing nicely (καλῶς)?”, i.e. is it curling upwards auspiciously? [29]

2§3 The use of the verb πυρόω found in Aeschylus along with the treatment of the fatty bundle containing the bones could be taken to imply that the tail would be completely burned; indeed, calcined caudal vertebrae are regularly found in archaeological deposits. [30] However, there is also epigraphical evidence that the tail would not always be burned whole or completely for the gods. Most likely, this portion would in some cases simply be roasted on the altar-fire. The whole tail (ὀσφῦς, or perhaps a part thereof) is granted with some frequency to priestly officials. [31] In a recent reedition of a regulation from Iasos, we tellingly find one ὀσφῦς which is afterward to be given to the priest “as it is placed” (ὡς ἐπ̣ι̣[τί]θεται), i.e. as a full and intact portion, just as it has been placed on the altar fire for the ritual. Here is another paradigm for divine and human commensality. The tail would be shared between the god on the one hand—the smoke made from the burning or roasting, and the curling of the portion, pointing favourably upward to the heavens—and the priests or other participants on the other—some of the flesh of lower loins and the marrow of the tail which would not have been completely consumed by fire, and could be eaten.

2§4 Many enigmas still remain, due in no small part to the ambiguities of the available evidence. Portions that were deposited on the altar are often simply called τὰ ἱερά. The relatively analogous expression ἱερὰ μοῖρα is occasionally found in inscriptions describing portions for the altar or the priest, and an effort has been made to identify this phrase with the tail or its base, the ὀσφῦς. [32] While it is true that both expressions never occur in the same text, the argument cannot be completely convincing in the absence of further evidence. If the claim were to prove correct, it would suggest that the situation was much like the one we saw at Iasos: the tail would be placed on the altar as a “sacred” or divine portion, roasting and curling, and then be taken away by the officiant. But it is also possible that the referent underlying phrases like ἱερὰ μοῖρα varied, encompassing in some ritual declensions portions of the legs, for instance the shoulder blade removed from the foreleg. [33]

2§5 Another part of the animal which is found in the lists of the regulation from Phrearrhioi is the intriguing half-head (ἡμίκραιρα). This testifies to a common practice of butchery: the skull of the animal would be segmented into two lateral hemispheres, notably for the purpose of extracting its contents (e.g. the brain) and for serving them, often with related portions, such as the tongue and the throat, which were removed separately. Again, this section of the head is commonly found as a priestly perquisite, notably in Attica but also elsewhere. [34] Should we infer that one half of the head was wholly burned for the gods or that it was roasted, as we have seen that the tail might be, and soon after taken by the priestly personnel? We are sadly lacking an inscription which would tell us what happened to the head both on the altar and as a perquisite, or to both sides of the head during a single sacrifice: this would inform us about another potential level of commensality between god and mortal.

Tables and Statues: The Haptic Perception of Entrails and Other Displays

3§1 We have already seen that the entrails of the animal—which could include a wide variety of components, such as the lung, spleen, kidneys, heart, and even the tongue—would typically be roasted over the altar-fire while the fatty bundle burned and the tail curled. A standard view is that these portions would be salted and directly sampled by the participants, much like modern Greek kokoretsi . [35] But it is also well understood that a portion of these viscera was typically reserved for the gods. [36] Passages of Aristophanes’ Birds coupled with epigraphical testimonia from the island of Chios have effectively demonstrated that entrails were expected to be placed “in the hands” of the divine statue, if it held out its hand; or “on its knees”, if it was represented as seated; occasionally, both. [37] Iconographic representations of this phenomenon have been identified by Keesling in the korai from the Athenian Akropolis; one even seems to hold a lumpy object that could be a part of the entrails. [38]

3§2 A somewhat neglected passage illustrates the potential efficacy of placing the entrails in this fashion: this is the supplication which Demaratus is seen to make in Book 6 of Herodotus. Having sacrificed an ox to Zeus in his house in Sparta, at the household altar of Zeus Herkeios (“of the fence”), he calls his mother and places the entrails in her hands in order to entreat her and the god at the same time; the household god presumably did not have a large enough statue for this purpose, though Demaratus appears perhaps to seize his altar, while his mother, holding the entrails, forms another focal point of the entreaty. [39] Oaths normally involved similar ‘haptics’, such as grasping the altar or, more directly, the sacred portions (ἱερά) which were placed upon it. [40]

3§3 All of these rituals, therefore, underscore the importance of physical contact with meat and with sacred portions in particular. In the case of placing the entrails in the hands or on the knees, this must surely have been felt to create a palpable, tangible connection to the gods. It is not particularly clear what would happen to these portions of entrails after they had been deposited in this way: in Aristophanes, they are snatched up by birds, which is comic and perhaps betrays some sense of the reality. [41] Statues with outstretched, empty hands are said, in the Assemblywomen , to appear greedy in always wanting more gifts, meaty or otherwise. [42] On Chios, the portions were clearly intended to be taken away by the priestly officials as their prerogative: they perhaps had to remove them rather quickly, as soon as any prayers or invocations accompanying the sacrifice were completed. Once again, it should be stressed that, though there was no consumption by fire, the divine figure and the priest essentially partook of the same special portions.

3§4 A well-known further declension of this type is that commonly called θεοξένια, though the ritual could be known by a variety of related names (e.g. ξενία, ξενισμός). [43] This literally represented a hosting of the deity or deities for a meal. Here, the statues of the gods would normally be taken out of their sanctuaries and laid upon couches strewn with mattresses and cloths, and presented with offerings on a table. While this may be seen to have recreated a meal with the gods in an even more vivid manner, it is commonly argued that the purpose of the ritual was merely to provide supplementary offerings for the gods, which would eventually be taken away by the priest. The same is said of other offerings which are set out on tables, called τραπεζώματα (“table-offerings”), or παρατιθέμενα (“things set beside” sc. the altar and/or the cult-statue), or still otherwise. Both categories are taken to represent types of gifts which were modeled on human feasts. [44]

3§5 Of the specific offerings or portions of meat presented during a θεοξένια, we are rather poorly informed. As far as τραπεζώματα are concerned, they were extremely varied. A rather stark dichotomy has been suggested between raw portions offered on the table by the altar and cooked ones during a θεοξένια, but this seems untenable. [45] One reason for this is that entrails often feature as part of the table-offerings and that we would expect these to be cooked, usually roasted on the fire. [46] Normally, much of the meat would indeed be placed uncooked on the table, and such offerings would prominently include the leg, whether hind or fore. [47]

3§6 Building on the question of table-offerings, one last element of the divine portion, which is also mentioned in the regulation from the deme of Phrearrhioi, warrants investigation. At Phrearrhioi, the meats in question are called μασχαλίσματα. [48] These could refer to any anatomical extremities which could readily be cut off the body, such as the ears and the feet. According to two ancient lexica, the term μασχάλισμα specifically designated portions of meat deriving from the forelegs or shoulders, perhaps from the armpit (μασχάλη); these were placed on the thighbones and the fat, to be burned in the altar-fire. [49] In a seminal paper, Eran Lupu related this practice to that of ὠμοθετεῖν, placing little raw pieces of meat on the fatty bundle in the altar, which occurs in Homeric sacrifice, but seldom elsewhere by this designation. [50] The passage describing this operation in most detail concerns the sacrifice performed by the swineherd Eumaios upon Odysseus’ return to Ithaka. [51] Having slaughtered a male pig with his attendants, he proceeds to make preliminary or first-offerings (ἀρχόμενος), by selecting a small portion from all the limbs (πάντων… μελέων) and laying these on the fat (ἐς πίονα δημόν, presumably here a shorthand for the fatty bundle, which would include the thighbones or perhaps other bones). [52] There are two important points to be underlined: the morsels are represented as first-offerings, coming relatively near the beginning (ἀρχόμενος) of the sacrificial ritual and being burned for the gods; and in the Homeric version, they represent a small portion of all the limbs (πάντων… μελέων), not just from the forelegs or shoulders. In essence, the ritual process performed by Eumaios distinctly aims to convey through consumption by fire a measure of all the parts of the animal to the gods; it also attributes to this ritual action a clear form of precedence. The swineherd then proceeds to roast the meat and to lay aside a seventh portion for the Nymphs and Hermes, much as we have seen in the case of table-offerings.

