- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

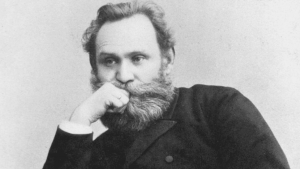

Pavlov's Dogs and the Discovery of Classical Conditioning

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

Jules Clark/Getty Images

- Pavlov's Theory

Pavlov's dog experiments played a critical role in the discovery of one of the most important concepts in psychology: Classical conditioning .

While it happened quite by accident, Pavlov's famous experiments had a major impact on our understanding of how learning takes place as well as the development of the school of behavioral psychology. Classical conditioning is sometimes called Pavlovian conditioning.

Pavlov's Dog: A Background

How did experiments on the digestive response in dogs lead to one of the most important discoveries in psychology? Ivan Pavlov was a noted Russian physiologist who won the 1904 Nobel Prize for his work studying digestive processes.

While studying digestion in dogs, Pavlov noted an interesting occurrence: His canine subjects would begin to salivate whenever an assistant entered the room.

The concept of classical conditioning is studied by every entry-level psychology student, so it may be surprising to learn that the man who first noted this phenomenon was not a psychologist at all.

In his digestive research, Pavlov and his assistants would introduce a variety of edible and non-edible items and measure the saliva production that the items produced.

Salivation, he noted, is a reflexive process. It occurs automatically in response to a specific stimulus and is not under conscious control.

However, Pavlov noted that the dogs would often begin salivating in the absence of food and smell. He quickly realized that this salivary response was not due to an automatic, physiological process.

Pavlov's Theory of Classical Conditioning

Based on his observations, Pavlov suggested that the salivation was a learned response. Pavlov's dog subjects were responding to the sight of the research assistants' white lab coats, which the animals had come to associate with the presentation of food.

Unlike the salivary response to the presentation of food, which is an unconditioned reflex, salivating to the expectation of food is a conditioned reflex.

Pavlov then focused on investigating exactly how these conditioned responses are learned or acquired. In a series of experiments, he set out to provoke a conditioned response to a previously neutral stimulus.

He opted to use food as the unconditioned stimulus , or the stimulus that evokes a response naturally and automatically. The sound of a metronome was chosen to be the neutral stimulus.

The dogs would first be exposed to the sound of the ticking metronome, and then the food was immediately presented.

After several conditioning trials, Pavlov noted that the dogs began to salivate after hearing the metronome. "A stimulus which was neutral in and of itself had been superimposed upon the action of the inborn alimentary reflex," Pavlov wrote of the results.

"We observed that, after several repetitions of the combined stimulation, the sounds of the metronome had acquired the property of stimulating salivary secretion."

In other words, the previously neutral stimulus (the metronome) had become what is known as a conditioned stimulus that then provoked a conditioned response (salivation).

To review, the following are some key components used in Pavlov's theory:

- Conditioned stimulus : This is what the neutral stimulus becomes after training (i.e., the metronome was the conditioned stimulus after Pavlov trained the dogs to respond to it)

- Unconditioned stimulus : A stimulus that produces an automatic response (i.e., the food was the unconditioned stimulus because it made the dogs automatically salivate)

- Conditioned response (conditioned reflex) : A learned response to previously neutral stimulus (i.e., the salivation was a conditioned response to the metronome)

- Unconditioned response (unconditioned reflex) : A response that is automatic (i.e., the dog's salivating is an unconditioned response to the food)

Impact of Pavlov's Research

Pavlov's discovery of classical conditioning remains one of the most important in psychology's history.

In addition to forming the basis of what would become behavioral psychology , the classical conditioning process remains important today for numerous applications, including behavioral modification and mental health treatment.

Principles of classical conditioning are used to treat the following mental health disorders:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Panic attacks and panic disorder

- Substance use disorders

For instance, a specific type of treatment called aversion therapy uses conditioned responses to help people with anxiety or a specific phobia.

A therapist will help a person face the object of their fear gradually—while helping them manage any fear responses that arise. Gradually, the person will form a neutral response to the object.

Pavlov’s work has also inspired research on how to apply classical conditioning principles to taste aversions . The principles have been used to prevent coyotes from preying on domestic livestock and to use neutral stimulus (eating some type of food) paired with an unconditioned response (negative results after eating the food) to create an aversion to a particular food.

Unlike other forms of classical conditioning, this type of conditioning does not require multiple pairings in order for an association to form. In fact, taste aversions generally occur after just a single pairing. Ranchers have found ways to put this form of classical conditioning to good use to protect their herds.

In one example, mutton was injected with a drug that produces severe nausea. After eating the poisoned meat, coyotes then avoided sheep herds rather than attack them.

A Word From Verywell

While Pavlov's discovery of classical conditioning formed an essential part of psychology's history, his work continues to inspire further research today. His contributions to psychology have helped make the discipline what it is today and will likely continue to shape our understanding of human behavior for years to come.

Adams M. The kingdom of dogs: Understanding Pavlov’s experiments as human–animal relationships . Theory & Psychology . 2019;30(1):121-141. doi:10.1177/0959354319895597

Fanselow MS, Wassum KM. The origins and organization of vertebrate Pavlovian conditioning . Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;8(1):a021717. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021717

Nees F, Heinrich A, Flor H. A mechanism-oriented approach to psychopathology: The role of Pavlovian conditioning . Int J Psychophysiol. 2015;98(2):351-364. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.05.005

American Psychological Association. What is exposure therapy?

Lin JY, Arthurs J, Reilly S. Conditioned taste aversions: From poisons to pain to drugs of abuse. Psychon Bull Rev . 2017;24(2):335-351. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1092-8

Gustafson, C.R., Kelly, D.J, Sweeney, M., & Garcia, J. Prey-lithium aversions: I. Coyotes and wolves. Behavioral Biology. 1976; 17: 61-72.

Hock, R.R. Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research. (4th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2002.

- Gustafson, C.R., Garcia, J., Hawkins, W., & Rusiniak, K. Coyote predation control by aversive conditioning. Science. 1974; 184: 581-583.

- Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned reflexes . London: Oxford University Press; 1927.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Classical conditioning (also known as Pavlovian or respondent conditioning) is learning through association and was discovered by Pavlov , a Russian physiologist. In simple terms, two stimuli are linked together to produce a new learned response in a person or animal.

John B. Watson proposed that the process of classical conditioning (based on Pavlov’s observations) was able to explain all aspects of human psychology.

If you pair a neutral stimulus (NS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US) that already triggers an unconditioned response (UR) that neutral stimulus will become a conditioned stimulus (CS), triggering a conditioned response (CR) similar to the original unconditioned response.

Everything from speech to emotional responses was simply patterns of stimulus and response. Watson completely denied the existence of the mind or consciousness. Watson believed that all individual differences in behavior were due to different learning experiences.

Watson (1924, p. 104) famously said:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select – doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations and the race of his ancestors.

How Classical Conditioning Works

There are three stages of classical conditioning. At each stage, the stimuli and responses are given special scientific terms:

Stage 1: Before Conditioning:

In this stage, the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) produces an unconditioned response (UCR) in an organism.

