Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence Research Paper

Introduction, scope of work place violence, causes of violence in the work place, impacts of workplace violence, implication of workplace violence in managing human resources, implementation of the hr plan, works cited.

Work place violence can be defined as violence caused by employees on their fellow employees or vive versa. It may include abuses, threats, intimidation, and physical abuse among others. Work place violence is a serious issue that can even lead to a reduction in production in an organization. It also results in increased costs especially when physical violence is used.

Normally, a work place is supposed to be a place where people from diverse geographical areas converge to meet the specific needs of an organization. This is a place where we expect to find peace and tight safety measures because the people employed are actually working to earn a profit.

However, this is not always the case and most of the times some cases of violence are reported. In every organization we have employees who never feel satisfied with what they do or get and will constantly involve themselves in gossiping their fellow workers or the employer. This amounts to violence because such things can get to the person in question and they may cause him distress.

Work place violence is a serious offense that is punishable by law. If the organization is reported to have been abusing the employees, it is liable to pay certain fines and may be forced to compensate the person being abused. There are various types of work place violence which include but not limited to physical abuse, intimidation, threats or abuse, and the use of more aggravated weapons such as knives, furniture, guns among others.

Physical violence is the use of force on someone else it may include kicks, punishments, or slaps. Most violence cases in the work place increase the costs that an organization incurs because of paying medical bills and fines although some costs are indirect for instance destruction of the organization’s image among others.

This paper will look at some of the causes of work place violence, the impacts it has on the performance of industries, and its impacts to the management of human resources. It will go further to include a HR plan that can be used to address this problem and conclude by giving recommendations for the implementation and management of the proposed HR plan.

Work place violence is a problem that is present in almost all industries. It does not affect specific industries but is a common issue in almost every work place. However, the extent of violence differs from one industry to the other because there are some industries with tight security measures and it would be very easy to stop violence because if aggravates.

In other industries, employees have been ignored and few are the times when the employer seems to care about what actually goes on in the workplace. it is worth noting that, it is the responsibility of every employer to ensure that employees are provided with a secure working environment.

This includes providing them with necessary training on safety so that they are able to take care of themselves (King 10). Failing to train employees on safety measures amounts to workplace violence and an employee who has been denied this has a right to sue the employer if something bad happens to him while in the course of carrying out his daily responsibility.

But the question is how man industries provide their employees with the necessary training on safety before they commence their duties? The answer is, very few of the industries we have actually enlighten their employees on such issues. This kind of work place violence is referred to as negligence.

We have witnessed a number of industries where the employers are the ones who abuse the innocent employees. This includes government institutions where employees are forced to have sexual intimacy with their bosses if they want to retain their positions. Others have to part with a certain amount of money if they are to receive promotions.

Corruption has increased in the work place and people who deserve to be rewarded are not, but instead these rewards go to employees who do deserve. In other places, employees are exploited by their employers where they are required to work for many hours with no payment of overtime. Most of these companies are private entities where employees are threatened in case they try to sue the company (King 10).

It is not only employers who cause violence on the employees but fellow employees also cause violence on other employees. This mostly occurs if the employee causing violence is in a high position in the organizational structure. These are the employees who misuse their position to intimidate, abuse, or even threaten other employees.

In some cases, they force their subordinates to perform duties that they have not been assigned. Others are abused physically if they refuse to oblige to their request. The abused employees may fail to report such instances because they fear losing their jobs.

There are many reasons that can trigger employees or employers to cause violence on other employees. This includes anger, hatred, and grudges, among others. The causes of violence can be well understood through analyzing the common types of violence in the work place. There are mainly four types of work place violence; criminal violence, service user violence, worker-on-worker violence, and domestic violence. Criminal violence is caused by individuals or groups of people who do not have a direct relationship with the organization (Bensimon 26).

The main aim of this kind of violence would be to steal cash, stocks of other properties in the premises of the organization. While this is taken place, employees may be injured trying to protect the organization’s property while others may even be killed if they fail to comply with the criminals instructions.

The other type of violence; service user violence is also caused by individuals or groups of people who do not have a direct relationship with the organization but are in one way or the other indirectly related to it. This includes customers or other service users who consume the products or services of a certain organization.

These people many cause violence if they are frustrated with the organization’s products/services or if they feel as if their grievances are ignored or there are given substandard services. Worker-on-worker violence can be caused by grudges, hatred, or can be caused by an employee who feels that he has received unjust disciplinary actions. In other cases, it can be a protest to imposed redundancy.

Last but not least, domestic violence is caused by persons who are not employees or employers in a certain organization but are in one way or the other related to employees who work for the organization this includes spouses, partners, or friends. This kind of violence can be caused by family disagreements and it is perpetrated in the work place simply because the wrongdoer has knowledge of the place where the targeted individual is at that particular time (VanBuren, Anderson and Sabatelli 480).

The results of work place violence can be detrimental to an organization since they increase costs and cause a reduction in performance. Most of this violence reduces the morale of workers and their motivation to work reduces. It may cause death of some employees, others may be become disabled as a result of physical violence.

It can even cause a lot of pain and distress on employees who may feel frustrated with their work and start looking for other places. The result of this is poor performance both on the side of the employee and the organization. To some extent, workplace violence can be an increased cost to an organization in terms of increased rates of absenteeism.

As violence increases, the work place becomes an unsafe place for many workers who may opt to absent themselves from job rather than face the frustrations that present themselves every day (VanBuren, Anderson and Sabatelli 471).Others may take the option of sick leaves even when they are of sound health. The organization has to incur increased insurance costs, medical bills or even pay fines if the abused sue it in court.

Work place violence may also cause an increase in employee turn over, requiring the organization to incur additional costs every now and then while looking for other employees. The recruitment and selection process is not only expensive but can result in reduced sales revenue because of the appointment of unskilled workers.

Human Resource Management is an indispensable element in the performance of a corporate organization and works together with other departments to achieve the organization’s goals.

There are certain agencies that are required to create and maintain a workplace that is free from the threat of violence. This is done through the development of policies and procedures which should be implemented in the work places through the human resource department.. These policies expect the agency to;

- Communicate a policy statement that prohibits workplace violence

- Appoint a coordinator who is responsible for overseeing that workplace prevention programs are implemented

Develop and implement a crisis management plan

- protect employees who might be victims of violence

- Establish a mechanism that would allow employees to report any case of violence

- Train managers and supervisors on how to identity a condition that can lead to violence and how to address such a situation

On the other hand the human resources department is responsible for providing regular training on workplace violence prevention and management and assists agencies in developing and implementing workplace violence programs and plans. It is worth noting that, the main function of the human resource department is to prevent workplace violence and at the same time, this is the department that is the main target of threats of workplace violence (Bensimon 26).