3§7 The study of first-fruits or first-offerings is extensive and has recently formed the subject of an excellent book by Jim. [53] Not only could a first-offering occur during sacrifice, but, among many other contexts, it was also a regular occurrence at meals, where a small portion would be preliminary deposited or perhaps burned for the gods before the feast was consumed. [54] My contribution will be limited to two remarks, or ‘first-fruits’ if you will.

3§8 To begin with, offerings placed on tables can demonstrably be viewed as including or constituting first-offerings, and this further emphasizes their importance. An intriguing fragmentary regulation from Attica presents an element of what was set on the table as a καταρχή. [55] A first-offering, probably fleshy rather than vegetal, must be intended, which was to be displayed and used in the ritual; the word also has strong connotations of primacy. [56]

3§9 Second, the order in which the portions were deposited on the table needs to be investigated, since it is clear that in some cases these portions could be partly burned on the altar too. In a celebrated document inscribed on a lead tablet from Selinous, a procedure is described in unusual detail but in close relation to the discussion at hand. [57] The regulation outlines various sacrifices to Zeus and the Tritopatres (divine ancestral figures literally called “Great-Grandfathers”) taking place every four years. In the next year, an animal may also be offered, perhaps to Zeus or to these Tritopatres (side A, lines 18–20):

ἔστο δὲ καὶ θῦμα πεδὰ ϝέτος θύεν. τὰ δὲ ℎιαρὰ τὰ δαμόσια ἐξℎιρέτο καὶ τρά[πεζα]- ν ∶ προθέμεν καὶ ϙολέαν καὶ τἀπὸ τᾶς τραπέζας ∶ ἀπάργματα καὶ τὀστέα κα[τα]- κᾶαι ∙ τὰ κρᾶ μἐχφερέτο, καλέτο [ℎ]όντινα λε͂ι. Translated literally: “It is also possible to sacrifice an animal on the next year. Let him take out the civic sacred objects and set forth a table and a thigh and the first-offerings from the table and the bones burn completely. Let him not carry away the meat, let him call whomever he wants.”

3§10 A sacrifice to the Tritopatres defined earlier in the same regulation (lines 13-16) had also involved the setting out of a table (the text reads only καὶ τράπεζαν), more clearly accompanied by a couch and offerings of cakes and meat during a θεοξένια; this was also followed by the offering of first-fruits (κἀπαρξάμενοι), small pieces derived from the cakes and meat, and the complete burning of these and perhaps other sacred portions (κατακαάντο, with only an implied object in this case). [58] The standard interpretation of the later passage, quoted above, is that it involves the burning of a whole thigh (taking ϙολέαν as an object of κατακᾶαι). [59] This is possible. An alternative view would be to consider that this thigh, as was often the case with the leg (see above), was simply presented raw on the table (forming another object of προθέμεν); [60] the bones (τὀστέα) would then probably represent the femurs extracted from both thighs of the beast, destined for burning on the altar after being covered in fat. At any rate, it is relatively clear that in two sacrifices described at Selinous, as distinctive as they may be, portions from the sacrificial animal and cakes were first displayed on the table; small first-offerings were made from these (τἀπὸ τᾶς τραπέζας ἀπάργματα), by being burned with the bones (καὶ τὀστέα κα[τα]κᾶαι), as we have come to expect. The ἀπάργματα at Selinous may have come from various portions of meat set on the table, including the thigh, not unlike the sampling of limbs performed by Eumaios.

3§11 The important take-away is that the gods were regularly offered little morsels of actual meat from the limbs, such as the shoulder, the leg or other extremities, either directly or after these portions were set and displayed for them on the table. [61] While the burning and roasting was already taking place, first-offerings could be added as additional small portions of raw meat to be completely consumed on the fire and thus by the gods. [62]

4§1 A final point ties in with the wider argument that the portions of the sacrificial animal which the gods received are not to be treated as entirely inedible or negligible. It has been aptly remarked that when an ancient Greek wanted to sacrifice an animal to a god, he or she simply used a phrase like θύω ἱερεῖον, “I sacrifice (lit. make smoke from) a (whole) consecrated animal” to god such-and-such. [63] In other words, the deity was in a certain sense imagined to have received the entirety of the offering.

4§2 Yet aside from making a holocaust—the combustion of a whole animal—or of burning a more substantial portion of meat from the carcass, [64] the repartition was necessarily more selective. There were no doubt basic and functional reasons for this, such as the need to put the slain animal to nutritional and practical use. On a more fundamental level, the question of why such a repartition was made ought not to remain a “mystery”. The meat of the matter is simple: the gods in all cases received significant tokens of a feast. Certain portions could be burned for them on the altar, releasing pleasing smoke and good omens, while others were roasted, achieving similar results; the same or related portions would then be consumed by human participants; others parts could be set aside, displayed, used in some capacity, or even sampled for the divine offerings; most of this would eventually be eaten by the worshippers. Distinct or interconnected modes of consumption and commensality were developed, all of which conveyed close interactions with the gods. Sharing the sacrificial animal was thus both the modus operandi and the essential function of the rituals.

Epigraphical Abbreviations

Bibliography.

Bremmer, J. N. 2007. “Greek Normative Animal Sacrifice.” Blackwell’s Companion to Greek Religion , ed. D. Ogden, 132–144. Malden MA / Oxford.

Burkert, W. 1983. Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth . Trans. P. Bing. Berkeley.

Carbon, J.-M. 2015. “Rereading the Ritual Tablet from Selinous.” In La citt à inquieta, Selinunte tra lex sacra e defixiones, ed. A. Ianucci, F. Muccioli, and M. Zaccarini, 165–204 and 306. Sesto San Giovanni.

———. 2017. “Meaty Perks: Epichoric and Topological Trends.” Animal Sacrifice in the Ancient Greek World , ed. S. Hitch and I. Rutherford, 151–177. Cambridge.

Decourt, J.-C., and A. Tziaphalias. 2015. “Un règlement religieux de la région de Larisa : cultes grecs et « orientaux ».” Kernos 28:13–51.

Dimitrova, N. 2008. “Priestly Prerogatives and Hiera Moira. ” Μικρός ἱερομνήμων, Μελέτες εἰς μνήμην M.H. JAMESON , ed. A. P. Matthaiou and I. Polinskaya, 251–257. Athens.

Durand, J.-L. 1979. “Bêtes grecques. Proposition pour une topologique des corps à manger.” La cuisine du sacrifice en pays grec , ed. M. Detienne and J.-P. Vernant, 133–157. Paris.

———. 1984. “Le faire et le dire. Vers une anthropologie des gestes iconiques.” History and anthropology 1:29–48.

Ekroth, G. 2002. The Sacrificial Rituals of Greek Hero-cults in the Archaic to the Early Hellenistic Periods . Liège.

———. 2008. “Burned, Cooked or Raw? Divine and Human Culinary Desires at Greek Sacrifice.” Transformations in Sacrificial Practices, From Antiquity to Modern Times , ed. E. Stavrianopoulou, A. Michaels and C. Ambos, 87–111. Berlin.

———. 2009. “Thighs or tails?: The osteological evidence as a source for Greek ritual norms.” La norme en matière religieuse en Grèce ancienne , ed. P. Brulé, 125–151. Liège.

———. 2013a. “What we would like the bones to tell us: A sacrificial wish list.” Bones, Behaviour and Belief , ed. G. Ekroth and J. Wallensten, 15–30. Stockholm.