In basic terms, this means that a stimulus in the environment has produced a behavior/response that is unlearned (i.e., unconditioned) and, therefore, is a natural response that has not been taught. In this respect, no new behavior has been learned yet.

For example, a stomach virus (UCS) would produce a response of nausea (UCR). In another example, a perfume (UCS) could create a response of happiness or desire (UCR).

This stage also involves another stimulus that has no effect on a person and is called the neutral stimulus (NS). The NS could be a person, object, place, etc.

The neutral stimulus in classical conditioning does not produce a response until it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

Stage 2: During Conditioning:

During this stage, a stimulus which produces no response (i.e., neutral) is associated with the unconditioned stimulus, at which point it now becomes known as the conditioned stimulus (CS).

For example, a stomach virus (UCS) might be associated with eating a certain food such as chocolate (CS). Also, perfume (UCS) might be associated with a specific person (CS).

For classical conditioning to be effective, the conditioned stimulus should occur before the unconditioned stimulus, rather than after it, or during the same time. Thus, the conditioned stimulus acts as a type of signal or cue for the unconditioned stimulus.

In some cases, conditioning may take place if the NS occurs after the UCS (backward conditioning), but this normally disappears quite quickly. The most important aspect of the conditioning stimulus is the it helps the organism predict the coming of the unconditional stimulus.

Often during this stage, the UCS must be associated with the CS on a number of occasions, or trials, for learning to take place.

However, one trial learning can happen on certain occasions when it is not necessary for an association to be strengthened over time (such as being sick after food poisoning or drinking too much alcohol).

Stage 3: After Conditioning:

The conditioned stimulus (CS) has been associated with the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) to create a new conditioned response (CR).

For example, a person (CS) who has been associated with nice perfume (UCS) is now found attractive (CR). Also, chocolate (CS) which was eaten before a person was sick with a virus (UCS) now produces a response of nausea (CR).

Classical Conditioning Examples

Pavlov’s dogs.

The most famous example of classical conditioning was Ivan Pavlov’s experiment with dogs , who salivated in response to a bell tone. Pavlov showed that when a bell was sounded each time the dog was fed, the dog learned to associate the sound with the presentation of the food.

He first presented the dogs with the sound of a bell; they did not salivate so this was a neutral stimulus. Then he presented them with food, they salivated. The food was an unconditioned stimulus, and salivation was an unconditioned (innate) response.

He then repeatedly presented the dogs with the sound of the bell first and then the food (pairing) after a few repetitions, the dogs salivated when they heard the sound of the bell. The bell had become the conditioned stimulus and salivation had become the conditioned response.

Fear Response

Watson & Rayner (1920) were the first psychologists to apply the principles of classical conditioning to human behavior by looking at how this learning process may explain the development of phobias.

They did this in what is now considered to be one of the most ethically dubious experiments ever conducted – the case of Little Albert . Albert B.’s mother was a wet nurse in a children’s hospital. Albert was described as ‘healthy from birth’ and ‘on the whole stolid and unemotional’.

When he was about nine months old, his reactions to various stimuli (including a white rat, burning newspapers, and a hammer striking a four-foot steel bar just behind his head) were tested.

Only the last of these frightened him, so this was designated the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and fear the unconditioned response (UCR). The other stimuli were neutral because they did not produce fear.

When Albert was just over eleven months old, the rat and the UCS were presented together: as Albert reached out to stroke the animal, Watson struck the bar behind his head.

This occurred seven times in total over the next seven weeks. By this time, the rat, the conditioned stimulus (CS), on its own frightened Albert, and fear was now a conditioned response (CR).

The CR transferred spontaneously to the rabbit, the dog, and other stimuli that had been previously neutral. Five days after conditioning, the CR produced by the rat persisted. After ten days, it was ‘much less marked’, but it was still evident a month later.

Carter and Tiffany (1999) support the cue reactivity theory, they carried out a meta-analysis reviewing 41 cue-reactivity studies that compared responses of alcoholics, cigarette smokers, cocaine addicts and heroin addicts to drug-related versus neutral stimuli.

They found that dependent individuals reacted strongly to the cues presented and reported craving and physiological arousal.

Panic Disorder

Classical conditioning is thought to play an important role in the development of Pavlov (Bouton et al., 2002).

Panic disorder often begins after an initial “conditioning episode” involving an early panic attack. The panic attack serves as an unconditioned stimulus (US) that gets paired with neutral stimuli (conditioned stimuli or CS), allowing those stimuli to later trigger anxiety and panic reactions (conditioned responses or CRs).

The panic attack US can become associated with interoceptive cues (like increased heart rate) as well as external situational cues that are present during the attack. This allows those cues to later elicit anxiety and possibly panic (CRs).

Through this conditioning process, anxiety becomes focused on the possibility of having another panic attack. This anticipatory anxiety (a CR) is seen as a key step in the development of panic disorder, as it leads to heightened vigilance and sensitivity to bodily cues that can trigger future attacks.

The presence of conditioned anxiety can serve to potentiate or exacerbate future panic attacks. Anxiety cues essentially lower the threshold for panic. This helps explain how panic disorder can spiral after the initial conditioning episode.

Evidence suggests most patients with panic disorder recall an initial panic attack or conditioning event that preceded the disorder. Prospective studies also show conditioned anxiety and panic reactions can develop after an initial panic episode.

Classical conditioning processes are believed to often occur outside of conscious awareness in panic disorder, reflecting the operation of emotional neural systems separate from declarative knowledge systems.

Cue reactivity is the theory that people associate situations (e.g., meeting with friends)/ places (e.g., pub) with the rewarding effects of nicotine, and these cues can trigger a feeling of craving (Carter & Tiffany, 1999).

These factors become smoking-related cues. Prolonged use of nicotine creates an association between these factors and smoking based on classical conditioning.

Nicotine is the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), and the pleasure caused by the sudden increase in dopamine levels is the unconditioned response (UCR). Following this increase, the brain tries to lower the dopamine back to a normal level.

The stimuli that have become associated with nicotine were neutral stimuli (NS) before “learning” took place but they became conditioned stimuli (CS), with repeated pairings. They can produce the conditioned response (CR).

However, if the brain has not received nicotine, the levels of dopamine drop, and the individual experiences withdrawal symptoms therefore is more likely to feel the need to smoke in the presence of the cues that have become associated with the use of nicotine.

Classroom Learning

The implications of classical conditioning in the classroom are less important than those of operant conditioning , but there is still a need for teachers to try to make sure that students associate positive emotional experiences with learning.

If a student associates negative emotional experiences with school, then this can obviously have bad results, such as creating a school phobia.

For example, if a student is bullied at school they may learn to associate the school with fear. It could also explain why some students show a particular dislike of certain subjects that continue throughout their academic career. This could happen if a student is humiliated or punished in class by a teacher.

Principles of Classical Conditioning

Neutral stimulus.

In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus (NS) is a stimulus that initially does not evoke a response until it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, in Pavlov’s experiment, the bell was the neutral stimulus, and only produced a response when paired with food.

Unconditioned Stimulus

Unconditioned response.

In classical conditioning, an unconditioned response is an innate response that occurs automatically when the unconditioned stimulus is presented.