Human resource planning involves analysis of skills of current workforce, forecasting manpower, and being responsive of customers demand. Human resource planning is important in every organization because it helps the top management to view HR practices in relation to business decision. Human resources become cheaper because HRM can foresee future problems and solve them before they become uncontrollable

To address the issue of workplace violence, I will create a plan which I think should be adopted by all organizations. The purpose of this plan is to prevent workplace violence from occurring and it also outlines the process that should be followed if cases of violence are reported. It is the responsibility of all employees to refrain themselves from cases of violence although they are instances when violence occurs with having intended to do so. This plan has various departments as named below:

- Workplace violence prevention team- this team is made up of a group of employees and serves as a sub committee in the prevention of workplace violence. This team is composed of the director of safety and security, human resources manager and other senior staff. The main purpose of this team is to carry out regular reviews related to workplace violence and provide recommendations on the training or education programs that should be adopted to prevent the problem

- Safety and security office-This office is responsible for receiving all complaints related to workplace violence and respond to the same in a prompt manner. It also has a duty of maintaining all records of violence.

- Human resources office- This office is responsible for providing training to managers and supervisors on topics such as conflict resolution, teamwork, and discipline. It is also responsible for offering training and educational awareness to the other members of staff on ways of preventing violence, respond to violence and the importance of team work (Kirk and Franklin 523).

- Supervisors- It is the responsibility of supervisors to ensure that, employees are provided with a secure working environment. In case of threats or incidents of violence, supervisors are supposed to notify the safety and security office so that prompt measures are taken.

- Employee assistance- An employee assistance program should be put in place to ensure that, employees’ needs, grievances, and request are met at all times. They should so be provided with training of how to respond to anger, resolve conflicts, among other things (Kirk and Franklin 523).

The purpose of this plan is to ensure that, Workplace violence is prevented, all complaints of violence are addressed promptly and to provide employees with a safe working condition.

By providing the supervisors, managers, and employees with training and education awareness on workplace violence, they become more responsible and cases of violence reduces.

To ensure that the plan is properly implemented I would recommend the workplace violence team, safety and security office and the human resources office to work in coordination in providing training to all employees, in ensuring that education and awareness is provided to all members of staff, including the support staff.

All cases of violence should be reported to the safety and security office and more severe cases reported to the nearest local authority. The office of safety and security should carryout investigation to ascertain the causes of violence and the human resources office should be informed of the same so that appropriate disciplinary actions are taken.

The safety and security office should then go ahead and file all cases of violence for reference in future. This plan should be included in Employee orientation handbook and in annual security reports for awareness and proper monitoring.

Bensimon, Helen Frank. Violence in the Work place. Training & Development, January 1994, Vol. 48 Issue 1 P26,

King, Robert O. Work place violence: A growing liability for employers. South Carolina Business journal, November 1994, Vol. 13 Issue 10, p10

Kirk, Delaney J. and Franklin, Geralyn Mcclure. “Violence in the Workplace: Guidance and Training Advice for Business Owners and Managers”, Business and Society Review 2003 108: p523

VanBuren, Trachtenberg Jennifer; Anderson Stephen and Sabatelli, Ronald. Work-home conflict and domestic violence: A test of a conceptual model. Journal of family violence, October 2009, Vol. 24 Issue 7 P471-483

- Sexual Harassment at the Workplace

- Safety in the Military Workplace

- Human Resource Management. Workplace Violence

- Best Practice Manual for Supervisors

- Effective and Ineffective Supervisor

- Discrimination Remedy at Workplace: Affirmative Action Programs, Reverse Discrimination and Comparable Worth

- Market Research of Thomas Sabo

- Maintenance and Engineering Department for Wayward Hotel

- Practices for Improving Employees Performance

- Managing Creative Project and Team

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 16). Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence. https://ivypanda.com/essays/work-place-violence/

"Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence." IvyPanda , 16 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/work-place-violence/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence'. 16 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence." May 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/work-place-violence/.

1. IvyPanda . "Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence." May 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/work-place-violence/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Addressing the Causes and Effects of Workplace Violence." May 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/work-place-violence/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Contemporary evidence of workplace violence against the primary healthcare workforce worldwide: a systematic review

Hanizah mohd yusoff, hanis ahmad, halim ismail, naiemy reffin, faridah kusnin, nazaruddin bahari, hafiz baharudin, huam zhe shen, maisarah abdul rahman.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2023 Jun 23; Accepted 2023 Oct 2; Collection date 2023.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Violence against healthcare workers recently became a growing public health concern and has been intensively investigated, particularly in the tertiary setting. Nevertheless, little is known of workplace violence against healthcare workers in the primary setting. Given the nature of primary healthcare, which delivers essential healthcare services to the community, many primary healthcare workers are vulnerable to violent events. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, the number of epidemiological studies on workplace violence against primary healthcare workers has increased globally. Nevertheless, a comprehensive review summarising the significant results from previous studies has not been published. Thus, this systematic review was conducted to collect and analyse recent evidence from previous workplace violence studies in primary healthcare settings. Eligible articles published in 2013–2023 were searched from the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed literature databases. Of 23 included studies, 16 were quantitative, four were qualitative, and three were mixed method. The extracted information was analysed and grouped into four main themes: prevalence and typology, predisposing factors, implications, and coping mechanisms or preventive measures. The prevalence of violence ranged from 45.6% to 90%. The most commonly reported form of violence was verbal abuse (46.9–90.3%), while the least commonly reported was sexual assault (2–17%). Most primary healthcare workers were at higher risk of patient- and family-perpetrated violence (Type II). Three sub-themes of predisposing factors were identified: individual factors (victims’ and perpetrators’ characteristics), community or geographical factors, and workplace factors. There were considerable negative consequences of violence on both the victims and organisations. Under-reporting remained the key issue, which was mainly due to the negative perception of the effectiveness of existing workplace policies for managing violence. Workplace violence is a complex issue that indicates a need for more serious consideration of a resolution on par with that in other healthcare settings. Several research gaps and limitations require additional rigorous analytical and interventional research. Information pertaining to violent events must be comprehensively collected to delineate the complete scope of the issue and formulate prevention strategies based on potentially modifiable risk factors to minimise the negative implications caused by workplace violence.

Introduction

Events where healthcare workers (HCWs) are attacked, threatened, or abused during work-related situations and that present a direct or indirect threat to their security and well-being are referred to as workplace violence (WPV) [ 1 ]. Violence in the health sector has increased over the last decade and is a primary global concern [ 2 ]. Recent statistical data demonstrated that HCWs were five times more likely to experience violence than workers in other sectors and are involved in 73% of all nonfatal violent work incidents [ 3 ]. The experience of WPV is linked to reduced quality of life and negative psychological implications, such as low self-esteem, increased anxiety, and stress [ 4 – 6 ]. WPV is often linked to poor work performance caused by lower job satisfaction, higher absenteeism, and reduced worker retention [ 7 , 8 ], which may disrupt patient care quality and other healthcare service productivity [ 9 ]. Decision-makers and academics worldwide now recognise the seriousness of WPV in the health sector, which has been extensively examined in tertiary settings, particularly emergency and psychiatric departments. Nonetheless, understanding of WPV in primary healthcare (PHC) settings is minimal.

