20.3 Electromagnetic Induction

Section learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how a changing magnetic field produces a current in a wire

- Calculate induced electromotive force and current

Teacher Support

The learning objectives in this section will help your students master the following standards:

- (G) investigate and describe the relationship between electric and magnetic fields in applications such as generators, motors, and transformers.

In addition, the OSX High School Physics Laboratory Manual addresses content in this section in the lab titled: Magnetism, as well as the following standards:

Section Key Terms

Changing magnetic fields.

In the preceding section, we learned that a current creates a magnetic field. If nature is symmetrical, then perhaps a magnetic field can create a current. In 1831, some 12 years after the discovery that an electric current generates a magnetic field, English scientist Michael Faraday (1791–1862) and American scientist Joseph Henry (1797–1878) independently demonstrated that magnetic fields can produce currents. The basic process of generating currents with magnetic fields is called induction ; this process is also called magnetic induction to distinguish it from charging by induction, which uses the electrostatic Coulomb force.

When Faraday discovered what is now called Faraday’s law of induction, Queen Victoria asked him what possible use was electricity. “Madam,” he replied, “What good is a baby?” Today, currents induced by magnetic fields are essential to our technological society. The electric generator—found in everything from automobiles to bicycles to nuclear power plants—uses magnetism to generate electric current. Other devices that use magnetism to induce currents include pickup coils in electric guitars, transformers of every size, certain microphones, airport security gates, and damping mechanisms on sensitive chemical balances.

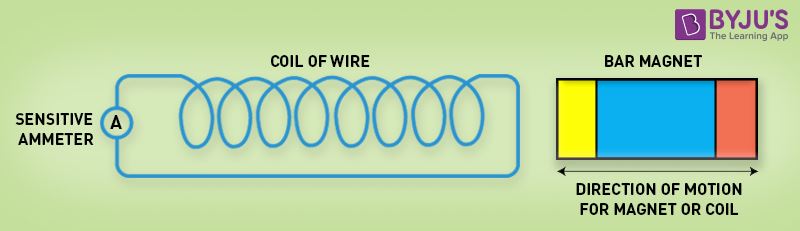

One experiment Faraday did to demonstrate magnetic induction was to move a bar magnet through a wire coil and measure the resulting electric current through the wire. A schematic of this experiment is shown in Figure 20.33 . He found that current is induced only when the magnet moves with respect to the coil. When the magnet is motionless with respect to the coil, no current is induced in the coil, as in Figure 20.33 . In addition, moving the magnet in the opposite direction (compare Figure 20.33 with Figure 20.33 ) or reversing the poles of the magnet (compare Figure 20.33 with Figure 20.33 ) results in a current in the opposite direction.

Virtual Physics

Faraday’s law.

Try this simulation to see how moving a magnet creates a current in a circuit. A light bulb lights up to show when current is flowing, and a voltmeter shows the voltage drop across the light bulb. Try moving the magnet through a four-turn coil and through a two-turn coil. For the same magnet speed, which coil produces a higher voltage?

- The sign of voltage will change because the direction of current flow will change by moving south pole of the magnet to the left.

- The sign of voltage will remain same because the direction of current flow will not change by moving south pole of the magnet to the left.

- The sign of voltage will change because the magnitude of current flow will change by moving south pole of the magnet to the left.

- The sign of voltage will remain same because the magnitude of current flow will not change by moving south pole of the magnet to the left.

Induced Electromotive Force

If a current is induced in the coil, Faraday reasoned that there must be what he called an electromotive force pushing the charges through the coil. This interpretation turned out to be incorrect; instead, the external source doing the work of moving the magnet adds energy to the charges in the coil. The energy added per unit charge has units of volts, so the electromotive force is actually a potential. Unfortunately, the name electromotive force stuck and with it the potential for confusing it with a real force. For this reason, we avoid the term electromotive force and just use the abbreviation emf , which has the mathematical symbol ε . ε . The emf may be defined as the rate at which energy is drawn from a source per unit current flowing through a circuit. Thus, emf is the energy per unit charge added by a source, which contrasts with voltage, which is the energy per unit charge released as the charges flow through a circuit.

To understand why an emf is generated in a coil due to a moving magnet, consider Figure 20.34 , which shows a bar magnet moving downward with respect to a wire loop. Initially, seven magnetic field lines are going through the loop (see left-hand image). Because the magnet is moving away from the coil, only five magnetic field lines are going through the loop after a short time Δ t Δ t (see right-hand image). Thus, when a change occurs in the number of magnetic field lines going through the area defined by the wire loop, an emf is induced in the wire loop. Experiments such as this show that the induced emf is proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic field. Mathematically, we express this as

where Δ B Δ B is the change in the magnitude in the magnetic field during time Δ t Δ t and A is the area of the loop.