Pavlov showed the existence of the unconditioned response by presenting a dog with a bowl of food and measuring its salivary secretions.

Conditioned Stimulus

Conditioned response.

In classical conditioning, the conditioned response (CR) is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus.

In Ivan Pavlov’s experiments in classical conditioning, the dog’s salivation was the conditioned response to the sound of a bell.

Acquisition

The process of pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to produce a conditioned response.

In the initial learning period, acquisition describes when an organism learns to connect a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus.

In psychology, extinction refers to the gradual weakening of a conditioned response by breaking the association between the conditioned and the unconditioned stimuli.

The weakening of a conditioned response occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, when the bell repeatedly rang, and no food was presented, Pavlov’s dog gradually stopped salivating at the sound of the bell.

Spontaneous Recovery

Spontaneous recovery is a phenomenon of Pavlovian conditioning that refers to the return of a conditioned response (in a weaker form) after a period of time following extinction.

It is the reappearance of an extinguished conditioned response after a rest period when the conditioned stimulus is presented alone.

For example, when Pavlov waited a few days after extinguishing the conditioned response, and then rang the bell once more, the dog salivated again.

Generalization

In psychology, generalization is the tendency to respond in the same way to stimuli similar (but not identical) to the original conditioned stimulus.

For example, in Pavlov’s experiment, if a dog is conditioned to salivate to the sound of a bell, it may later salivate to a higher-pitched bell.

Discrimination

In classical conditioning, discrimination is a process through which individuals learn to differentiate among similar stimuli and respond appropriately to each one.

For example, eventually, Pavlov’s dog learns the difference between the sound of the 2 bells and no longer salivates at the sound of the non-food bell.

Higher-Order Conditioning

Higher-order conditioning is when a conditioned stimulus is paired with a new neutral stimulus to create a second conditioned stimulus. For example, a bell (CS1) is paired with food (UCS) so that the bell elicits salivation (CR). Then, a light (NS) is paired with the bell.

Eventually, the light alone will elicit salivation, even without the presence of food. This demonstrates higher-order conditioning, where the conditioned stimulus (bell) serves as an unconditioned stimulus to condition a new stimulus (light).

Critical Evaluation

Practical applications.

The principles of classical conditioning have been widely and effectively applied in fields like behavioral therapy, education, and advertising. Therapies like systematic desensitization use classical conditioning to help eliminate phobias and anxiety.

The behaviorist approach has been used in the treatment of phobias, and systematic desensitization . The individual with the phobia is taught relaxation techniques and then makes a hierarchy of fear from the least frightening to the most frightening features of the phobic object.

He then is presented with the stimuli in that order and learns to associate (classical conditioning) the stimuli with a relaxation response. This is counter-conditioning.

Explaining involuntary behaviors

Classical conditioning helps explain some reflexive or involuntary behaviors like phobias, emotional reactions, and physiological responses. The model shows how these can be acquired through experience.

The process of classical conditioning can probably account for aspects of certain other mental disorders. For example, in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sufferers tend to show classically conditioned responses to stimuli present at the time of the traumatizing event (Charney et al., 1993).

However, since not everyone exposed to the traumatic event develops PTSD, other factors must be involved, such as individual differences in people’s appraisal of events as stressors and the recovery environment, such as family and support groups.

Supported by substantial experimental evidence

There is a wealth of experimental support for basic phenomena like acquisition, extinction, generalization, and discrimination. Pavlov’s original experiments on dogs and subsequent studies have demonstrated classical conditioning in animals and humans.

There have been many laboratory demonstrations of human participants acquiring behavior through classical conditioning. It is relatively easy to classically condition and extinguish conditioned responses, such as the eye-blink and galvanic skin responses.

A strength of classical conditioning theory is that it is scientific . This is because it’s based on empirical evidence carried out by controlled experiments . For example, Pavlov (1902) showed how classical conditioning could be used to make a dog salivate to the sound of a bell.

Supporters of a reductionist approach say that it is scientific. Breaking complicated behaviors down into small parts means that they can be scientifically tested. However, some would argue that the reductionist view lacks validity . Thus, while reductionism is useful, it can lead to incomplete explanations.

Ignores biological predispositions

Organisms are biologically prepared to associate certain stimuli over others. However, classical conditioning does not sufficiently account for innate predispositions and biases.

Classical conditioning emphasizes the importance of learning from the environment, and supports nurture over nature.

However, it is limiting to describe behavior solely in terms of either nature or nurture , and attempts to do this underestimate the complexity of human behavior. It is more likely that behavior is due to an interaction between nature (biology) and nurture (environment).

Lacks explanatory power

Classical conditioning provides limited insight into the cognitive processes underlying the associations it describes.

However, applying classical conditioning to our understanding of higher mental functions, such as memory, thinking, reasoning, or problem-solving, has proved more problematic.

Even behavior therapy, one of the more successful applications of conditioning principles to human behavior, has given way to cognitive–behavior therapy (Mackintosh, 1995).

Questionable ecological validity

While lab studies support classical conditioning, some question how well it holds up in natural settings. There is debate about how automatic and inevitable classical conditioning is outside the lab.

In normal adults, the conditioning process can be overridden by instructions: simply telling participants that the unconditioned stimulus will not occur causes an instant loss of the conditioned response, which would otherwise extinguish only slowly (Davey, 1983).

Most participants in an experiment are aware of the experimenter’s contingencies (the relationship between stimuli and responses) and, in the absence of such awareness often fail to show evidence of conditioning (Brewer, 1974).

Evidence indicates that for humans to exhibit classical conditioning, they need to be consciously aware of the connection between the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the unconditioned stimulus (US). This contradicts traditional theories that humans have two separate learning systems – one conscious and one unconscious – that allow conditioning to occur without conscious awareness (Lovibond & Shanks, 2002).

There are also important differences between very young children or those with severe learning difficulties and older children and adults regarding their behavior in a variety of operant conditioning and discrimination learning experiments.

These seem largely attributable to language development (Dugdale & Lowe, 1990). This suggests that people have rather more efficient, language-based forms of learning at their disposal than just the laborious formation of associations between a conditioned stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus.

Ethical concerns

The principles of classical conditioning raise ethical concerns about manipulating behavior without consent. This is especially true in advertising and politics.

- Manipulation of preferences – Classical conditioning can create positive associations with certain brands, products, or political candidates. This can manipulate preferences outside of a person’s rational thought process.

- Encouraging impulsive behaviors – Conditioning techniques may encourage behaviors like impulsive shopping, unhealthy eating, or risky financial choices by forging positive associations with these behaviors.

- Preying on vulnerabilities – Advertisers or political campaigns may exploit conditioning techniques to target and influence vulnerable demographic groups like youth, seniors, or those with mental health conditions.

- Reduction of human agency – At an extreme, the use of classical conditioning techniques reduces human beings to automata reacting predictably to stimuli. This is ethically problematic.

Deterministic theory

A final criticism of classical conditioning theory is that it is deterministic . This means it does not allow the individual any degree of free will. Accordingly, a person has no control over the reactions they have learned from classical conditioning, such as a phobia.

The deterministic approach also has important implications for psychology as a science. Scientists are interested in discovering laws that can be used to predict events.