The modern health system has experienced a fundamental shift in delivery systems while moving towards universal health coverage and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [ 7 ]. Despite the focus on tertiary-level individual disease management, the healthcare system recently moved towards empowering primary-level patient and community health needs [ 10 ]. Robust PHC system delivery provides deinstitutionalised patient care, which includes health promotion, acute disease management, rehabilitation, and palliative services, via primary health units in the community, which are referred to with different terms across countries, such as family health units, family medicine and community centres, and outpatient physician clinics [ 11 – 13 ]. In developing and developed countries, PHC services are associated with improved accessibility, improved health conditions, reduced hospitalisation rates, and fewer emergency department visits [ 14 ]. The backbone of this health system delivery is a PHC team of family physicians, physician assistants, nurses, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, social workers, administrative staff, auxiliaries, and community workers [ 15 ].

Nevertheless, the nature of PHC service, which delivers essential services to the community, requires direct interaction with patients and family members, thus increasing the likelihood of experiencing violent behaviour [ 10 ]. Understaffing occurs mainly due to the lack of comprehensive national data that could offer a complete view of the PHC workforce constitution and distribution, which results in increased responsibilities and compromised patient communication [ 15 ]. Considering the current worldwide employment patterns, a shortage of approximately 14.5 million health workers in 2030 is anticipated based on the threshold of human resource needs related to the SDG health targets [ 16 ]. Other challenges at the PHC level recently have also been addressed, including long waiting times, dissatisfaction with referral systems, high burnout rates, and limited accessibility in rural areas, which exacerbate existing WPV issues [ 14 ].

As PHC system quality relies entirely on its workers, the issue of WPV requires more attention. WPV issues must be examined separately between PHC and other clinical settings to support an effective violence prevention strategy for PHC, given that the violence characteristics and other relevant factors can vary by facility type. In addition, PHC workers also have distinct services, work tasks, and work environments [ 11 ]. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, interest in conducting empirical studies investigating WPV in the PHC setting has increased worldwide [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive systematic review summarising the results from previous studies has never been published. Understanding this issue among workers who serve under a robust PHC system would be equally essential and requires attention to critical dimensions on par with WPV incidents in other clinical settings, especially hospitals. Therefore, this preliminary systematic review of WPV against the PHC workforce analysed and summarised the current information, including the WPV prevalence, predisposing factors, implications, and preventive measures in previous research.

Literature sources

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 review protocol [ 18 ]. A comprehensive database search of the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases was conducted in February 2023 using key terms related to WPV (“violence”, “harassment”, “abuse”, “conflict”, “confrontation”, and “assault”), workplace setting (“primary healthcare”, “primary care”, “community unit”, “family care”, “general practice”), and victims (“healthcare personnel”, “healthcare provider”, “medical staff”, “healthcare worker”). The keywords were combined using advanced field code searching (TITLE–ABS–KEY), phrase searching, truncation, and the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND”.

Eligibility criteria

All selected studies were original articles written in English and published within the last 10 years (2013–2023) on optimal sources or current literature. The articles were selected based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Described all violence typology (Types I–IV) and its form (verbal abuse, physical assault, physical threat, racism, bullying, or sexual assault);

The topic of interest concerned every category of PHC personnel (family doctor, general practitioner, nurse, pharmacist, administrative staff).

Exclusion criteria

The violence occurred in a tertiary or secondary setting (during training/industrial attachment at a hospital);

Case reports or series, and technical notes.

Study selection and data extraction

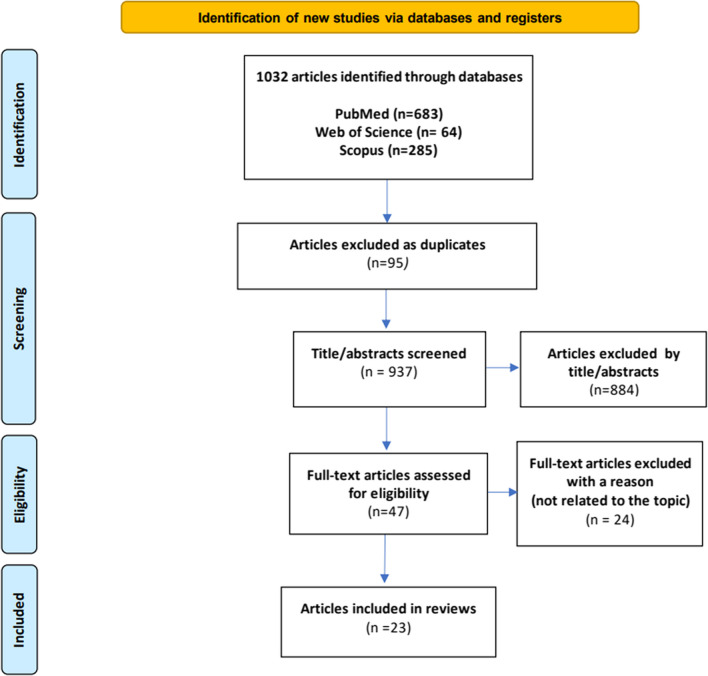

All research team members were involved in screening the titles and abstracts of all articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All potentially eligible articles were retained to evaluate the full text, which was conducted interchangeably by two teams of four members. Differences in opinion were resolved with the research team leader’s input. Before the data extraction and analysis, the methodological quality of the finalised article was assessed using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Based on the outcomes of interest, the information obtained from the included articles was compiled in Excel and grouped into the following categories: (i) prevalence, typology, and form of violence, (ii) predisposing factors, (iii) implications, and (iv) preventive measures. Figure 1 depicts the article selection process flow.

PRISMA flow diagram

General characteristics of the studies

Forty-three articles were potentially eligible for further consideration, but only 23 articles provided information that answered the research questions (Table 1 ) [ 13 , 19 – 40 ]. The studies mainly covered 16 countries across Asia, Europe, and North and South America, thus providing good ethnic or cultural background diversity. All included articles were observational studies. Sixteen studies were quantitative descriptive studies conducted through self-administered surveys using different validated local versions of WPV study tools (response rate: 59–94.47%). Four qualitative studies collected data through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The remaining studies were mixed-method studies that combined quantitative and qualitative research elements. Of the 23 studies, 15 involved various categories of healthcare personnel, seven involved primary clinicians, and one involved pharmacist.

General characteristic of studies

Prevalence, typology, and form of violence

14 studies focused on the prevalence of patient- or family-perpetrated violence (Type II), three studies focused on co-worker-perpetrated violence (Type III), while six studies reported on both type II and III violence (Table 2 ). Evidence of domestic- and crime-type violence (Types I and IV) was not found in the literature. In most studies, the primary outcome was determined based on recall incidents over the previous 12 months. The reported prevalence of violence against was 45.6–90%. The incidence rate of verbal abuse was 46.9–90.3%, which rendered it the most commonly identified form of violence, followed by threats or assault (13–44%), bullying (19–27%), physical assault (15.9–20.6%), and sexual harassment (2–17%). The reported prevalence of violence against doctors was 14.0–73.0%, followed by that against nurses (6.0–48.5%), pharmacists (61.8%), and others (from 40% to < 5%). Patients and their families were the main perpetrators of violence, followed by co-workers or supervisors (Table 2 ).