———. 2013b. “Forelegs in Greek cult.” Perspectives on A ncient Greece , ed. A.-L. Schallin, 113–134. Stockholm.

Fabiani, R. 2016. “ I.Iasos 220 and the regulations about the priest of Zeus Megistos: A new edition.” Kernos 29:159–184.

Gill, D. 1974. “Trapezomata: A Neglected Aspect of Greek Sacrifice.” HThR 67:117–137.

Graf, F. 2002. “What is New About Greek Sacrifice?” Kykeon, Studies in Honour of H. S. Versnel , ed. H. F. J. Horstmanshoff, et al., 113–125. Leiden.

Hitch, S. 2009. King of Sacrifice, Ritual and Royal Authority in the Iliad. Cambridge MA.

Jameson, M. H., D. R. Jordan, and R. Kotansky. 1993. A lex sacra from Selinus . Durham.

Jameson, M. H. 2014. Cults and Rites in Ancient Greece, Essays on Religion and Society , ed. A. B. Stallsmith. Cambridge.

Jim, T. S. F. 2014. Sharing with the Gods: Aparchai and Dekatai in Ancient Greece. Oxford.

Kadletz, E. 1984. “The Sacrifice of Eumaios the Pig Herder.” GRBS 25:99–105.

Keesling, C. M. 2003. The Votive Statues of the Athenian Acropolis. Cambridge.

Lupu, E. 2003. “Μασχαλίσματα: A Note on SEG XXXV 113.” Lettered Attica, A Day of Attic Epigraphy , ed. D. Jordan and J. Traill, 69–77. Athens.

Maddoli, G. 2015. “Iasos: vendita del sacerdozio della Madre degli Dei.” SCO 61:101–118.

MachLachlan, B. 1992. “Feasting with Ethiopians: Life on the Fringe.” QUCC 40:15–33.

Morton, J. 2015. “The Experience of Greek Sacrifice: Investigating Fat-Wrapped Thighbones.” Autopsy in Athens , ed. M. M. Miles, 66–75. Oxford.

Naiden, F. S. 2013. Smoke Signals for the Gods, Ancient Greek Sacrifice from the Archaic through the Roman P eriod s. Oxford.

Nock, A. D. 1944. “The cult of heroes.” HThR 37:141–173. Repr. 1972. Essays on Religion and the Ancient World . ed. Z. Stewart. vol. II, 575–602. Oxford.

Osborne, R. 2016. “Sacrificial theologies.” Theologies of Ancient Greek Religion , ed. E. Eidinow, J. Kindt, and R. Osborne, 233–248. Cambridge.

Parker, R. C. T. 2006. “Sale of a Priesthood on Chios.” Χιακὸν συμπόσιον εἰς μνήμην W.G. Forrest, ed. G. E. Malouchou and A. P. Matthaiou, 67–79. Athens.

———. 2011. On Greek Religion . Ithaca.

Pirenne-Delforge, V., and F. Prescendi. 2011. “Nourrir les dieux?” Sacrifice et représentation du divin. Liège.

Puttkammer, F. 1912. Quomodo Graeci carnes victimarum distribuerint . Königsberg.

Rudhardt, J. 1970. “Les mythes grecs relatifs à l’instauration du sacrifice : les rôles corrélatifs de Prométhée et de son fils Deucalion.” MH 27:1–15.

Scullion, S. 2000. “Heroic and Chthonian Sacrifice: New Evidence from Selinous.” ZPE 132:163–171.

Sommerstein, A. H., and I. C. Torrance. 2014. Oaths and Swearing in Ancient Greece. Berlin.

Stavrianopoulou, E., ed. 2006. Ritual and Communication in the Graeco-Roman World. Liège.

Stengel, P. 1910. Opferbräuche der Griechen . Leipzig.

Stocking, C. H. 2017. The Politics of Sacrifice in Early Greek Myth and Poetry. Cambridge.

Tsoukala, V. 2009. “Honorary Shares of Sacrificial Meat in Attic Vase Painting: Visual Signs of Distinction and Civic Identity.” Hesperia 78:1–40.

Van Straten, F. T. 1995. Hier à Kalá, Images of Animal Sacrifice in Archaic and Classical Greece . Leiden.

Vergados, A. 2013. The Homeric Hymn to Hermes. Introduction, Text and Commentary . Berlin.

Vernant, J.-P. 1989. “À la table des hommes. Mythe de fondation du sacrifice chez Hésiode.” La cuisine du sacrifice en pays grec , ed. M. Detienne and J.-P. Vernant, 37–132. Paris.

Versnel, H. S. 1990. Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion, vol. 1: Ter Unus. Isis, Dionysos, Hermes. Three Studies in Henotheism . Leiden.

———. 2011. Coping with the Gods: Wayward Readings in Greek Theology. Leiden.

[1] See for instance the article by A.H. Griffiths, “Ambrosia”, in OCD 3 .

[2] Two fundamental treatments are those of Burkert 1972 and Vernant 1989.

[3] Hesiod Theogony 535–541 and 556–557; see esp. Rudhardt 1970.

[4] Aeschylus Prometheus Bound 493–499. On omitted elements of the θυσία in the Hesiodic myth of Prometheus, see also Ekroth 2008:95.

[5] Aeschylus Prometheus Bound 497–499: δυστέκμαρτον ἐς τέχνην | ὥδωσα θνητούς, καὶ φλογωπὰ σήματα | ἐξωμμάτωσα, πρόσθεν ὄντ᾽ ἐπάργεμα.

[6] For this expression, see Parker (2011:144), in a masterful and cautious overview of the questions and difficulties surrounding the subject (Chp. 5, “Killing, Dining, Communicating”). See also Jameson (2014:113), with an emphasis on contextual analysis: “The various types of formal killing of domestic animals, which we lump together and call sacrifice, were subject to a variety of meanings for the Greeks and were used in a wide range of contexts for diverse purposes.”

[7] Cf. e.g. Graf 2002:117: “one should reconstruct an ideal type, but the variations make it difficult to judge what this norm should be…”; and see also the title of the overview by Bremmer 2007, though himself accounting (144) for the “richness of… meanings” and warning “not to fall into the temptation to reduce them to one formula, however attractive”.

[8] Ekroth 2008:87: “Ancient Greek animal sacrifice focused, to a large extent, on the distinctions between gods and men. These differences were highlighted not only by how the animal was divided but also by the selection of which parts were burnt to create smoke and which parts were cooked to be eaten. On the other hand, the ritual world of the Greeks encompassed possibilities to abridge these distinctions…” See also the essays in Pirenne-Delforge and Prescendi 2011.

[9] For a recent effort at revising models of Greek sacrifice, with a (debatable) emphasis on theology and the similarity between gods and humans, see Osborne 2016.

[10] Ekroth 2008:87: “…offerings, which seem to have been more adapted to the human participants’ tastes than to those of the immortal divinities”; or 93: “To see the transformation of the divine share by burning it as linked to the immortality of the gods is surely correct. Gods do not eat, since they are immortal, and there was no ancient Greek notion of the human worshippers sacrificing animals in order to feed the gods.”

[11] Homeric Hymn to Hermes 116–137. Vergados’ interpretation (2013:327–329) of Hermes’ gestures as a prototype of the ritual of setting offerings on a table ( trapezomata ) is compelling; but this was a form or a component of ‘sacrifice’ as a broader category. See also Ekroth 2008:103.

[12] Reports of gods eating meat or other parts of an animal are naturally exceptional yet paradoxically numerous; a full inventory would be lengthy. Homer depicts the gods dining with the Ethiopians and other peoples “on the fringe”; see e.g. MacLachlan 1992. For the idea of “inconsistencies” in Greek religion, see Versnel 1990 and 2011 (esp. 309–377 on Hermes and his hunger).