Note that magnetic field lines that lie in the plane of the wire loop do not actually pass through the loop, as shown by the left-most loop in Figure 20.35 . In this figure, the arrow coming out of the loop is a vector whose magnitude is the area of the loop and whose direction is perpendicular to the plane of the loop. In Figure 20.35 , as the loop is rotated from θ = 90° θ = 90° to θ = 0° , θ = 0° , the contribution of the magnetic field lines to the emf increases. Thus, what is important in generating an emf in the wire loop is the component of the magnetic field that is perpendicular to the plane of the loop, which is B cos θ . B cos θ .

This is analogous to a sail in the wind. Think of the conducting loop as the sail and the magnetic field as the wind. To maximize the force of the wind on the sail, the sail is oriented so that its surface vector points in the same direction as the winds, as in the right-most loop in Figure 20.35 . When the sail is aligned so that its surface vector is perpendicular to the wind, as in the left-most loop in Figure 20.35 , then the wind exerts no force on the sail.

Thus, taking into account the angle of the magnetic field with respect to the area, the proportionality E ∝ Δ B / Δ t E ∝ Δ B / Δ t becomes

Another way to reduce the number of magnetic field lines that go through the conducting loop in Figure 20.35 is not to move the magnet but to make the loop smaller. Experiments show that changing the area of a conducting loop in a stable magnetic field induces an emf in the loop. Thus, the emf produced in a conducting loop is proportional to the rate of change of the product of the perpendicular magnetic field and the loop area

where B cos θ B cos θ is the perpendicular magnetic field and A is the area of the loop. The product B A cos θ B A cos θ is very important. It is proportional to the number of magnetic field lines that pass perpendicularly through a surface of area A . Going back to our sail analogy, it would be proportional to the force of the wind on the sail. It is called the magnetic flux and is represented by Φ Φ .

The unit of magnetic flux is the weber (Wb), which is magnetic field per unit area, or T/m 2 . The weber is also a volt second (Vs).

The induced emf is in fact proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic flux through a conducting loop.

Finally, for a coil made from N loops, the emf is N times stronger than for a single loop. Thus, the emf induced by a changing magnetic field in a coil of N loops is

The last question to answer before we can change the proportionality into an equation is “In what direction does the current flow?” The Russian scientist Heinrich Lenz (1804–1865) explained that the current flows in the direction that creates a magnetic field that tries to keep the flux constant in the loop. For example, consider again Figure 20.34 . The motion of the bar magnet causes the number of upward-pointing magnetic field lines that go through the loop to decrease. Therefore, an emf is generated in the loop that drives a current in the direction that creates more upward-pointing magnetic field lines. By using the right-hand rule, we see that this current must flow in the direction shown in the figure. To express the fact that the induced emf acts to counter the change in the magnetic flux through a wire loop, a minus sign is introduced into the proportionality ε ∝ Δ Φ / Δ t . ε ∝ Δ Φ / Δ t . , which gives Faraday’s law of induction.

Lenz’s law is very important. To better understand it, consider Figure 20.36 , which shows a magnet moving with respect to a wire coil and the direction of the resulting current in the coil. In the top row, the north pole of the magnet approaches the coil, so the magnetic field lines from the magnet point toward the coil. Thus, the magnetic field B → mag = B mag ( x ^ ) B → mag = B mag ( x ^ ) pointing to the right increases in the coil. According to Lenz’s law, the emf produced in the coil will drive a current in the direction that creates a magnetic field B → coil = B coil ( − x ^ ) B → coil = B coil ( − x ^ ) inside the coil pointing to the left. This will counter the increase in magnetic flux pointing to the right. To see which way the current must flow, point your right thumb in the desired direction of the magnetic field B → coil, B → coil, and the current will flow in the direction indicated by curling your right fingers. This is shown by the image of the right hand in the top row of Figure 20.36 . Thus, the current must flow in the direction shown in Figure 4(a) .

In Figure 4(b) , the direction in which the magnet moves is reversed. In the coil, the right-pointing magnetic field B → mag B → mag due to the moving magnet decreases. Lenz’s law says that, to counter this decrease, the emf will drive a current that creates an additional right-pointing magnetic field B → coil B → coil in the coil. Again, point your right thumb in the desired direction of the magnetic field, and the current will flow in the direction indicate by curling your right fingers ( Figure 4(b) ).