The prevalence, typology, and form of WPV against primary healthcare workers

Predisposing factors of WPV

Victims’ personal characteristics

Several socio-demographic factors were identified as predictors of WPV. Male gender and female gender were associated with risk of physical violence [ 21 – 23 ] and non-physical violence [ 12 , 19 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 39 ], respectively. Nevertheless, a specific form of non-physical violence, such as coercion, was also reported less frequently among women [ 34 ]. A minority group of HCWs with individual sexual identities perceived a severe form of intra-profession violence, such as threats to their licenses [ 24 ]. Being young presented a higher risk for violence, especially sexual harassment, and was frequently complicated by physical injury [ 23 , 27 , 34 ]. A personality trait study demonstrated a significant association between aggression incidents with “reserved” and “careless” personality types [ 20 ]. Regarding professional background, medical workers were more vulnerable to physical violence compared to non-medical workers [ 12 , 22 , 34 ]. Nurses faced a higher risk of WPV than others [ 19 , 23 , 27 , 37 ]. Nevertheless, non-medical staff were also vulnerable to physical violence [ 35 ]. Due to less work experience, certain HCWs were identified as vulnerable to violence [ 22 , 26 , 35 ]. Furthermore, violent clinic incidents could occur due to poor professional–client relationships triggered by workers’ attitudes, such as a lack of communication and problem-solving skills [ 25 , 26 ] (Table 3 ).

Perpetrators’ personal characteristics

Predisposing factors, impact, and coping mechanisms regarding WPV among primary healthcare workers

Patients and their family members mainly triggered WPV, and some exhibited aggressive behaviours, such as psychiatric disorders or drug influence [ 20 , 23 , 28 ]. Female patients in a particular age group were noted as being at risk of causing both physical and non-physical violence [ 34 ]. WPV was also prevalent in clinics, which was attributable to poor patient–professional relationships triggered by the perpetrator’s inappropriate attitude, such as being excessively demanding, or when clients did not fully understand the role of HCWs or used PHC services for malingering [ 25 , 26 , 31 ] (Table 3 ).

Community/Geographical factors

We identified the role of the local community, where WPV was prevalent among HCWs who served at PHC facilities in drug trafficking areas [ 27 ] and that were surrounded by a population of lower socio-economic status [ 28 ]. Furthermore, WPV was increased in clinics in urban and larger districts, which have a lower HCW density per a given population compared to the national threshold of human resource requirement [ 29 , 32 , 39 ], whereas WPV reduced in rural areas, where medical service was perceived more accessible due to lower population density [ 39 ] (Table 3 ).

Workplace factors

The operational service, healthcare system delivery, and organisational factors were identified as the three major sub-themes of work-related predictors of WPV. Specific operational services increased the likelihood of WPV, for example, during home visit activities, handling preschool students, dealing with clients at the counter, and triaging emergency cases [ 27 , 36 – 39 ]. WPV was more prevalent if the service was delivered by HCWs who worked extra hours with multiple shifts, particularly during the evening and night shifts [ 30 , 36 , 37 , 39 ]. HCWs who worked in clinics with poor healthcare delivery systems due to ineffective appointment systems, uncertainty of service or waiting times, and inadequate staffing [ 25 – 27 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 ] faced higher potential exposure to aggressive events compared to those working in clinics with better systems. WPV was also linked to a lack of organisational support, mainly in fulfilling workers’ needs, such as providing sufficient human resources, capital, and on-job training, or equal pay schedule and job task distribution, or ensuring a safety climate and clear policy for WPV management [ 22 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 35 – 37 ]. We also determined that the lack of a multidisciplinary work team and devalued family medicine speciality by other specialists caused many HCWs to remain in poor intra- or inter-profession relationships and be vulnerable to co-worker-perpetrated incidents in PHC settings [ 24 , 26 , 33 , 39 ] (Table 3 ).

Effects of WPV

The most frequently reported implications by the victims of WPV involved their professional life, where most studies mentioned reduced performance, absenteeism, the decision to change practice, and feeling dissatisfied or overlooked in their roles. This was followed by poor psychological well-being (anxiety, stress, or burnout), and emotional effects (feeling guilty, ashamed, and punished) [ 13 , 21 , 24 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Three studies reported on physical injuries [ 13 , 21 , 34 ], while only one study reported a deficit in victims’ cognitive function, which might lead to near-miss events involving patients’ safety elements, and social function defects, where some victims refused to deal with patients in the future [ 31 ]. Only one study reported the WPV implication of being environmentally damaged [ 34 ] (Table 3 ).

Victims’ coping mechanisms and organisational interventions

The coping strategies adopted by HCWs varied depending on the timing of the violent events. Safety approaches such as carrying a personal alarm, bearing a chevron, and other similar steps were used, especially by female HCWs, as a proactive coping measure against potentially hazardous incidents [ 21 ]. “During an aggressive situation triggered by patients, certain workers used non-technical skills, which included leadership, task management, situational awareness, and decision-making [ 31 ]. During inter-professional conflict (physician–nurse conflict), the most predominant conflict resolution styles were compromise and avoiding, followed by accommodating, collaborating, and competing [ 40 ]. Avoiding conflict resolution was most common among nurses, whereas compromise was most common among doctors [ 40 ]. Post-violent event, most HCWs chose to take no action, while some utilised a formal reporting channel either via their supervisors, higher managers, police officers, or legal prosecution. Some HCWs also utilised informal channels by sharing problems with their social network members, such as colleagues, friends, or family members [ 13 , 30 , 36 , 39 ]. Only one article mentioned health managers’ organisational preventive interventions, which included internal workplace rotation, staff replacement, and writing formal explanation letters [ 34 ] (Table 3 ).

We analysed the global prevalence and other vital information on WPV against HCWs who serve in the PHC setting. We identified noteworthy findings not reported in earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses, where the healthcare setting type was not taken into primary consideration [ 2 , 41 – 49 ].

Determining a definite judgement on WPV incidence against PHC workers worldwide is challenging, given that several of the studies selected for analysis were conducted using convenience sampling with low response rates. Nevertheless, notable results were obtained. WPV prevalence varied significantly, where the highest prevalence was reported in Germany (91%) and the lowest was reported in China (14%). Based on the average 1-year prevalence rate of WPV, we determined that the European and American regions had a greater WPV prevalence than others, which was consistent with a recent meta-analysis [ 50 ]. One reason might be the more effective reporting system in these regions, which facilitate more reports through a formal channel, as mentioned previously [ 51 ]. Contrastingly, opposite circumstances might cause WPV events to go unreported in other parts of the world. We also revealed a need for more evidence on WPV in the PHC context in Southeast–East Asia and African regions. The number of peer-reviewed articles from these regions could have been much higher, which inferred that the issue in these continents still requires resolution.