However, by creating general laws of behavior, deterministic psychology underestimates the uniqueness of human beings and their freedom to choose their destiny.

The Role of Nature in Classical Conditioning

Behaviorists argue all learning is driven by experience, not nature. Classical conditioning exemplifies environmental influence. However, our evolutionary history predisposes us to learn some associations more readily than others. So nature also plays a role.

For example, PTSD develops in part due to strong conditioning during traumatic events. The emotions experienced during trauma lead to neural activity in the amygdala , creating strong associative learning between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli (Milad et al., 2009).

Individuals with PTSD show enhanced fear conditioning, reflected in greater amygdala reactivity to conditioned threat cues compared to trauma-exposed controls. In addition to strong initial conditioning, PTSD patients exhibit slower extinction to conditioned fear stimuli.

During extinction recall tests, PTSD patients fail to show differential skin conductance responses to extinguished versus non-extinguished cues, indicating impaired retention of fear extinction. Deficient extinction retention corresponds to reduced activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and heightened dorsal anterior cingulate cortex response during extinction recall in PTSD patients.

In influential research on food conditioning, John Garcia found that rats easily learned to associate a taste with nausea from drugs, even if illness occurred hours later.

However, conditioning nausea to a sight or sound was much harder. This showed that conditioning does not occur equally for any stimulus pairing. Rather, evolution prepares organisms to learn some associations that aid survival more easily, like linking smells to illness.

The evolutionary significance of taste and nutrition ensures robust and resilient classical conditioning of flavor preferences, making them difficult to reverse (Hall, 2002).

Forming strong and lasting associations between flavors and nutrition aids survival by promoting the consumption of calorie-rich foods. This makes flavor conditioning very robust.

Repeated flavor-nutrition pairings in these studies lead to overlearning of the association, making it more resistant to extinction.

The learning is overtrained, context-specific, and subject to recovery effects that maintain the conditioned behavior despite extinction training.

Classical vs. operant condioning

In summary, classical conditioning is about passive stimulus-response associations, while operant conditioning is about actively connecting behaviors to consequences. Classical works on reflexes and operant on voluntary actions.

- Stimuli vs consequences : Classical conditioning focuses on associating two stimuli together. For example, pairing a bell (neutral stimulus) with food (reflex-eliciting stimulus) creates a conditioned response of salivation to the bell. Operant conditioning is about connecting behaviors with the consequences that follow. If a behavior is reinforced, it will increase. If it’s punished, it will decrease.

- Passive vs. active : In classical conditioning, the organism is passive and automatically responds to the conditioned stimulus. Operant conditioning requires the organism to perform a behavior that then gets reinforced or punished actively. The organism operates on the environment.

- Involuntary vs. voluntary : Classical conditioning works with involuntary, reflexive responses like salivation, blinking, etc. Operant conditioning shapes voluntary behaviors that are controlled by the organism, like pressing a lever.

- Association vs. reinforcement : Classical conditioning relies on associating stimuli in order to create a conditioned response. Operant conditioning depends on using reinforcement and punishment to increase or decrease voluntary behaviors.

Learning Check

- In Ivan Pavlov’s famous experiment, he rang a bell before presenting food powder to dogs. Eventually, the dogs salivated at the mere sound of the bell. Identify the neutral stimulus, unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response in Pavlov’s experiment.

- A student loves going out for pizza and beer with friends on Fridays after class. Whenever one friend texts the group about Friday plans, the student immediately feels happy and excited. The friend starts texting the group on Thursdays when she wants the student to feel happier. Explain how this is an example of classical conditioning. Identify the UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

- A college student is traumatized after a car accident. She now feels fear every time she gets into a car. How could extinction be used to eliminate this acquired fear?

- A professor always slams their book on the lectern right before giving a pop quiz. Students now feel anxiety whenever they hear the book slam. Is this classical conditioning? If so, identify the NS, UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

- Contrast classical conditioning and operant conditioning. How are they similar and different? Provide an original example of each type of conditioning.

- How could the principles of classical conditioning be applied to help students overcome test anxiety?

- Explain how taste aversion learning is an adaptive form of classical conditioning. Provide an original example.

- What is second-order conditioning? Give an example and identify the stimuli and responses.

- What is the role of extinction in classical conditioning? How could extinction be used in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders?

Bouton, M. E., Mineka, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2001). A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder . Psychological Review , 108 (1), 4.

Bremner, J. D., Southwick, S. M., Johnson, D. R., Yehuda, R., & Charney, D. S. (1993). Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. The American journal of psychiatry .

Brewer, W. F. (1974). There is no convincing evidence for operant or classical conditioning in adult humans.

Carter, B. L., & Tiffany, S. T. (1999). Meta‐analysis of cue‐reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94 (3), 327-340.

Davey, B. (1983). Think aloud: Modeling the cognitive processes of reading comprehension. Journal of Reading, 27 (1), 44-47.

Dugdale, N., & Lowe, C. F. (1990). Naming and stimulus equivalence.

Garcia, J., Ervin, F. R., & Koelling, R. A. (1966). Learning with prolonged delay of reinforcement. Psychonomic Science, 5 (3), 121–122.

Garcia, J., Kimeldorf, D. J., & Koelling, R. A. (1955). Conditioned aversion to saccharin resulting from exposure to gamma radiation. Science, 122 , 157–158.

Hall, G. (2022). Extinction of conditioned flavor preferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition .

Logan, C. A. (2002). When scientific knowledge becomes scientific discovery: The disappearance of classical conditioning before Pavlov . Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences , 38 (4), 393-403.

Lovibond, P. F., & Shanks, D. R. (2002). The role of awareness in Pavlovian conditioning: empirical evidence and theoretical implications. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes , 28 (1), 3.

Milad, M. R., Pitman, R. K., Ellis, C. B., Gold, A. L., Shin, L. M., Lasko, N. B.,…Rauch, S. L. (2009). Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 66 (12), 1075–82.

Pavlov, I. P. (1897/1902). The work of the digestive glands . London: Griffin.

Thanellou, A., & Green, J. T. (2011). Spontaneous recovery but not reinstatement of the extinguished conditioned eyeblink response in the rat. Behavioral Neuroscience , 125 (4), 613.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it . Psychological Review, 20 , 158–177.

Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review, 20 , 158-177.

Watson, J. B. (1924). Behaviorism . New York: People’s Institute Publishing Company.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions . Journal of experimental psychology, 3 (1), 1.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Classical conditioning.

Ibraheem Rehman ; Navid Mahabadi ; Terrence Sanvictores ; Chaudhry I. Rehman .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 5, 2024 .