[13] On this myth, see Ekroth 2008:96 with n51; for the anxiety of Pindar in accepting Demeter’s consumption, Olympian 1, 52–53: ἐμοὶ δ᾽ ἄπορα γαστρίμαργον μακάρων τιν᾽ εἰπεῖν. Of course, the horror of the poet is in no small part attributable to the fact that the shoulder, whether consisting of meat or bone (or both), is human in this case; but “gluttony” is nonetheless at the heart of the aporia and its euphemistic expression.

[14] Aristophanes Wealth 1128: οἴμοι δὲ κωλῆς ἣν ἐγὼ κατήσθιον; 1130: σπλάγχνων τε θερμῶν ὧν ἐγὼ κατήσθιον.

[15] See now Stocking 2017 for a more detailed and comparative treatment of many of the relevant Greek myths, with a commendable emphasis on the “commensal politics” of sacrifice.

[16] Cf. e.g. Jameson 2014:148: “Animal sacrifice was regularly accompanied by the burning of grains and cakes… These, more than the burning of primarily inedible parts of the animal, carried with them the concept of food and of eating” or Durand (1976:156): “immangeables”.

[17] See van Straten 1995:104–105, for the use of blood to sprinkle or pour on altars, noting in particular Lucian’s depiction ( On sacrifices ), of gods swarming like flies around the altar in order to drink it; cf. also Ekroth (2002:242–276).

[18] See now Naiden 2013:3–38, but cf. already the essays in Stavrianopoulou 2006; Parker 2011, chp. 5.

[19] The phrase is a suggestion of Graf (2002:117): “a grammar of sacrifice, must have existed in the heads of the Greeks…”

[20] For example, the myths concerning Mekone, or those of Tantalus or of Ixion, all point to this mythical past. For the issue of table fellowship, cf. esp. the arguments of Nock 1944 against this notion.

[21] For these inscriptions, often called “sacred laws”, see now CGRN , with further refs.

[22] Morton 2015.

[23] NGSL 3 / CGRN 103 (ca. 300–250 BC), lines 15–18: ἐπὶ δὲ τοὺς βωμοὺς [..?..] | μηροὺς, μασχαλίσματα, ἡμίκ<ρ>α[ιραν ..?.. μ]|ηροὺς, μασχαλίσματα, ἡμίκραιρ[αν ..?..]. For the priestly prerogatives in this text, cf. line 5 [ἱερεώσ]υνα κωλῆν, πλευρὸν, ἰ<σ>χ[ίον]; and 19–21: ἱερεώσυν[α ..?.. τοῖν θε]|οῖν τῶν βω<μ>ῶν τῆι ἱερείαι κα[ὶ ..?.. (κωλῆν), πλε]υρὸν, ἰσχίον.

[24] This was a standard priestly perquisite in Attica and elsewhere, see now Carbon 2017. For legs in Attic iconography, see Tsoukala 2009.

[25] See already Durand 1979:157.

[26] Le gigot mou : the phrase is that of Durand (1984:32). The inscription in question is a decree from Haliartos concerning the Ptoia, NGSL 11 (ca. 235 BC vel paulum post ), lines 23–25: διδόσθη δὲ τῦ ἀρχῦ κὴ τῦς πολεμά[ρχυς κὴ τῦς] | τεθμοφουλάκεσσι τὰ οὑπέρπουρα | πάντα κὴ τὰν κωλίαν. The term is distinctive and may have encompassed all of the portions that were not completely destroyed in the fire on the altar or all those which were roasted over it.

[27] Van Straten 1995:118–120 and 128–130.

[28] Ekroth 2013a:20 with n29; Morton 2015.

[29] Schol. ad Aristophanes Peace 1053: ἀπὸ τῆς ὀσφύος: ἐπῖ τοῦ βωμοῦ τὰ σπλάγχνα ὄπτα ἐν σιγῇ. λέγει οὖν, ἀπὸ τῆς ὀσφύος τὸν ὀβελίσκον ἀπάγαγε. οἷον πρόσεχε μὴ ἅψῃ αὐτῆς. ταύτῃ γὰρ μαντεύονται. Cf. also schol. ad 1054: ἡ κέρκος ποιεῖ: ἡ οὐρὰ καλὰ σημαίνει. ἔθος γὰρ εἶχον τὴν ὀσφῦν καὶ τὴν κέρκον ἐπιτιθέναι τῷ πυρὶ καὶ ἐξ αὐτῶν σημείοις τισὶ κατανοεῖν εἰ εὐπρόσδεκτος ἡ θυσία.

[30] See van Straten (cf. n27 above) and Ekroth 2009.

[31] In the present state of the evidence, this priestly portion appears to be particularly prevalent in the general area of Iasos, for instance at nearby Miletos: LSAM 46 / CGRN 100 (ca. 300–275 BC), lines 2 and 6; LSAM 50 / CGRN 201 (ca. 200 BC but a copy from a text of 447/6 BC), lines 9 and 35–38 (boiled). If we include the πρότμησις as equivalent to the ὀσφῦς, then a greater prevalence of this priestly portion can be observed in the Ionian sphere: LSAM 1 / CGRN 120 (Sinope, a Milesian colony; ca. 350–250 BC), line 8; Parker 2006 / CGRN 37 (Chios, ca. 425–375 BC), line 11.

[32] Dimitrova 2008. Cf. still the essential discussion of Puttkammer 1912:11–12 etc. On the altar: LSAM 24 / CGRN 76 (Erythrai, ca. 380–360 BC), lines 33–34. Priestly portion, all from Miletos: LSAM 44 / CGRN 39 (ca. 400 BC), lines 6–7; LSAM 48 / CGRN 138 (275/4 BC), line 17; LSAM 52B (AD 14–50), line 5.

[33] For the term θεομοιρία found on Kos and evidence for divine portions deriving from the front limb, such as the shoulder blade, see Carbon 2017; for forelegs more generally, see Ekroth 2013b. Add also now the new evidence from the detailed rules for sacrifice ἑλληνικῶι νόμωι in the cult of a Semitic goddess at Marmarini near Larisa in Thessaly, Decourt and Tziaphalias 2015. There (face B, lines 41–43), the foreleg (τὸ σκ̣έλο[ς] τὸ ἀπὸ τοῦ στήθους) is to be burned, or perhaps only its bones, such as the scapula, as the phrase deriving “from the chest” (τὸ ἀπὸ τοῦ στήθους) might imply (this appears to be the same chest or breast which was presented boiled on the table, see n47 below); a part of the foreleg or its bones were clearly wrapped in the omentum (ἐπίπλουν) to catch fire.

[34] Cf. IG II 2 1359 / LSCG 29 / CGRN 61 (Athens, ca. 350 BC), line 8; Amipsias fr. 7 (Kassel-Austin; ap. Athen. 368e). See also the more puzzling “half-head” “of sausage” (or half the skull “filled with tripe”?), listed as a table-offering at Aixone, CGRN 57 (ca. 400–375 BC), passim : ἐπὶ δὲ τὴν τράπεζαν κωλῆν, πλευρὸν ἰσχίο, ἡμίκραιραν χορδῆς. Yet the half-head is conspicuously absent in the lists of ἱερεώσυνα found in the regulation from Phrearrhioi (n23 above). In the new sale of the priesthood of Meter at Iasos (Maddoli 2015 / CGRN 196, lines 13–14), the following portions, all properly belonging to the area of the head, are given: καὶ τῆς κ̣εφαλῆς τὸ ἥμι̣|συ καὶ γλῶσσαν καὶ ἐγκέφαλον καὶ τράχηλον. For the left cheek given to a priestess on Chios, another form of half-head, see Parker 2006 / CGRN 37 (ca. 425–375 BC), line 11: <γ>νάθον εὐ[ώ]νυμο[ν].

[35] Cf. Ekroth 2008:93.