Various incidents of violence, including those of a criminal or domestic nature, commonly occur in the tertiary setting. The Healthcare Crime Survey by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) reported that within a 10-year period (2010–2022), the number of hospital workers who experienced ten types of crime-related events in the workplace, such as murder, rape, robbery, burglary, theft (Type I), increased by the year [ 52 ]. In contrast, most studies conducted in PHC settings focused on providing more evidence of Type II violence, whereby other types (I and IV) were rarely detected. The scarcity of evidence does not necessarily indicate that PHC workers are not vulnerable to criminal or domestic violence. Rather, it implies that WPV is still not entirely explored in the PHC setting, which undermines the establishment of a comprehensive violence prevention strategy that encompasses all types of violence [ 53 ].

Hospital-based studies reported diverse forms of violence, where both physical and verbal violence were dominant [ 47 , 54 – 56 ]. Violence as a whole and physical violence in particular tend to occur in nursing homes and certain hospital departments, such as the psychiatric department, emergency rooms, and geriatric nursing units [ 47 , 55 , 56 ]. Volatile individuals with serious medical conditions or psychiatric issues or who are under the influence of drugs or alcohol were mainly responsible for this severe physical aggression [ 53 ]. Similar to previous hospital-based studies, diverse forms of violence (verbal abuse, physical attacks, bullying, sexual-based violence, psychological abuse) were recorded in PHC settings. Despite this, most of the studies determined that the perpetrators’ disparate characteristics resulted in more frequent documentation of verbal violence than physical violence. Dissatisfied patients or family members were more likely to perpetrate greater incidents of verbal abuse [ 25 , 26 , 31 ], either due to their medical conditions or dissatisfaction with the services provided [ 30 ]. This noteworthy discovery prompted new ideas, indicating that variance in the form of violence might also be determined by the healthcare setting role [ 57 ].

Our findings demonstrated that sexual-based violence was the least frequently documented form of violence, with a regional differences pattern indicating relatively lower sexual-based violence reporting in the Middle Eastern region [ 13 , 30 ]. This result contrasted with a previous systematic review of African countries that reported that sexual-based violence was one of the dominant forms of WPV. This lower incidence was possibly due to under-reporting by female employees who were reluctant to report sexual harassment aggravated by cultural sensitivities regarding sexual assault exposure [ 58 ]. Such culturally driven decision-making practices are worrying, as they could lead to underestimation of the true extent of the issues and cause more humiliating incidents and the lack of a proper response.

We identified considerable numbers of significant predisposing factors, which were determined via advanced multivariate modelling. Most factors were comparable with that in previous WPV research, especially those related to the victims’ individual socio-demographic and professional backgrounds [ 2 , 41 , 42 ]. Several studies consistently reported that nurses were vulnerable to WPV compared to physicians and others, which was supported by numerous prior systematic studies [ 19 , 23 , 27 , 37 ]. This could be explained by the accessible nature of nurses as healthcare professionals to patients and families [ 50 ]. Furthermore, nurses interact first-hand with clients during treatment, rendering them more likely to become the initial victims of WPV before others. Nevertheless, this result should not necessarily suggest that other professions are not at risk for violence. Due to the shortage of evidence regarding the remaining category of PHC workers, it is impossible to provide a more conclusive and realistic assessment of the above.

The results demonstrated that many PHC clinics were built in community areas with a variety of settings, such as high-density commercial developments in urban or rural areas, resource-limited locations, or areas with a high crime concentration [ 27 – 29 , 32 , 39 ]. Therefore, an additional new sub-theme under predisposing factors, namely, “community and geographical factors”, was created to include all evidence on the relationship between WPV vulnerability and community social character and geo-spatial factors. Although several hospital-based studies deemed this topic less significant, several studies in the present review that examined the relationship between geographic information and the surrounding population characteristics with WPV reported valuable and constructive information for PHC prevention framework efforts.

In general, we identified a similar correlation between work-related factors and WPV as in hospital-based studies, particularly on healthcare system delivery and organisational support elements [ 40 – 48 ]. Nonetheless, the evidence on operational service was vastly distinct. As several PHC services are expanded outside facilities, there is increased potential for violence against HCWs when they provide out of clinic services, for example, during home visits and school health services [ 21 , 37 , 39 ]. Such situations might require more comprehensive prevention measures compared to violent events that occur within health facilities. Unfortunately, the available literature that describes and assesses the safety elements of HCWs in PHC settings mainly focused on services inside the health facilities, indicating that WPV prevention and management should be expanded to outdoor services [ 21 ].

The studies included in this review comprehensively described the observed implications on WPV victims in PHC settings. Nonetheless, additional vital information on the adverse effects on organisational elements remains lacking, especially regarding the quality of patient care involving potential near-miss events, negligence, and reduced safety elements [ 31 ]. The economic effect is another important aspect that requires further consideration. Recent financial expense data were only available from hospital-based research. A systematic review revealed that WPV events resulting in 3757 days of absence at one hospital over 1–3 years involved a cost exceeding USD 1.3 billion that was mainly due to reduced productivity [ 43 ].

The magnitude of under-reporting among HCWs was concerning, as most respondents admitted that they declined to report WPV cases through formal reporting channels, such as via electronic notification systems, supervisors, or police officers [ 13 , 30 , 36 , 39 ]. Although the included articles mentioned several impediments to reporting, such as fear of retaliation, fear of missing one’s job, and feelings of regret and humiliation, [ 13 , 30 , 36 ], the main reason for under-reporting was a lack of trust in existing WPV preventive institutional policies. Most respondents perceived that reporting the case would not lead to positive changes and were dissatisfied with how the policy was administered [ 13 , 30 ]. Despite much evidence on proactive coping mechanisms utilised by the HCWs, which were either behaviour change technique or conflict resolution style, we did not obtain additional crucial information on existing regional WPV policies or specific intervention frameworks at institutional level [ 31 , 40 ]. Furthermore, reports of the mediating functions of federal- or state-level central funding and legal acts or regulatory support in establishing effective regional violence policies were also absent in primary settings. Further discussion in this area is crucial as significant federal or state government support would improve HCWs’ perceptions of regional prevention program and would potentially reduce the rate of violence against HCWs.

Opportunities for future research

Only a few studies discussing WPV in the PHC setting have been published over the 10 years covered in this review. Local researchers and stakeholders should define and prioritise important areas of study. Given the heterogeneity of the forms of violence, it might be advantageous to conduct additional observational research in the future to describe the situation and investigate the associations between the rate of violence and its multiple predictors using Poisson regression analysis [ 59 ]. At the present stage, quasi-experimental evidence is ambitious. Therefore, more longitudinal studies are required to evaluate the efficacy of any newly introduced violence prevention and management measures designed in primary healthcare settings [ 60 ].