- Introduction

Learning is the process through which individuals acquire new knowledge, behaviors, attitudes, and ideas. Humans must be sensitive to both meaningful and coincidental relationships between events in the environment to survive. [1] This learning process happens through both unconscious and conscious pathways. Classical conditioning, also known as associative learning, is an unconscious process where an automatic, conditioned response becomes associated with a specific stimulus. Although Edwin Twitmyer published findings on classical conditioning a year before Ivan Pavlov, the most recognized work in the field is attributed to Pavlov (a Russian physiologist born in the mid-1800s). Pavlov's significant contributions to classical conditioning have led to the term "Pavlovian conditioning" being used to describe it. [2] [3]

The discovery of classical conditioning was accidental. While researching the digestion of dogs, Pavlov observed that the dogs' physical responses to food gradually changed. Initially, the dogs only salivated when the food was directly presented. However, he later noticed that the dogs began to salivate slightly before the food arrived in response to sounds consistently associated with feeding, such as the sound of the food cart. To test his theory, Pavlov conducted an experiment where he rang a bell shortly before presenting food to the dogs. Initially, the dogs did not salivate in response to the bell. However, as they learned to associate the sound of the bell with the arrival of food, they began to salivate at the sound alone. [4]

An unconditioned stimulus is something that naturally triggers an automatic response. In Pavlov's experiment, the food acted as the unconditioned stimulus. The unconditioned response is the automatic reaction to that stimulus, which in this case was the dogs salivating in response to the food.

A neutral stimulus initially elicits no response. Pavlov introduced the ringing of the bell as a neutral stimulus. Over time, a neutral stimulus can become a conditioned stimulus, which eventually triggers a conditioned response. In Pavlov's experiment, the ringing of the bell became the conditioned stimulus, and salivation was the conditioned response. Essentially, the neutral stimulus transforms into the conditioned stimulus. While the unconditioned and conditioned responses are the same physiological reaction—salivation—the difference lies in the stimulus that elicits them. In Pavlov's experiments, salivation was the response. The unconditioned response, triggered by food, was salivation, while the bell triggered the conditioned response.

Pavlov observed several phenomena related to classical conditioning. He found that the rate of acquisition during the initial stages of learning depended on the prominence of the stimulus and the timing between the introduction of the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, this was reflected in the interval between the bell ringing and the presentation of food. Pavlov also noted that the conditioned response was susceptible to extinction. If the conditioned stimulus was continuously supplied without the unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned response progressively weakened until it disappeared. For instance, if Pavlov rang the bell without presenting food, the dogs would eventually stop salivating in response to the bell. However, Pavlov also observed that spontaneous recovery could occur.

Even after a significant amount of time passed, the conditioned response would reappear if the neutral and unconditioned stimuli were paired again. Pavlov also discovered that stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination could occur. Stimulus generalization occurs when dogs respond to stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus. Conversely, stimulus discrimination is the ability to differentiate between similar stimuli and respond only to the specific, correct stimuli. [5] [6] [7]

- Issues of Concern

As seen in advertising, classical conditioning can influence people for gain. Advertisers try to create associations between their products and particular responses or feelings. Advertisers use music or mouth-watering food in their ads to establish a positive association with their product. These associations are highly effective in encouraging people to purchase the advertised product.

Applying aversive techniques is ethically questionable and a violation of an individual's civil rights. Punishment is a conditioning technique used by behavioral analysts, teachers, parents, and caregivers in schools, homes, and communities. Punishment contingencies are used disproportionately in preschool children and individuals with disabilities. Children with disabilities are 3.4 times more likely to experience maltreatment compared to those without disabilities. These individuals should be recognized as vulnerable and at greater risk of abuse. [8]

- Clinical Significance

The profound influence of Pavlovian conditioning principles on health, emotion, motivation, and mental health therapies is a fascinating area of study. For example, individuals with a history of substance use may experience cravings when they are in environments where they previously used substances or around people they associate with previous substance use. The behaviorally conditioned, or learned, immune response is another example of classical conditioning. When a specific taste is paired with a drug affecting the immune system, the taste alone can trigger the immune response later. [9]

Exposure therapy aims to treat anxiety disorders by gradually exposing patients to the source of their fear in a controlled and safe environment, often using images, simulations, or videos. A newer area of research focuses on virtual reality or augmented reality exposure therapy, where gradual exposure to negative stimuli is used to reduce anxiety. [10] [11]

Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is common, affecting approximately 5% to 7% of children aged 7. The current understanding is that enuresis is due to a mismatch between nocturnal urine production, bladder capacity, and the ability to wake up during sleep. The enuresis alarm is a device that provides a strong arousal stimulus, such as sound or vibration, to alert the child and family when urine activates a detector in the child's bed or clothing, helping the child wake up. The success rate ranges from 50% to 70%, and a significant proportion of those successfully treated achieve long-term resolution. [12]

- Other Issues

Depending on the diagnosis, combining psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can lead to better clinical outcomes than using either treatment alone. [13] [14] [15] The combined treatment for managing depression is more effective than either psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone, with no significant differences in efficacy between the 2 individual therapies. [16] Additionally, the use of antidepressants does not interfere with the effects of psychotherapy. [17]

For adult posttraumatic stress disorder, current evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that concurrent medication neither enhances nor diminishes the efficacy of psychological interventions. [18] Anxiety disorders should be treated with psychological therapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both. [19]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cohesiveness and consistency of the interprofessional healthcare team implementing classical conditioning interventions are crucial for success. [20] [21] A strategic, evidence-based approach is essential to optimize treatment plans and minimize adverse effects. Ethical considerations must guide decision-making, ensuring informed consent and respecting patient autonomy. Each healthcare professional must be aware of their responsibilities and contribute their unique expertise toward the patient's care plan, thereby fostering a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach.

Effective interprofessional communication facilitates seamless information exchange and collaboration among healthcare team members. Care coordination is crucial for managing the patient's journey from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up, thereby minimizing errors and enhancing patient safety. By embracing these skillful principles, strategy, ethics, responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and care coordination, healthcare professionals can deliver patient-centered care and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Ibraheem Rehman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Navid Mahabadi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Terrence Sanvictores declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Chaudhry Rehman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Rehman I, Mahabadi N, Sanvictores T, et al. Classical Conditioning. [Updated 2024 Sep 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Chronic Recording During Learning. [Methods for Neural Ensemble Re...] Review Chronic Recording During Learning. Sandler AJ. Methods for Neural Ensemble Recordings. 2008

- Pavlov's position toward Konorski and Miller's distinction between Pavlovian and motor conditioning paradigms. [Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1996] Pavlov's position toward Konorski and Miller's distinction between Pavlovian and motor conditioning paradigms. Windholz G, Wyrwicka W. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1996 Oct-Dec; 31(4):338-49.

- Eponymy, obscurity, Twitmyer, and Pavlov. [J Hist Behav Sci. 1982] Eponymy, obscurity, Twitmyer, and Pavlov. Coon DJ. J Hist Behav Sci. 1982 Jul; 18(3):255-62.

- Review From Pavlov to PTSD: the extinction of conditioned fear in rodents, humans, and anxiety disorders. [Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014] Review From Pavlov to PTSD: the extinction of conditioned fear in rodents, humans, and anxiety disorders. VanElzakker MB, Dahlgren MK, Davis FC, Dubois S, Shin LM. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014 Sep; 113:3-18. Epub 2013 Dec 7.

- Signalization and stimulus-substitution in Pavlov's theory of conditioning. [Span J Psychol. 2003] Signalization and stimulus-substitution in Pavlov's theory of conditioning. García-Hoz V. Span J Psychol. 2003 Nov; 6(2):168-76.