[36] For some of the entrails being directly burned on the altar-fire in a sacrifice ἑλληνικῶι νόμωι, see again Decourt and Tziaphalias 2015. At lines 40–41, a relatively canonical list of entrails, including the tongue, is given to the priestess, though the items are to be boiled rather than roasted; only the left kidney is given, while the right one and the heart are to be used as burnt offerings (line 43: εἰς ἱερὰ ἐπὶ τὸ πῦρ̣, as the text should correctly read; see also BE 2016 no. 291-293 for corrections to this inscription).

[37] Statues on Chios: see now CGRN 41, lines 12–13, with further refs.; cf. esp. van Straten 1995:131–133, quoting Aristophanes Birds 975: καὶ φιάλην δοῦναι καὶ σπλάγχνων χεῖρ’ ἐνιπλῆσαι.

[38] Keesling 2003:158–161, with further discussion.

[39] Herodotus VI 67–68: ἦσαν μὲν δὴ γυμνοπαιδίαι… κατακαλυψάμενος ἤιε ἐκ τοῦ θεήτρου ἐς τὰ ἑωυτοῦ οἰκία, αὐτίκα δὲ παρασκευασάμενος ἔθυε τῷ Διὶ βοῦν, θύσας δὲ τὴν μητέρα ἐκάλεσε. ἀπικομένῃ δὲ τῇ μητρὶ ἐσθεὶς ἐς τὰς χεῖράς οἱ τῶν σπλάγχνων κατικέτευε, λέγων τοιάδε· ὦ μῆτερ, θεῶν σε τῶν τε ἄλλων καταπτόμενος ἱκετεύω καὶ τοῦ Ἑρκείου Διὸς τοῦδε, φράσαι μοι τὴν ἀληθείην, τίς μεο ἐστὶ πατὴρ ὀρθῷ λόγῳ”. As How and Wells comment ad loc., καταπτόμενος implies a concrete gesture of holding, possibly of the altar of Zeus Herkeios (designated here with the deictic τοῦδε), while the entrails lie in the hands of the supplicanda , Demaratus’ mother.

[40] On rituals during oaths, see now Sommerstein and Torrance 2014:132–155. Seizing the altar: e.g. IG II 2 1237 / LSCG 19 (phratry of Demotionidai in Athens, 396/5 BC), lines 75–76: μαρτυρε̑ν δὲ τὸς μάρτυρας καὶ ἐπομνύναι ἐχομένος το̑ βωμο̑. Sacred portions: e.g. Aeschines I 114 (during antomosia ): ἐπιστὰς τῇ κατηγορίᾳ ἐπὶ τοῦ δικαστηρίου, καὶ λαβὼν εἰς τὴν ἑαυτοῦ χεῖρα τὰ ἱερά, καὶ ὀμόσας μὴ λαβεῖν δῶρα μηδὲ λήψεσθαι …

[41] Aristophanes Birds 519–520: ἵν’ ὅταν θύων τις ἔπειτ’ αὐτοῖς εἰς τὴν χεῖρ’, ὡς νόμος ἐστίν, τὰ σπλάγχνα διδῷ, τοῦ Διὸς αὐτοὶ πρότεροι τὰ σπλάγχνα λάβωσιν.

[42] Aristophanes Assemblywomen 778–783: οὐ γὰρ πάτριον τοῦτ᾽ ἐστίν, ἀλλὰ λαμβάνειν | ἡμᾶς μόνον δεῖ νὴ Δία· καὶ γὰρ οἱ θεοί | γνώσει δ᾽ ἀπὸ τῶν χειρῶν γε τῶν ἀγαλμάτων | ὅταν γὰρ εὐχώμεσθα διδόναι τἀγαθά, | ἕστηκεν ἐκτείνοντα τὴν χεῖρ᾽ ὑπτίαν | οὐχ ὥς τι δώσοντ᾽ ἀλλ᾽ ὅπως τι λήψεται.

[43] Jameson 2014:145–176.

[44] Ekroth 2008:104: “it is tempting to suggest that the practice of offering the gods meat actually was inspired by and developed from the custom of giving choice portions to the priest or priestess at a thysia . The trapezomata and theoxenia constituted one further means of honouring the gods by adopting (and elaborating) a practice prevalent among men”.

[45] Ekroth 2008:101: “At the trapezomata , there is no cooking at all, since the meat was raw when presented to the god on the table near the altar. A practical explanation may be that if the meat was to be visible during the part of the sacrifice which was acted out around the altar, only raw meat would be available at such an early stage of the ritual. But cooking also belongs to the human part of the sacrifice and the fact that the meat was raw may have been of central importance”.

[46] For entrails as part of the trapezomata , accompanied with a triple-portion of flesh when the sacrifice of an ox is at play, cf. LSAM 24 / CGRN 76 (Erythrai, ca. 380–360 BC), lines 13–20: [ἢν δὲ βοῦν θύῃ τῶι Ἀ]|πόλλωνι ἢ τῶι Ἀσκλ[ηπιῶι ἐπὶ τὴν τρά]|πεζαν παρατιθέτω τ[ῶι θεῶι ἑκατέρωι] | βοιὸς τρεῖς σάρκας κ̣[αὶ σπλάγχνα καὶ] | τῶι ἱρεῖ δυ’ ὀβολούς. ἢν [δὲ τῶι ἑτέρωι ἱ]|ρέον θύῃ τέλεον, παρατιθ[έτω ἑκατέρωι] | ἐπὶ τὴν τράπεζαν τρία κρέ[α καὶ σπλάγ]|χνα καὶ τῶι ἱρεῖ ὀβολόν. For an unusual case of limbs being boiled whole and deposited overnight on a table beside the statue of a hero before being distributed, see the endowment of Kritolaos at Aigiale, IG XII.7 515 / LSS 61 (end of 2nd c. BC), lines 77–79: καὶ τοῦ κριοῦ τὰ κρέα | [ὁλο]μελῆ ἀποζέσαντες παρατιθέτωσαν τῷ ἀγάλματι κ̣αὶ τὴν παράθεσιν (i.e. a dinner). Other evidence for cooked portions placed on the table now comes from the cult at Marmarini near Larisa in Thessaly, cf. Decourt and Tziaphalias 2015; among the table-offerings (face B, line 35, φέρειν δεῖ ἐπὶ τὴν τράπεζαν τὰ ἐπιτιθέμενα…), we find both a boiled breast (or ribcage) and a raw leg derived “from the sacrificial animal” (face B, lines 39–38: ἀπὸ τοῦ ἱεροῦ τὸ στῆθος ἑφθὸν ἐπὶ τὴν τράπεζαν καὶ τὸ σκέλος ὠμόν, taking ἀπὸ τοῦ ἱεροῦ—see LSJ s.v. ἱερός III.1—with this phrase and not with the preceding mention of wine, pace edd. pr.).

[47] Leg: cf. e.g. CGRN 98 (Erythrai, ca. 350–300 BC), face A, lines 15–16: καὶ τὸ σκέλος τὸ πα[ρὰ τὸν βωμὸν πα]|ρατιθέμενον κα[ὶ —]; IvP II 251 / LSAM 13 / CGRN 206 (Pergamon, 2 nd c. BC), lines 12–15: λαμβάνειν δὲ | καὶ γέρα τῶν θυομένων ἱερείων ἐν τῶι ἱερῶι | πάντων σκέλος δεξιὸν καὶ τὰ δέρματα καὶ τἆλλα̣ | τραπεζώματα πάντα τὰ παρατιθέμεν[α].

[48] See n above.

[49] Cf. Hesychius s.v. μασχάλισμα· … καὶ τὰ ἐπιτιθέμενα ἀπὸ τῶν ὤμων κρέα ἐν ταῖς τῶν θεῶν θυσίαις; Suda s.v. … σημαίνει δὲ ἡ λέξις καὶ τὰ τοῖς μηροῖς ἐπιτιθέμενα ἀπὸ τῶν ὤμων κρέα ἐν ταῖς τῶν θεῶν θυσίαις.