A comprehensive investigation of WPV occurrences beyond Type II violence is required to accurately reflect the breadth of the issue and focus on prevention efforts. In the present study, the association pattern between the consequences of WPV for specific perpetrators was not investigated as in prior research due to the scarcity of evidence on Type I, III, and IV violence. For example, Nowrouzi-Kia et al. revealed that the victims of inter-professional perpetuation (Type III) experienced more severe consequences involving their professional life (low job satisfaction, increased intention to quit) than those who experienced patient or family-perpetrated violence (Type II), which involved psychological and emotional changes [ 61 , 62 ]. In addition, the study scope must also be expanded to include assaults against both healthcare personnel and patients in primary settings. A hospital-based investigation by Staggs 2015 revealed a significant association between the number of staff at psychiatric patient units and the frequency of violent incidents. Surprisingly, this rigorous investigation determined that higher levels of hospital staffing of registered nurses were associated with a higher assault rate against hospital staff and a lower assault rate against patients [ 63 ].

Despite universal exposure to WPV, the incidence rates and types of violence vary between regions. Thus, the primary investigation focus should be tailored to specific violence issues in a particular setting. Our results highlighted the need for further research into strengthening WPV policy, particularly concerning the reporting systems in regions outside European and American countries. Compared to other regions, local academicians in Southeast Asia and Africa are encouraged to increase their efforts to perform more epidemiological WPV studies in the future to better understand the WPV issue. It is crucial to identify the underlying causes of low prevalence of sexual harassment, particularly in the Middle East, which might be caused by under-reporting influenced by culture or gender bias. Although it is asserted that sexual-based violence is likely to occur commonly in cultures that foster beliefs of perceived male superiority and female social and cultural inferiority, the reported prevalence rate of such violence in certain regions [ 64 ], particularly in the Middle East, was low, possibly due to under-reporting. Thus, to address this persistent problem, the existing reporting mechanisms must be improved and sexual-based violence should be distinguished from other forms of violence to encourage more case reporting. Simultaneously, sexual-based violence should also be defined differently across countries and various social and cultural contexts to reduce impediments to reporting [ 64 ].

In existing studies, the main focus of work-related predisposing factors is based on superficial situational analysis, which is identified using the local version of the standard WPV instrument tool via a quantitative approach. Nevertheless, this weak evidence would not support a more effective preventive WPV framework. This issue should be addressed in more depth and involve psychosocial workplace elements that cover interpersonal interactions at work and individual work and its effects on employees, organisational conditions, and culture. Qualitative investigations that complement and contextualise quantitative findings is one means of obtaining a greater understanding and more viewpoints.

Implications of WPV policies

The results had major effects on WPV prevention and intervention policies in the PHC setting. The results highlighted the importance of enacting supportive organisational conditions, such as providing adequate staffing, adjusting working hours to acceptable shifts, or developing education and training programmes. As part of a holistic solution to violence, training programmes should focus on recognising early indicators of possible violence, assertiveness approaches, redirection strategies, and patient management protocols to mitigate negative effects on physical, psychological, and professional well-being. While previous WPV studies focused more on physical violence and inspired intervention efforts in many organisational settings, our results necessitate attention on non-physical forms of violence, which include verbal harassment, sexual misconduct, and intimidation. The increased potential of domestic- and crime-type violence in PHC settings necessitates expanded prevention programmes that address patients, visitors, healthcare providers, the surrounding community, and the general population.

Our results demonstrated that under-reporting of violent events remains a key issue, which is attributable to a lack of standardised WPV policies in many PHC settings. The initial action that should be implemented in accordance with human resource policy is to establish a system that renders it mandatory for victims, witnesses, and supervisors to report known instances of violence to HCWs. Unnecessary and redundant reporting processes can be reduced by an advanced system for rapidly recording WPV incidents, such as in hospital settings, where WPV is reported via a centralised electronic system. However, healthcare professional and organisational advocacy remains necessary. These parties must promote the value of routine procedures to ask employees about their encounters with patient violence and to foster an environment, where the organisation encourages reporting of violent incidents.

In addition to insufficient reporting, it is crucial to draw attention to the manner in which violent incident investigations are currently conducted in most workplaces. In reality, the incident reporting focuses on the violence itself and its superficial or circumstantial analysis, as opposed to an in-depth examination of the causes of violence, which are due to workplace psychosocial hazards, poor clinic environment, or poor customer service. For example, if any patient-inflicted violence occurred as a result of unsatisfactory conditions caused by poor clinic service, such as unnecessary delay, the tendency is to report on the perpetrator’s behaviour or on the violence itself rather than the unmet health service provision issue. In the long-term, however, the findings of such an investigation would not support the development of a violence prevention and management guideline, as it focuses on addressing aggressive patients rather than enhancing clinic service quality. Therefore, the relevant authorities should formulate a proper plan to improve the existing reporting and investigations mechanism to ensure that it is more comprehensive, structured, and detailed, either by providing proper training for the investigators or conducting institutional-level routine root cause analysis discussions, so that the violence hazard risk assessment can be framed effectively to resolve the antecedent factors in the future.

Nonetheless, there remains much room for primary-level improvement in WPV awareness and abilities. Reports on the mediating roles of federal- and state-level central funding and regulatory support for efficient local WPV policies at primary level have not been found. Therefore, more studies will be necessary to fill these gaps and concentrate on examining the relationship between regional WPV policies and national support. Possibly, more central funding and state regulation following new positive results can be made available to aid local preventive programs. A strong central financial support is essential to support regional preventive programmes, such as employing security guards, enhancing the physical security of health facilities buildings, and research grants. Awadalla and Roughton strongly suggested that adequate national-level financial support is one of the essential components of successful regional policies that would alter HCW perceptions [ 65 ]. In terms of law and regulation, for example, Ferris and Murphy firmly supported the role of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) via the issuance of the “Enforcement Procedures for Investigating or Inspecting Workplace Violence” instructions to institutional-level officers as one of the essential components of local WPV prevention strategies [ 66 ].

Study strength and limitations

The present study is a preliminary systematic review that explored evidence of WPV against all PHC workers in empirical studies worldwide. The breadth of the review was achieved by incorporating numerous peer-reviewed high-quality published studies, which enabled us to derive a solid conclusion. The approach relied on the authors’ prior knowledge of the study topic, the standard review technique, and specialised keywords.

It is also important to emphasise several potential limitations. First, recall bias was introduced in most studies as the authors used self-reporting to recall previous incidents either up to 12 months prior or after a lifetime. As most of the included studies involved small sample sizes, a few studies with low response rates restricted the generalisability of the findings. Several studies were descriptive and were cross-sectional; consequently, extra caution should be applied when making inferences pertaining to the risk factor interactions with violence. Variability in the instrument used, data collection and analysis methods, the notion of violence, and the general study objective might account for the heterogeneity across studies, which limited comparisons across studies. As PHC health system delivery between countries is described by different terms or names or might be identified by names besides those used in the present study, studies that use such terms might have been overlooked during the database search.