Recent Activity

- Classical Conditioning - StatPearls Classical Conditioning - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Learn More Psychology

- Behavioral Psychology

Pavlov's Dogs and Classical Conditioning

How pavlov's experiments with dogs demonstrated that our behavior can be changed using conditioning..

Permalink Print |

One of the most revealing studies in behavioral psychology was carried out by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) in a series of experiments today referred to as 'Pavlov's Dogs'. His research would become renowned for demonstrating the way in classical conditioning (also referred to as Pavlovian conditioning ) could be used to cultivate a particular association between the occurrence of one event in the anticipation of another.

- Conditioning

- Stimulus-Response Theory

- Reductionism in Psychology

- What Factors Affect Classical Conditioning?

- Imprinting and Relationships

Pavlov's Dog Experiments

Pavlov came across classical conditioning unintentionally during his research into animals' gastric systems. Whilst measuring the salivation rates of dogs, he found that they would produce saliva when they heard or smelt food in anticipation of feeding. This is a normal reflex response which we would expect to happen as saliva plays a role in the digestion of food.

Did You Know?

Psychologist Edwin Twitmyer at the University of Pennsylvania in the U.S. discovered classical conditioning at approximately the same time as Pavlov was conducting his research ( Coon, 1982 ). 1 However, the two were unaware of each other's research in this case of simultaneous discovery , and Pavlov received credit for the findings.

However, the dogs also began to salivate when events occurred which would otherwise be unrelated to feeding. By playing sounds to the dogs prior to feeding them, Pavlov showed that they could be conditioned to unconsciously associate neutral, unrelated events with being fed 2 .

Experiment Procedure

Pavlov's dogs were each placed in an isolated environment and restrained in a harness, with a food bowl in front of them and a device was used to measure the rate at which their saliva glands made secretions. These measurements would then be recorded onto a revolving drum so that Pavlov could monitor salivation rates throughout the experiments.

He found that the dogs would begin to salivate when a door was opened for the researcher to feed them.

This response demonstrated the basic principle of classical conditioning . A neutral event, such as opening a door (a neutral stimulus , NS) could be associated with another event that followed - in this case, being fed (known as the unconditioned stimulus , UCS). This association could be created through repeating the neutral stimulus along with the unconditioned stimulus, which would become a conditioned stimulus , leading to a conditioned response : salivation.

Pavlov continued his research and tested a variety of other neutral stimuli which would otherwise be unlinked to the receipt of food. These included precise tones produced by a buzzer, the ticking of a metronome and electric shocks .

The dogs would demonstrate a similar association between these events and the food that followed.

NEUTRAL STIMULUS (NS, eg. tone) > UNCONDITIONED STIMULUS (UCS, eg. receiving food)

when repeated leads to:

CONDITIONED STIMULUS (CS, eg. tone) > CONDITIONED RESPONSE (CR, eg. salivation)

The implications for Pavlov's findings are significant as they can be applied to many animals, including humans.

For example, when you first saw someone holding a balloon and a pin close to it, you may have watched in anticipation as they burst the balloon. After this had happened multiple times, you would associate holding the pin to the balloon with the 'bang' that followed. Like Pavlov's dogs, classical conditioning was leading you to associate a neutral stimulus (the pin approaching a balloon) with bursting of the balloon, leading to a conditioned response (flinching, wincing or plugging one's ears) to this now conditioned stimulus.

- Craik & Lockhart (1972) Levels of Processing Theory

Let us look now at some of the nuances of Pavlov's findings in relation to classical conditioning.

'Unconditioning' through experimental extinction

Once an animal has been inadvertently conditioned to produce a response to a stimulus, can this association ever be broken?

Pavlov presented the dogs with a tone which they would come to associate with food. He then played the tone but did not follow that by rewarding the dogs with food.

After he made the sound without food numerous times, the dogs' produced less saliva as the conditioning underwent experimental extinction - a case of 'unlearning' the association.

When experimental extinction occurs, is the association permanently broken?

Pavlov's research would suggest that it remains but is inactive after extinction, and can be re-activated by reinstating, for example, the food reward, as it was given during the original conditioning. This phenomenon is known as spontaneous recovery .

Forward Conditioning vs Backward Conditioning

During conditioning, it is important that the neutral stimulus (NS) is presented before the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) in order for learning to take place. This forward conditioning is more likely to lead to a conditioned response than when the neutral stimulus is presented after the conditioned stimulus has been provided ( backward conditioning ).

In the case of Pavlov's dogs, the tone must be played to the subject prior to the food being provided. Making a sound after the dogs have been fed may not lead to a conditioned association being made between the events.

Carr and Freeman (1919) attempted both forward and backward conditioning in rats, between a buzzer sound and closed doors in a maze. They found backward conditioning to be ineffective when compared to forward conditioning. 4

Delay Conditioning vs Trace Conditioning

We may use forward conditioning in one of two forms:

Delay Conditioning - when the unconditioned stimulus is provided prior to and during the unconditioned stimulus - there is a period of overlap where the neutral and unconditioned stimulus are given simultaneously, e.g. a buzzer sound begins, and after 10 seconds, food is given whilst the buzzer continues.

Trace Conditioning - when there is a delay after the unconditioned stimulus has been provided before the unconditioned stimulus is presented to the subject, e.g. buzzer sounds for 10 seconds, stops and after 10 seconds of silence (the trace interval ), food is presented.

Discussing delay conditioning, Pavlov (1927) asserted that the longer the delay between the stimuli, the more delayed the response would be 5 .

Temporal Conditioning

So far, we have looked at conditioning in which a neutral stimulus is key to eliciting a desired response. However, if an unconditioned stimulus is provided at regular intervals, even without a preceding neutral stimulus, animals' sense of timing will enable conditioning to take place, and a response may occur in time with the intervals.

For example, in a study in which rats were fed at either random or regular intervals, Kirkpatrick and Church (2003) found that the subjects underwent temporal conditioning in the anticipation of food when they were fed at set intervals. 6

Generalisation

Pavlov noticed that once neutral stimulus had been associated with an unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned stimulus could vary and the dogs would still generate a similar response. For example, once specific tone of buzzer sound was associated with food, differing toned buzzer sounds would solicit a conditioned response.

Nonetheless, the closer the stimulus was to the original stimulus used in conditioning, the clearer the response would be. This correlation between stimulus accuracy and response is referred to as a generalisation gradient , and has been demonstrated in studies such as Meulders et al (2013) . 7

Modern Classical Conditioning

Pavlov's dog experiments are still discussed today and have influenced many later ideas in psychology. The U.S. psychologist John B. Watson was impressed by Pavlov's findings and reproduced classical conditioning in the Little Albert Experiment (Watson, 1920), in which a subject was unethically conditioned to associate furry stimuli such as rabbits with a loud noise, and subsequently developed a fear of rats. 8

- Behavioral Approach

The numerous studies following the experiments, which have demonstrated classical conditioning using a variety of methods, also show the replicability of Pavlov's research, helping it to be recognised as an important unconscious influence of human behavior. This has helped the theory to be recognised and applied in many real life situations, from training dogs to creating associations in today's product advertisements.

Continue Reading

- Coon, D.J. (1982). Eponymy, obscurity, Twitmyer, and Pavlov. Journal of the History of Behavioral Science . 18 (3). 255-62.

- Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/ .

- Craik, F.I.M. and Lockhart, R.S. (1972). Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Visual Behavior . 11 (6). 671-684.

- Carr, H. and Freeman A. (1919). Time relationships in the formation of associations. Psychology Review . 26 (6). 335-353.

- Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/lecture6.htm .

- Kirkpatrick, K and Church, R.M. (2003). Tracking of the expected time to reinforcement in temporal conditioning processes. Learning & Behavior . 31 (1). 3-21.

- Meulders A, Vandebroek, N. Vervliet, B. and Vlaeyen, J.W.S. (2013). Generalization Gradients in Cued and Contextual Pain-Related Fear: An Experimental Study in Health Participants. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience , 7 (345). 1-12.

- Watson, J.B. and Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned Emotional Reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology . 3 (1). 1-14.

- Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review . (Watson, 1913). 20 . 158-177.

Which Archetype Are You?

Are You Angry?

Windows to the Soul

Are You Stressed?

Attachment & Relationships

Memory Like A Goldfish?

31 Defense Mechanisms

Slave To Your Role?

Are You Fixated?

Interpret Your Dreams

How to Read Body Language

How to Beat Stress and Succeed in Exams

More on Behavioral Psychology

Dressing To Impress

The psychology driving our clothing choices and how fashion affects your dating...

Fashion Psychology: What Clothes Say About You

Shock Therapy

Aversion therapy uses the principle that new behavior can be 'learnt' in order...

Immerse To Overcome?

If you jumped out of a plane, would you overcome your fear of heights?

Imprinting: Why First Impressions Matter

How first impressions from birth influence our relationship choices later in...

Bats & Goodwill

Why do we help other people? When Darwin introduced his theory of natural...

Sign Up for Unlimited Access

- Psychology approaches, theories and studies explained

- Body Language Reading Guide

- How to Interpret Your Dreams Guide

- Self Hypnosis Downloads

- Plus More Member Benefits

You May Also Like...

Nap for performance, psychology of color, making conversation, brainwashed, master body language, dark sense of humor linked to intelligence, why do we dream, persuasion with ingratiation, psychology guides.

Learn Body Language Reading

How To Interpret Your Dreams

Overcome Your Fears and Phobias

Psychology topics, learn psychology.

- Access 2,200+ insightful pages of psychology explanations & theories

- Insights into the way we think and behave

- Body Language & Dream Interpretation guides

- Self hypnosis MP3 downloads and more

- Eye Reading

- Stress Test

- Cognitive Approach

- Fight-or-Flight Response

- Neuroticism Test

© 2024 Psychologist World. Home About Contact Us Terms of Use Privacy & Cookies Hypnosis Scripts Sign Up

Ivan Pavlov and the Theory of Classical Conditioning

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Pavlovian Conditioning: Exploring the Science of Classical Learning

A bell rings, a dog salivates—this seemingly simple connection revolutionized our understanding of learning and behavior, thanks to the groundbreaking work of Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. Little did Pavlov know that his curious observations would spark a scientific revolution, forever changing the landscape of psychology and behavioral science.

Imagine, if you will, a laboratory bustling with activity, the air thick with the scent of determination and discovery. It’s here, amidst the clinking of glassware and the scribbling of notes, that Pavlov stumbled upon a phenomenon that would come to be known as classical conditioning. His work, initially focused on digestion in dogs, took an unexpected turn when he noticed something peculiar: his canine subjects began salivating not just at the sight of food, but at the mere sound of his footsteps approaching.

This serendipitous observation set the stage for a series of experiments that would unravel the mysteries of how organisms learn to associate stimuli with specific responses. Pavlov’s discovery laid the foundation for behaviorism, a psychological approach that dominated the field for decades and continues to influence our understanding of learning and behavior to this day.

The ABCs of Pavlovian Conditioning

At its core, Pavlovian conditioning, also known as classical conditioning , is a learning process that occurs through associations between environmental stimuli and naturally occurring stimuli. It’s a bit like teaching an old dog new tricks, except in this case, we’re teaching the dog’s nervous system to respond in new ways.

Let’s break it down into bite-sized pieces:

1. Unconditioned Stimulus (US): This is a stimulus that naturally triggers a response. Think of it as the “main course” in our conditioning meal.

2. Unconditioned Response (UR): The automatic, unlearned response to the US. It’s the body’s way of saying, “I know what to do with this!”

3. Conditioned Stimulus (CS): Initially a neutral stimulus, it becomes associated with the US through repeated pairings. It’s like the appetizer that starts to taste like the main course.

4. Conditioned Response (CR): The learned response to the CS, similar to the UR. It’s as if the body is saying, “I’ve seen this before, I know what comes next!”

The magic happens when these elements dance together in a carefully choreographed sequence. Through repeated pairings of the US and CS, the organism learns to associate the two, eventually responding to the CS alone as if it were the US. It’s like teaching your taste buds to water at the sound of a dinner bell—a culinary pavlovian party!

The Building Blocks of Behavioral Change

Now that we’ve whetted our appetite with the basics, let’s dive deeper into the key components that make Pavlovian conditioning tick. It’s like assembling a behavioral Lego set, with each piece playing a crucial role in the final structure.

First up, we have the neutral stimulus. This is the blank canvas upon which our conditioning masterpiece will be painted. It could be anything—a sound, a sight, even a smell—that initially elicits no particular response from the organism. But don’t be fooled by its innocuous nature; this little stimulus is about to become a star player in our behavioral drama.

Next comes acquisition, the process where the magic really happens . It’s during this phase that our neutral stimulus transforms into a conditioned stimulus, gradually gaining the power to elicit a response all on its own. It’s like watching a caterpillar metamorphose into a butterfly, except instead of wings, our stimulus gains the ability to make mouths water or hearts race.

But what goes up must come down, and that’s where extinction comes into play. If the CS is repeatedly presented without the US, the learned association begins to weaken. It’s nature’s way of saying, “Use it or lose it!” However, don’t count out that conditioned response just yet. Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, it can make a comeback through spontaneous recovery, suddenly reappearing after a period of extinction.

Last but not least, we have generalization and discrimination. These processes allow organisms to apply their learned responses to similar stimuli (generalization) or distinguish between similar stimuli to respond only to the specific CS (discrimination). It’s like having a behavioral Swiss Army knife, adaptable yet precise.

Flavors of Pavlovian Conditioning

Just as ice cream comes in various flavors, Pavlovian conditioning isn’t a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Let’s scoop into the different types:

1. Delay Conditioning: The simplest form, where the CS and US overlap, with the CS presented slightly before the US. It’s like the classic bell-before-food scenario in Pavlov’s experiments.

2. Trace Conditioning: Here, there’s a gap between the CS and US. It’s as if we’re playing a game of behavioral hide-and-seek, with the US popping up a short while after the CS disappears.

3. Simultaneous Conditioning: As the name suggests, the CS and US are presented at the same time. It’s a bit like a behavioral duet, with both stimuli singing in harmony.

4. Backward Conditioning: In this topsy-turvy version, the US comes before the CS. It’s like reading a story backwards—tricky, but not impossible!