[50] Lupu 2003; see also the commentary at NGSL 3.

[51] On this sacrifice, see Kadletz 1984; on Homeric sacrifice, see also Hitch 2009.

[52] Homer Odyssey xiv 427: ὁ δὲ ὠμοθετεῖτο συβώτης, | πάντων ἀρχόμενος μελέων, ἐς πίονα δημόν | καὶ τὰ μὲν ἐν πυρὶ βάλλε… Cp. e.g. Odyssey iii 456–460 for a summary of the overall process.

[53] On the vocabulary of first-offerings, see Jim 2014:28–58; but note that, regarding several terms and inscriptions mentioned here, I tend to differ from her interpretation.

[54] See Jim 2014:117–129 on offerings at meals.

[55] IG II² 1359 / LSCG 29 / CGRN 61 (Athens, ca. 350 BC): ἐπὶ τράπεζαν καταρχὴ[ν]; note also lines 1 and 9 of the same inscription. Jim 2014:43n62, finds this use “obscure”; for κατάρχεσθαι in the sense of sacrificial preliminaries, see Jim 2014:32, where, as she admits, it is not always clear what is meant by the verb. A possible parallel may be found in an interesting cult regulation for Meter from Minoa on the island of Amorgos, dating to the first-century BC. A passage from the inscription ( IG XII.7 237 / LSCG 103 / CGRN 195, lines 15–21) reads as follows: παρατιθέτω]|σαν δὲ καὶ [ἐπ]ὶ τὴν τρά[πεζαν τοῦ μὲν βοὸς — 5–8 — καὶ] | γλῶσσαν καὶ σάρκας τρεῖς [καὶ — — — — —] | ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τῶν ἄλλων [ἱερείων· τῶν δὲ παρατιθεμένων(?)] | τῆι θεῶι ἐπὶ τὴν τράπεζαν ἔσ[τω τὸ μὲν — 8–11 — μέ]|ρος τῆς ἱερείας, τὰ δὲ λοιπὰ τῶν ἐπα[— — 12–15 — —] | ἐπὰν δὲ…. The first clause requires the tongue of the animal (γλῶσσαν) and three portions of flesh (σάρκας τρεῖς), probably from an ox, as well as others now missing, to be placed on the table. The second describes what will happen after these have been reserved for the goddess: a portion of the table-offerings is to belong to the priestess; the remainder (τὰ δὲ λοιπὰ…) are to be treated differently. The traces τῶν ἐπα[… might suggest that the portions on the table were not merely envisaged as being “reserved” or “set aside” for the goddess, but rather as ἐπά[ργματων], first-offerings which were explicitly consecrated to her (i.e. burned on the altar?). Yet this reading is problematic. We would instead expect τῶν ἐπα[… to contain a genitive of possession, qualifying the recipient of “the remainder” of these portions, much like τῆς ἱερείας; the bolder correction τῶν ἐπ<ι>[μηνίων] might therefore be proposed (ἐπιμήνιοι recur in the inscription, cf. lines 9, 11, 25–26, 35 etc, as subsidiary cult officials responsible for the substance of the decree, the donation to the cult of Meter by Hegesarete).

[56] The word ἀρχή can of course denote both a “beginning” and “sovereignty” (cf. LSJ s.v.): it can be seen as appropriate to rites for the gods which occur first in ritual order or with some form of precedence during the rites at the altar, as well as in priority for these supreme beings.

[57] See Jameson, Jordan and Kotansky 1993 (cf. also CGRN 13, ca. 500–450 BC).

[58] Face A, lines 14–16: καὶ τράπεζαν καὶ κλίναν κἐνβαλέτο καθαρὸν ℎε̑μα καὶ στεφά|νος ἐλαίας καὶ μελίκρατα ἐν καιναῖς ποτερίδε̣[σ(σ)]ι καὶ ∶ πλάσματα καὶ κρᾶ κἀπ|αρξάμενοι κατακαάντο.

[59] So Jameson, Jordan and Kotansky 1993; see Scullion 2000.

[60] προτίθημι can be used of a τράπεζα just as much as the meal it can contain, see LSJ s.v. See already Carbon 2015 for this proposal.

[61] In the new regulation from Marmarini/Larisa (Decourt and Tziaphalias 2015; see n33 and n46 above), an ἀκροκόλιον (i.e. ἀκροκώλιον) δεξιόν is offered on the altar-fire (face B, lines 41–43); this may well have belonged to the extremities of the right foreleg, such as the arm-pit or the foot (alternatively, perhaps to an ear or another such delicacy).

[62] This is notably clear from the proceedings in Aristophanes’ Peace. Hierokles the oracle-monger urges Trygaios to proceed with the first-offerings while the tail is still burning and the roasting is progressing (1057): ἄγε νυν ἀπάρχου κᾆτα δὸς τἀπάργματα. Avoiding being rushed, Trygaios responds (1058) that it is better to continue roasting (sc. the entrails and the rest) on the fire first (and presumably to make first-offerings later). This passage indicates that first-offerings were not always offered first in ritual order, though that would often be expected. It further suggests that the connotation of “primacy” in the terms “first-fruits” or “first-offerings” was notably related to their quality as divine gifts.

[63] See Jim 2014:56–57, acutely noting that “ideologically the gods were presented with the whole animal”.

[64] For the neologism “moirocaust” to denote the burning of a more substantial portion of meat from an animal, see Scullion 2000:165–166. One instance is the ritual called ἐνατεύειν discussed by Scullion, involving a division in nine parts. It seems to me preferable to continue to use the ancient Greek terms for these sacrificial varieties and declensions.

Re Think everything you thought you Knew

- Search the Site

- Books By Greg

- I Bible Interpretation

- II The Old Testament

- III The New Testament

- IV Church History

- VI Apologetics

- VII Christian Living

- VIII Philosophy

- IX Contemporary Science, Free Will and Time

- About ReKnew

- FAQ for Greg Boyd

- Other Resources

- Testimonies

We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Why Did God Require Animal Sacrifice in the Old Testament?

I have a question about the atonement. Why did YHWH in the OT demand that people sacrifice animals? And if these sacrifices anticipated the ultimate sacrifice of the Messiah, as the author of Hebrews says, doesn’t this imply that Jesus’ death was necessary for God to forgive us? But why would God need his Son to die to forgive us? Did the Father need to kill his Son to placate his wrath, as I was taught? And finally, how does all this sacrifice stuff relate to the Christus Victor view of atonement that you advocate?

Great question. I do not for a moment believe the Father needed to vent his wrath on Jesus in order to forgive us. For more about why I find this common belief to be objectionable, go here.

The first thing I’d say about animal sacrifices in the Old Testament is that it’s important to know that all Ancient Near Eastern people sacrificed animals as a way of appeasing the gods. In fact, this has been a staple of human religion around the world from the start, as Genesis 4 (with Cain and Able’s sacrifice) illustrates. Interestingly enough, there’s no suggestion in Genesis 4 that God asked Cain and/or Able to sacrifice anything. They just started doing this. I suspect this reflects the fallen human sense that we are estranged from God and that he’s angry about it, so we instinctively want to do something to rectify this.

In any case, in light of the almost universal religious practice of sacrificing animals, it seems reasonable to assume that the Israelites had been sacrificing animals a long time before Yahweh ever began to instruct them. In fact, the way some Old Testament authors refer to the sacrifice as producing “a pleasing aroma to God” reflects the cultural indebtedness of this practice, for we find this same phrase used by other people long before the Israelites. Since God must relate to people where they are at in order to gradually lead them forward, just as a missionary must do when going to pagan cultures, it seems to me that God accepted this barbaric practice as an accommodation to his fallen, culturally conditioned people. In fact, Leviticus 17:7 indicates that God commanded animal sacrifices as a way of helping his people to stop worshipping demons. So, as is often the case with God’s dealings with fallen people, it seems this command doesn’t reflect God’s ideal will. It rather reflects his accommodating will as God must choose between the lesser of two evils. (I could give hundreds of examples of this in the Old Testament, e.g. why God allowed polygamy and concubines.)