WPV in the PHC setting is a common and growing issue worldwide. Many PHC workers reported experiencing violence in recent years, strongly suggesting that violence is a well-recognised psychosocial hazard in PHC comparable to hospital settings. HCWs are highly susceptible to violence perpetrated by patients or their families, which results in considerable negative consequences. With various predisposing factors, this complex issue indicates a need for more serious consideration of a resolution on par with that in the tertiary setting. Several research gaps and limitations necessitate additional rigorous analytical and interventional research in the future. Information on violent events must be comprehensively collected to delineate the complete scope of the issue and formulate prevention strategies based on potentially modifiable risk factors. Thus, a new interventions framework to mitigate violent events and control their negative implications can be established. The results presented here were derived from literature on diverse cultures worldwide, and, therefore, can be used as a data reference for policymakers and academicians for future opportunities in the healthcare system field.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Dean of the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) School of Medicine for granting permission to publish this work. We also thank the head of the UKM Community Health Department and its staff for their excellent cooperation during this study.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualisation, methodology, extensive article search, critical review of articles, result synthesis, and original draft write-up. All authors have read and agreed to publish this version of the manuscript.

No funding was associated with the work featured in this article.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. ILO. Safe and healthy working environments free from violence and harassment. International Labour Organization. 2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/resources-library/publications/WCMS_751832/lang--en/index.htm

- 2. Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–937. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2019-105849. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. The Joint Commission. Workplace Violence Prevention Standards. 2021;(30):1–6. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/workplace-violence-prevention ; https://iahssf.org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-Threat-Assessment-Strategies-to-

- 4. Yang BX, Stone TE, Petrini MA, Morris DL. Incidence, type, related factors, and effect of workplace violence on mental health nurses: a cross-sectional survey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Sun T, Gao L, Li F, Shi Y, Xie F, Wang J, et al. Workplace violence, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health in Chinese doctors: a large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017182. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Wu S, Lin S, Li H, Chai W, Zhang Q, Wu Y, et al. A study on workplace violence and its effect on quality of life among medical professionals in China. Arch Environ Occup Heal. 2014;69(2):81–88. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2012.732124. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Isaksson U, Graneheim UH, Richter J, Eisemann M, Åström S. Exposure to violence in relation to personality traits, coping abilities, and burnout among caregivers in nursing homes: a case-control study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(4):551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00570.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Lin WQ, Wu J, Yuan LX, Zhang SC, Jing MJ, Zhang HS, et al. Workplace violence and job performance among community healthcare workers in China: the mediator role of quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(11):14872–14886. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114872. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. ILO, ICN, WHO, PSI. Workplace violence in the health sector country case studies research ınstruments survey questionnaire English, Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in The Health Sector. 2002. 1–14 p.

- 10. Van Weel C, Kidd MR. Why strengthening primary health care is essential to achieving universal health coverage. CMAJ. 2018;190(15):E463–E466. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170784. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Pompeii L, Benavides E, Pop O, Rojas Y, Emery R, Delclos G, et al. Workplace violence in outpatient physician clinics: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186587. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Sturbelle ICS, Dal Pai D, Tavares JP, de Lima TL, Riquinho DL, Ampos LF. Workplace violence in Family Health Units: a study of mixed methods. ACTA Paul Enferm. 2019;32(6):632–641. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Alsmael MM, Gorab AH, Alqahtani AM. Violence against healthcare workers at primary care centers in Dammam and al Khobar, eastern province, Saudi Arabia, 2019. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:667–676. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S267446. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Selman S, Siddique L. Role of primary care in health systems strengthening achievements, challenges, and suggestions. Open J Soc Sci. 2022;10(10):359–367. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dussault G, Kawar R, Lopes SC, Campbell J. Building the primary health care workforce of the 21st century. World Heal Organ. 2019;29. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328072

- 16. WHO. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Who. 2016;64. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/global_strategy_workforce2030_14_print.pdf?ua=1

- 17. Labonté R, Sanders D, Packer C, Schaay N. Is the Alma Ata vision of comprehensive primary health care viable? Findings from an international project. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):24997. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24997. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Abed M, Morris E, Sobers-Grannum N. Workplace violence against medical staff in healthcare facilities in Barbados. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2016;66(7):580–583. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqw073. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Demeur V, Devos S, Jans E, Schoenmakers B. Aggression towards the GP: can we profile the GP-victim? A cross-section survey among GPs. BJGP Open. 2018;2(3):1–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen18X101604. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Elston MA, Gabe J. Violence in general practice: a gendered risk? Sociol Heal Illn. 2016;38(3):426–441. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12373. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Gan Y, Li L, Jiang H, Lu K, Yan S, Cao S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with workplace violence against general practitioners in Hubei, China. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1223–1226. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304519. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Joa TS, Morken T. Violence towards personnel in out-of-hours primary care: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30(1):55–60. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2012.651570. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Ko M, Dorri A. Primary care clinician and clinic director experiences of professional bias, harassment, and discrimination in an underserved agricultural region of California. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):1–20. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13535. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Pina D, López-Ros P, Luna-Maldonado A, Luna Ruiz-Caballero A, Llor-Esteban B, Ruiz-Hernández JA, et al. Users’ perception of violence and conflicts with professionals in primary care centers before and during COVID-19. A qualitative study. Front Public Heal. 2021;9(December):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.810014. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Pina D, Peñalver-Monteagudo CM, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Rabadán-García JA, López-Ros P, Martínez-Jarreta B. Sources of conflict and prevention proposals in user violence toward primary care staff: a qualitative study of the perception of professionals. Front Public Heal. 2022;10(June):1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.862896. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Sturbelle ICS, Pai DD, Tavares JP, de Trindade LL, Beck CLC, de Matos VZ. Workplace violence types in family health, offenders, reactions, and problems experienced. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(1):e20190055. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0055. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Vorderwülbecke F, Feistle M, Mehring M, Schneider A, Linde K. Aggression and violence against primary care physicians - A nationwide questionnaire survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(10):159–165. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0159. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Rajakrishnan S, Abdullah VHCW, Aghamohammadi N. Organizational safety climate and workplace violence among primary healthcare workers in Malaysia. Int J Public Heal Sci. 2022;11(1):88. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Al-Turki N, Afify AAM, Alateeq M. Violence against health workers in family medicine centers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:257–266. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S105407. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Irwin A, Laing C, Mearns K. The impact of patient aggression on community pharmacists: a critical incident study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(1):20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00222.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Jatic Z, Erkocevic H, Trifunovic N, Tatarevic E, Keco A, Sporisevic L, et al. Frequency and forms of workplace violence in primary health care. Med Arch (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina) 2019;73(1):6–10. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2019.73.6-10. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Miedema B, Macintyre L, Tatemichi S, Lambert-Lanning A, Lemire F, Manca D, et al. How the medical culture contributes to coworker-perpetrated harassment and abuse of family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):111–117. doi: 10.1370/afm.1341. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Rincón-Del Toro T, Villanueva-Guerra A, Rodríguez-Barrientos R, Polentinos-Castro E, Torijano-Castillo MJ, de Castro-Monteiro E, et al. Aggressions towards primary health care workers in Madrid, Spain, 2011–2012. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2016;90:e1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. López-García C, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Llor-Zaragoza L, Llor-Zaragoza P, Jiménez-Barbero JA. User violence and psychological well-being in primary health-care professionals. Eur J Psychol Appl to Leg Context. 2018;10(2):57–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Fisekovic Kremic MB, Terzic-Supic ZJ, Santric-Milicevic MM, Trajkovic GZ. Encouraging employees to report verbal violence in primary health care in Serbia: a cross-sectional study. Zdr Varst. 2017;56(1):11–17. doi: 10.1515/sjph-2017-0002. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Fisekovic MB, Trajkovic GZ, Bjegovic-Mikanovic VM, Terzic-Supic ZJ. Does workplace violence exist in primary health care? Evidence from Serbia. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(4):693–698. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku247. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Pina D, Llor-Zaragoza P, López-López R, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Puente-López E, Galián-Munoz I, et al. Assessment of non-physical user violence and burnout in primary health care professionals. The modulating role of job satisfaction. Front Public Heal. 2022;10(February):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.777412. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Feng J, Lei Z, Yan S, Jiang H, Shen X, Zheng Y, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for workplace violence among general practitioners in China: a national cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00736-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Delak B, Širok K. Physician–nurse conflict resolution styles in primary health care. Nurs Open. 2022;9(2):1077–1085. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1147. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Mento C, Silvestri MC, Bruno A, Muscatello MRA, Cedro C, Pandolfo G, et al. Workplace violence against healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2020;51:101381. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101381. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Ramzi ZS, Fatah PW, Dalvandi A. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13(May):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.896156. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. LanctÔt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(5):492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.010. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Nyberg A, Kecklund G, Hanson LM, Rajaleid K. Workplace violence and health in human service industries: a systematic review of prospective and longitudinal studies. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(2):69–81. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106450. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Wassell JT. Workplace violence intervention effectiveness: a systematic literature review. Saf Sci. 2009;47(8):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2008.12.001. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Edward K, Stephenson J, Ousey K, Lui S, Warelow P, Giandinoto JA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(3–4):289–299. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Chakraborty S, Mashreky SR, Dalal K. Violence against physicians and nurses: a systematic literature review. J Public Heal. 2022;30(8):1837–1855. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-01689-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Njaka S, Edeogu OC, Oko CC, Goni MD, Nkadi N. Work place violence (WPV) against healthcare workers in Africa: a systematic review. Heliyon. 2020;6(9):e04800. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04800. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Hall BJ, Xiong P, Chang K, Yin M, Sui XR. Prevalence of medical workplace violence and the shortage of secondary and tertiary interventions among healthcare workers in China. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(6):516–518. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208602. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Li YL, Li RQ, Qiu D, Xiao SY. Prevalence of workplace physical violence against health care professionals by patients and visitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(1):299. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010299. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Nelson R. Tackling violence against health-care workers. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1373–1374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60658-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. IAHSSF Crime and Incident Survey – 2017 | IAHSSF: International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety Foundation - Education and Professional Advancement. 2020. https://iahssf.org/crime-surveys/iahssf-crime-and-incident-survey-2017/ .