Each type has its own unique characteristics and challenges, showcasing the versatility and complexity of classical conditioning. It’s a testament to the brain’s remarkable ability to form associations in various temporal arrangements.

Pavlov in the Real World

Now, you might be thinking, “That’s all well and good for dogs in a lab, but what about the real world?” Well, hold onto your hats, because Pavlovian conditioning is more prevalent in our daily lives than you might think!

Take behavior therapy, for instance. Therapists often use classical conditioning principles to help people overcome phobias. By gradually exposing a person to their fear (the CS) in a safe, controlled environment, and pairing it with relaxation techniques (the US), they can help rewire the brain’s response. It’s like giving your fear response a much-needed software update.

But it’s not just in therapy where Pavlov’s principles shine. Marketers and advertisers have long been hip to the power of classical conditioning. Ever wonder why that catchy jingle makes you crave a certain fast food? Or why the sight of a particular logo makes you feel warm and fuzzy? That’s classical conditioning at work, subtly influencing your preferences and behaviors.

In the realm of education, teachers often unknowingly employ Pavlovian techniques. The consistent pairing of praise with correct answers can condition students to feel good about learning, creating a positive association that can last a lifetime. It’s like planting seeds of knowledge in fertile, well-conditioned soil.

And let’s not forget our furry friends. Animal trainers rely heavily on classical conditioning principles to teach everything from basic obedience to complex tricks. That clever dog performing in the circus? You can bet Pavlov had a hand (or paw) in that!

The Flip Side of the Conditioning Coin

Now, before we get too carried away singing the praises of Pavlovian conditioning, it’s important to acknowledge that it’s not without its critics and limitations. After all, even the most beautiful rose has its thorns.

One of the main criticisms is that classical conditioning can oversimplify complex behaviors. Human beings, with our intricate cognitive processes and individual experiences, aren’t always as predictable as Pavlov’s dogs. It’s like trying to explain a symphony using only the notes of a single instrument—you might get the gist, but you’re missing a lot of the nuance.

Ethical concerns also arise, particularly in human and animal studies. The idea of manipulating behavior through conditioning can tread into murky moral waters. It’s a bit like having a behavioral superpower—with great power comes great responsibility.

Individual differences in conditioning are another wrinkle in the Pavlovian fabric. Not everyone responds to stimuli in the same way or at the same rate. Some people might condition quickly, while others might resist conditioning altogether. It’s like trying to bake a cake with ingredients that don’t always behave as expected—you might end up with something delicious, or you might end up with a culinary disaster.

Lastly, we can’t ignore the role of cognition in classical conditioning. Our thoughts, beliefs, and expectations can influence how we respond to conditioned stimuli . It’s as if our brains are constantly running their own little experiments, sometimes confirming and sometimes contradicting our conditioned responses.

The Legacy of a Ringing Bell

As we wrap up our journey through the fascinating world of Pavlovian conditioning, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on the enduring impact of Pavlov’s work. From that first curious observation of salivating dogs to the complex understanding we have today, classical conditioning has come a long way.

Pavlov’s discovery opened up new avenues of research and sparked countless debates in the field of psychology. Today, researchers continue to explore the intricacies of classical conditioning, uncovering new applications and refining our understanding of how learning occurs at a neural level. It’s like peeling an onion, with each layer revealing new insights and raising new questions.

The principles of Pavlovian conditioning have seeped into various aspects of our lives, often in ways we don’t even realize. From the strategies used in addiction treatment to the techniques employed in product marketing, the echoes of Pavlov’s bell can be heard far and wide.

Understanding classical conditioning can be a powerful tool in our personal and professional lives. It can help us recognize and potentially modify our own conditioned responses, making us more aware of the subtle influences that shape our behaviors and decisions. It’s like having a user manual for your own brain—a guide to the quirks and features of your personal operating system.

As we move forward, it’s clear that Pavlovian conditioning will continue to play a significant role in our understanding of learning and behavior. Who knows what new discoveries await us? Perhaps the next breakthrough is just around the corner, waiting for a curious mind to notice something unexpected, just as Pavlov did all those years ago.

So the next time you find yourself reaching for a snack at the sound of a commercial jingle, or feeling a flutter of nerves at a certain smell, take a moment to appreciate the complex conditioning processes at work. After all, we’re all a bit like Pavlov’s dogs, continually learning and adapting to the stimuli around us. And isn’t that something to salivate over?

References:

1. Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Oxford University Press.

2. Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151-160.

3. Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 485-494.

4. Domjan, M. (2005). Pavlovian Conditioning: A Functional Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 179-206.

5. Pearce, J. M., & Bouton, M. E. (2001). Theories of associative learning in animals. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 111-139.

6. Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford University Press.

7. Schachtman, T. R., & Reilly, S. (Eds.). (2011). Associative learning and conditioning theory: Human and non-human applications. Oxford University Press.

8. Rescorla, R. A., & Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory, 2, 64-99.

9. LeDoux, J. E. (2014). Coming to terms with fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(8), 2871-2878.

10. Fanselow, M. S., & Poulos, A. M. (2005). The neuroscience of mammalian associative learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 207-234.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Excitatory Conditioning: Enhancing Learning and Behavior Through Positive Reinforcement

Little Albert Experiment: A Landmark Study in Classical Conditioning

Antecedent Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behavior Through Environmental Cues

Rule-Governed Behavior: Shaping Actions Through ABA Principles

Intermittent Conditioning: Revolutionizing Fitness and Performance

Operant Conditioning Terms: A Comprehensive Guide to Behavioral Psychology

Conditioning: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Meaning and Applications

Acquisition Phase of Classical Conditioning: Key Principles and Applications

Modeling Conditioning: Techniques for Enhancing Model Performance and Stability

Subconscious Conditioning: Shaping Your Mind for Success and Well-being

Classical Conditioning

Learning objectives.

- Explain how classical conditioning occurs

- Identify the NS, UCS, UCR, CS, and CR in classical conditioning situations

Does the name Ivan Pavlov ring a bell? Even if you are new to the study of psychology, chances are that you have heard of Pavlov and his famous dogs.

Pavlov (1849–1936), a Russian scientist, performed extensive research on dogs and is best known for his experiments in classical conditioning (Figure 1). As we discussed briefly in the previous section, classical conditioning is a process by which we learn to associate stimuli and, consequently, to anticipate events.

Figure 1 . Ivan Pavlov’s research on the digestive system of dogs unexpectedly led to his discovery of the learning process now known as classical conditioning.

Pavlov came to his conclusions about how learning occurs completely by accident. Pavlov was a physiologist, not a psychologist. Physiologists study the life processes of organisms, from the molecular level to the level of cells, organ systems, and entire organisms. Pavlov’s area of interest was the digestive system (Hunt, 2007). In his studies with dogs, Pavlov measured the amount of saliva produced in response to various foods. Over time, Pavlov (1927) observed that the dogs began to salivate not only at the taste of food, but also at the sight of food, at the sight of an empty food bowl, and even at the sound of the laboratory assistants’ footsteps. Salivating to food in the mouth is reflexive, so no learning is involved. However, dogs don’t naturally salivate at the sight of an empty bowl or the sound of footsteps.