At the same time, God always brings good out of evil. So while God accepted this practice, he changed its meaning. Instead of being used to appease God’s wrath, as pagans have always believed, these sacrifices were used to remind people that covenant breaking with the God of life inevitably leads to death. This is why animals were sacrificed by being cut in two whenever covenants were made. (In fact, the Hebrew phrase for “making a covenant” is literally “to cut a covenant”—referring to the animal that was cut in two to make the covenant). The parties entering into a covenant would walk between the animal parts after exchanging vows as a way of saying, “If I break my covenant vows, let it be to me as it is this animal.” A clear example of this is found in God’s covenant with Abraham in Genesis 15 (though, interestingly enough, only Yahweh walks between the animal parts, anticipating the crucifixion when God would be faithful on behalf of humans when we are unfaithful).

So you see that animals were sacrificed not because God needed them to forgive people but because his people needed them to remember the death consequences of sin and to therefore repent when they’d broken covenant with God. Later in Israel’s history, when people began sacrificing animals without repenting in their hearts, the Lord told them (through prophets like Isaiah, Hosea and Amos) that he despised their sacrifices, for they are meaningless without a change in heart.

So, how does this relate to the Christus Victor understanding of the atonement? We’re taught that the reason the Son of God became a human and died on the cross was to “destroy the one who had the power of death –the devil” (Heb 2:14; cf. I Jn 3:8). This tells us a lot about why it is that covenant breaking with God leads to death. Breaking covenant leads to death not because God is unable to freely forgive us unless he first vents his wrath by killing someone. We find God forgiving people without requiring any sacrifice throughout the Bible. Breaking covenant with God rather leads to death because all sin (which is at root breaking covenant with God) enslaves us to Satan, “the destroyer” (Heb 2:14; cf. Jn 8:34; Rev. 9:11) and thus enslaves us in the kingdom of darkness (Col.1:13; cf. Ac 26:18).

The only way God could redeem us from this dire situation was for God himself to become a human and become the first faithful human covenant partner and to then bear the full death-consequences of our covenant breaking on our behalf, which is what Jesus does on the cross. This unsurpassable expression of self-sacrificial love in principle overthrew the kingdom of darkness (Col 2:14-15), just as light dispels darkness, and this in turn frees us to be united with Christ, to share in his covenant faithfulness, to receive God’s empowering grace, to be filled with God’s empowering Spirit and to thereby begin to live in a right relationship with God (which is what Scripture means when it talks about us being “righteous” before God).

There is, of course, a lot more that could be said about what Christ accomplished on the cross and how it redeems us, but I hope this suffices to show how the sacrifices in the Old Testament relate to the Christus Victor theme of the atonement.

Keep thinking…as an act of worship to God!

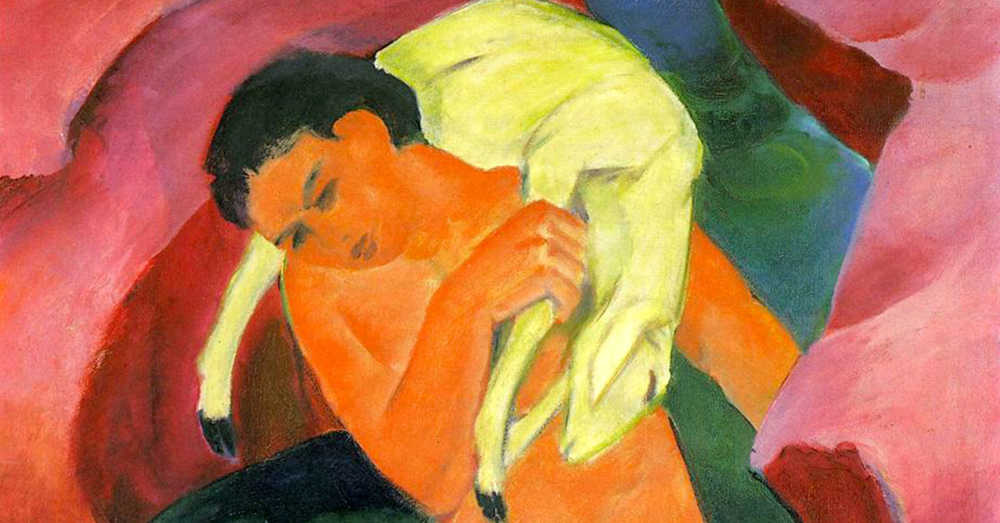

___ art:”Young Boy with a Lamb” by: Franz Marc date: 1911

Category: Q&A Tags: Animal Sacrifice , Atonement , Christus Victor , Forgiveness , God , God's Wrath , Satan Topics: Christus Victor view of Atonement , Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Related Reading

If God is already doing the most he can do, how does prayer increase his influence? April 27, 2011

Question: If God always does the most that he can in every tragic situation, as you claim in Satan and the Problem of Evil, how can you believe that prayer increases his influence, as you also claim? It seems if you grant that prayer increases God’s influence, you have to deny God was previously doing…

Not the God You Were Expecting March 25, 2013

Thomas Hawk via Compfight Micah J. Murray posted a reflection today titled The God Who Bleeds. In contrast to Mark Driscoll’s “Pride Fighter,” this God allowed himself to get beat up and killed while all his closest friends ran and hid and denied they even knew him. What kind of a God does this? The kind…

The Nature of Human Rebellion July 24, 2018

God placed Adam in the Garden and instructed him to “protect” it (Gen. 2:15). The word is often translated “till” or “keep,” implying that Adam’s main responsibility was to protect the pristine Garden from weeds. This is certainly a possible interpretation of this word, but in light of the cunning serpent that shows up in…

Jesus: Our Vision of God January 17, 2017

At the beginning of his Gospel John taught that “no one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known” (Jn 1:18). He is claiming that, outside of Christ, no one has ever truly known God. In the…

What Are the “Keys to the Kingdom”? September 2, 2015

And I tell you that you are Peter [petros = rock], and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on…

A Revelation of Beauty Through Ugliness March 20, 2013

In my recent post, Getting Honest About the Dark Side of the Bible, I enlisted no less an authority than John Calvin to support my claim that we need to be forthright in acknowledging that some of the portraits of God in the OT are, as he said, “savage” and “barbaric.” What else can we…

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Greek gods and religious practices.

Terracotta aryballos (oil flask)

Signed by Nearchos as potter

Bronze Herakles

Bronze mirror with a support in the form of a nude girl

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water)

Attributed to Lydos

Terracotta kylix (drinking cup)

Attributed to the Amasis Painter

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora

Attributed to the Euphiletos Painter

Terracotta amphora (jar)

Signed by Andokides as potter

Attributed to the Kleophrades Painter

Terracotta statuette of Nike, the personification of victory

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask)

Attributed to the Tithonos Painter

Attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter

Attributed to the Nikon Painter

Terracotta stamnos (jar)

Attributed to the Menelaos Painter

Attributed to the Sabouroff Painter

Attributed to the Phiale Painter

Marble head of a woman wearing diadem and veil

Terracotta oinochoe: chous (jug)