- 53. Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Miller M, Howard PK. Workplace violence in healthcare settings: risk factors and protective strategies (CE) Rehabil Nurs. 2010;35(5):177–184. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00045.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Albashtawy M. Workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;2013:550–555. doi: 10.1111/inr.12059. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Uzembo BAM, Butshu LHM, Gatu NRN, Alonga KFM, Itoku ME, Irota RH, et al. Workplace violence towards Congolese health care workers: a survey of 436 healthcare facilities in Katanga province, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Occup Health. 2015;57:69–80. doi: 10.1539/joh.14-0111-OA. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Taylor JL, Rew L. A systematic review of the literature : workplace violence in the emergency department. Clin Nurs. 2010;20:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03342.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. OSHA. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for health care and social service workers. Vol. 66, U.S. Department of Labor. Washington D.C; 2016. [ PubMed ]

- 58. Abdullah Aloraier H, Mousa Altamimi R, Ahmed Allami E, Abdullah Alqahtani R, Shabib Almutairi T, AlQuaiz AM, et al. Sexual harassment and mental health of female healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30860. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30860. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Gagnon DR, Doron-LaMarca S, Bell M, O’Farrell IJ, Casey T. Poisson regression for modeling count and frequency outcomes in trauma research. J Traum Stress. 2008;21(5):448–454. doi: 10.1002/jts.20359. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernández-Sánchez J, Solli P. Longitudinal studies. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(11):E537–E540. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Nowrouzi-Kia B, Chai E, Usuba K, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Casole J. Prevalence of type ii and type iii workplace violence against physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10(3):99–110. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2019.1573. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Hershcovis MS, Barling J. Comparing victim attributions and outcomes for workplace aggression and sexual harassment. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(5):874–888. doi: 10.1037/a0020070. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Staggs VS. Injurious assault rates on inpatient psychiatric units: associations with staffing by registered nurses and other nursing personnel. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1162–1166. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400453. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Kalra G, Bhugra D. Sexual violence against women: understanding cross-cultural intersections. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(3):244–249. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.117139. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Awadalla, Crystal A; Roughton JE. Workplace Violence Prevention: The New Safety Focus [Internet]. Vol. 43, Professional Safety. 1998. p. 31–5. Available from: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/ehost/delivery?sid=4084d506-05ce-4fb1-8908-931f978a4b9a%40sessionmgr102&vid=3&hid=118&ReturnUrl =…

- 66. Ferris RW, Murphy D. Workplace Safety: Establishing an Effective Violence Prevention Program. Workplace Safety: Establishing an Effective Violence Prevention Program. 2015. p. 1–159.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.1 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This paper addresses the problem of workplace violence. Because research into workplace violence is relatively new, there is not much research into managerial response to violent incidences. This paper helps to establish a template that may become a useful managerial tool to decrease the potential for future workplace violence that may lead to

In this paper, the concept of workplace violence is defined and several examples are given for reference. The paper will discuss the responsibility of the Human Resources Management team to identify a potential problem before violence occurs, and also prevent work place violence through adequate and necessary training of employees.

warrant their separate categorization. For example, in their systematic review, Piquero et al. (2013) adopted a narrow definition of workplace violence viewing it as a distinct form of workplace aggression, specifically referring to behaviors intended to cause physical harm, to synthesize previous research findings.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare workers, exposing them to unprecedented levels of aggression. Incidents of verbal abuse, threats, and physical assaults have increased, especially in high-stress environments such as emergency departments and intensive care units, exacerbating psychological ...

Workplace violence prevention team- this team is made up of a group of employees and serves as a sub committee in the prevention of workplace violence. This team is composed of the director of safety and security, human resources manager and other senior staff.

bulk of research about healthcare WPV focuses on interventions and strategies to prevent violence from occurring. While prevention is important, researchers must also examine how HCW process the aftereffects of violence at work. Workplace violence often elicits unfavorable consequences for workers, including HCW.

PRISMA flow diagram. Results General characteristics of the studies. Forty-three articles were potentially eligible for further consideration, but only 23 articles provided information that answered the research questions (Table 1) [13, 19-40].The studies mainly covered 16 countries across Asia, Europe, and North and South America, thus providing good ethnic or cultural background diversity.