Attributed to the Meidias Painter

Ganymede jewelry

Set of jewelry

Gold stater

Marble head of Athena

Bronze statue of Eros sleeping

Ten marble fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief

Limestone statue of a veiled female votary

Marble head of a deity wearing a Dionysiac fillet

Marble statue of an old woman

Marble statuette of young Dionysos

Colette Hemingway Independent Scholar

Seán Hemingway Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2003

The ancient Greeks worshipped many gods, each with a distinct personality and domain. Greek myths explained the origins of the gods and their individual relations with mankind. The art of Archaic and Classical Greece illustrates many mythological episodes, including an established iconography of attributes that identify each god. There were twelve principal deities in the Greek pantheon. Foremost was Zeus, the sky god and father of the gods, to whom the ox and the oak tree were sacred; his two brothers, Hades and Poseidon, reigned over the Underworld and the sea, respectively. Hera, Zeus’s sister and wife, was queen of the gods; she is frequently depicted wearing a tall crown, or polos. Wise Athena, the patron goddess of Athens ( 1996.178 ), who typically appears in full armor with her aegis (a goatskin with a snaky fringe), helmet, and spear ( 07.286.79 ), was also the patroness of weaving and carpentry. The owl and the olive tree were sacred to her. Youthful Apollo ( 53.224 ), who is often represented with the kithara , was the god of music and prophecy. Judging from his many cult sites, he was one of the most important gods in Greek religion. His main sanctuary at Delphi, where Greeks came to ask questions of the oracle, was considered to be the center of the universe ( 63.11.6 ). Apollo’s twin sister Artemis, patroness of hunting, often carried a bow and quiver. Hermes ( 25.78.2 ), with his winged sandals and elaborate herald’s staff, the kerykeion, was the messenger god. Other important deities were Aphrodite, the goddess of love; Dionysos, the god of wine and theater ; Ares, the god of war ; and the lame Hephaistos, the god of metalworking. The ancient Greeks believed that Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in mainland Greece, was the home of the gods.

Ancient Greek religious practice, essentially conservative in nature, was based on time-honored observances, many rooted in the Bronze Age (3000–1050 B.C.), or even earlier. Although the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer, believed to have been composed around the eighth century B.C., were powerful influences on Greek thought, the ancient Greeks had no single guiding work of scripture like the Jewish Torah, the Christian Bible, or the Muslim Qu’ran. Nor did they have a strict priestly caste. The relationship between human beings and deities was based on the concept of exchange: gods and goddesses were expected to give gifts. Votive offerings, which have been excavated from sanctuaries by the thousands, were a physical expression of thanks on the part of individual worshippers.

The Greeks worshipped in sanctuaries located, according to the nature of the particular deity, either within the city or in the countryside. A sanctuary was a well-defined sacred space set apart usually by an enclosure wall. This sacred precinct, also known as a temenos, contained the temple with a monumental cult image of the deity, an outdoor altar, statues and votive offerings to the gods, and often features of landscape such as sacred trees or springs. Many temples benefited from their natural surroundings, which helped to express the character of the divinities. For instance, the temple at Sounion dedicated to Poseidon, god of the sea, commands a spectacular view of the water on three sides, and the Parthenon on the rocky Athenian Akropolis celebrates the indomitable might of the goddess Athena.

The central ritual act in ancient Greece was animal sacrifice, especially of oxen, goats, and sheep. Sacrifices took place within the sanctuary, usually at an altar in front of the temple, with the assembled participants consuming the entrails and meat of the victim. Liquid offerings, or libations ( 1979.11.15 ), were also commonly made. Religious festivals, literally feast days, filled the year. The four most famous festivals, each with its own procession, athletic competitions ( 14.130.12 ), and sacrifices, were held every four years at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. These Panhellenic festivals were attended by people from all over the Greek-speaking world. Many other festivals were celebrated locally, and in the case of mystery cults , such as the one at Eleusis near Athens, only initiates could participate.

Hemingway, Colette, and Seán Hemingway. “Greek Gods and Religious Practices.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grlg/hd_grlg.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth, eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary . 3d ed., rev. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Pedley, John Griffiths. Greek Art and Archaeology . 2d ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Pomeroy, Sarah B., et al. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Robertson, Martin. A History of Greek Art . 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

Additional Essays by Seán Hemingway

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Greek Hydriai (Water Jars) and Their Artistic Decoration .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Hellenistic Jewelry .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Intellectual Pursuits of the Hellenistic Age .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Mycenaean Civilization .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Africans in Ancient Greek Art .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.) .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Athletics in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ The Rise of Macedon and the Conquests of Alexander the Great .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ The Technique of Bronze Statuary in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Cyprus—Island of Copper .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Music in Ancient Greece .” (October 2001)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Etruscan Art .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Prehistoric Cypriot Art and Culture .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Seán. “ Minoan Crete .” (October 2002)

Additional Essays by Colette Hemingway

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Greek Hydriai (Water Jars) and Their Artistic Decoration .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Hellenistic Jewelry .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Intellectual Pursuits of the Hellenistic Age .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Mycenaean Civilization .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Retrospective Styles in Greek and Roman Sculpture .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Africans in Ancient Greek Art .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Architecture in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.) .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Labors of Herakles .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Athletics in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Rise of Macedon and the Conquests of Alexander the Great .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Technique of Bronze Statuary in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Women in Classical Greece .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Cyprus—Island of Copper .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Music in Ancient Greece .” (October 2001)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) and Art .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Etruscan Art .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Prehistoric Cypriot Art and Culture .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Sardis .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Medicine in Classical Antiquity .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Southern Italian Vase Painting .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Theater in Ancient Greece .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Kithara in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Minoan Crete .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.)

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece

- Music in Ancient Greece

- Theater in Ancient Greece

- Africans in Ancient Greek Art

- Architecture in Ancient Greece

- Early Cycladic Art and Culture

- Eastern Religions in the Roman World

- Etruscan Language and Inscriptions

- Greek Hydriai (Water Jars) and Their Artistic Decoration

- Greek Terracotta Figurines with Articulated Limbs

- The Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 B.C.–68 A.D.)

- The Labors of Herakles

- Medicine in Classical Antiquity

- Medusa in Ancient Greek Art

- Mystery Cults in the Greek and Roman World

- Retrospective Styles in Greek and Roman Sculpture

- The Roman Banquet

- Roman Sarcophagi

- Southern Italian Vase Painting

- The Symposium in Ancient Greece

- Time of Day on Painted Athenian Vases

- Women in Classical Greece

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of the Ancient Greek World

- List of Rulers of the Roman Empire

- Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Ancient Greece, 1–500 A.D.

- Southern Europe, 2000–1000 B.C.

- Southern Europe, 8000–2000 B.C.

- 10th Century B.C.

- 1st Century B.C.

- 2nd Century B.C.

- 2nd Millennium B.C.

- 3rd Century B.C.

- 3rd Millennium B.C.

- 4th Century B.C.

- 5th Century B.C.

- 6th Century B.C.

- 7th Century B.C.

- 8th Century B.C.

- 9th Century B.C.

- Ancient Greek Art

- Aphrodite / Venus

- Archaic Period

- Ares / Mars

- Artemis / Diana

- Athena / Minerva

- Balkan Peninsula

- Classical Period

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Dionysus / Bacchus

- Eros / Cupid

- Geometric Period

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- Greek Literature / Poetry

- Herakles / Hercules

- Hermes / Mercury

- Homer’s Iliad

- Homer’s Odyssey

- Literature / Poetry

- Musical Instrument

- Mycenaean Art

- Mythical Creature

- Nike / Victory

- Plucked String Instrument

- Poseidon / Neptune

- Religious Art

- Satyr / Faun

- String Instrument

- Zeus / Jupiter

Artist or Maker

- Achilles Painter

- Amasis Painter

- Andokides Painter

- Euphiletos Painter

- Kleophrades Painter

- Lysippides Painter

- Meidias Painter

- Menelaos Painter

- Nikon Painter

- Phiale Painter

- Sabouroff Painter

- Tithonos Painter

- Villa Giulia Painter

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Enamored” by Seán Hemingway

- Connections: “Motherhood” by Jean Sorabella

- Connections: “Olympians” by Gwen Roginsky and Ana Sofia Meneses

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)