Finally, in Figure 4(c) , the magnet is reversed so that the south pole is nearest the coil. Now the magnetic field B → mag B → mag points toward the magnet instead of toward the coil. As the magnet approaches the coil, it causes the left-pointing magnetic field in the coil to increase. Lenz’s law tells us that the emf induced in the coil will drive a current in the direction that creates a magnetic field pointing to the right. This will counter the increasing magnetic flux pointing to the left due to the magnet. Using the right-hand rule again, as indicated in the figure, shows that the current must flow in the direction shown in Figure 4(c) .

Faraday’s Electromagnetic Lab

This simulation proposes several activities. For now, click on the tab Pickup Coil, which presents a bar magnet that you can move through a coil. As you do so, you can see the electrons move in the coil and a light bulb will light up or a voltmeter will indicate the voltage across a resistor. Note that the voltmeter allows you to see the sign of the voltage as you move the magnet about. You can also leave the bar magnet at rest and move the coil, although it is more difficult to observe the results.

- Yes, the current in the simulation flows as shown because the direction of current is opposite to the direction of flow of electrons.

- No, current in the simulation flows in the opposite direction because the direction of current is same to the direction of flow of electrons.

Watch Physics

Induced current in a wire.

This video explains how a current can be induced in a straight wire by moving it through a magnetic field. The lecturer uses the cross product , which a type of vector multiplication. Don’t worry if you are not familiar with this, it basically combines the right-hand rule for determining the force on the charges in the wire with the equation F = q v B sin θ . F = q v B sin θ .

Grasp Check

What emf is produced across a straight wire 0.50 m long moving at a velocity of (1.5 m/s) x ^ x ^ through a uniform magnetic field (0.30 T) ẑ ? The wire lies in the ŷ -direction. Also, which end of the wire is at the higher potential—let the lower end of the wire be at y = 0 and the upper end at y = 0.5 m)?

- 0.15 V and the lower end of the wire will be at higher potential

- 0.15 V and the upper end of the wire will be at higher potential

- 0.075 V and the lower end of the wire will be at higher potential

- 0.075 V and the upper end of the wire will be at higher potential

Worked Example

Emf induced in conducing coil by moving magnet.

Imagine a magnetic field goes through a coil in the direction indicated in Figure 20.37 . The coil diameter is 2.0 cm. If the magnetic field goes from 0.020 to 0.010 T in 34 s, what is the direction and magnitude of the induced current? Assume the coil has a resistance of 0.1 Ω. Ω.

Use the equation ε = − N Δ Φ / Δ t ε = − N Δ Φ / Δ t to find the induced emf in the coil, where Δ t = 34 s Δ t = 34 s . Counting the number of loops in the solenoid, we find it has 16 loops, so N = 16 . N = 16 . Use the equation Φ = B A cos θ Φ = B A cos θ to calculate the magnetic flux

where d is the diameter of the solenoid and we have used cos 0° = 1 . cos 0° = 1 . Because the area of the solenoid does not vary, the change in the magnetic of the flux through the solenoid is

Once we find the emf, we can use Ohm’s law, ε = I R , ε = I R , to find the current.

Finally, Lenz’s law tells us that the current should produce a magnetic field that acts to oppose the decrease in the applied magnetic field. Thus, the current should produce a magnetic field to the right.

Combining equations ε = − N Δ Φ / Δ t ε = − N Δ Φ / Δ t and Φ = B A cos θ Φ = B A cos θ gives

Solving Ohm’s law for the current and using this result gives

Lenz’s law tells us that the current must produce a magnetic field to the right. Thus, we point our right thumb to the right and curl our right fingers around the solenoid. The current must flow in the direction in which our fingers are pointing, so it enters at the left end of the solenoid and exits at the right end.

Let’s see if the minus sign makes sense in Faraday’s law of induction. Define the direction of the magnetic field to be the positive direction. This means the change in the magnetic field is negative, as we found above. The minus sign in Faraday’s law of induction negates the negative change in the magnetic field, leaving us with a positive current. Therefore, the current must flow in the direction of the magnetic field, which is what we found.

Now try defining the positive direction to be the direction opposite that of the magnetic field, that is positive is to the left in Figure 20.37 . In this case, you will find a negative current. But since the positive direction is to the left, a negative current must flow to the right, which again agrees with what we found by using Lenz’s law.

Magnetic Induction due to Changing Circuit Size

The circuit shown in Figure 20.38 consists of a U-shaped wire with a resistor and with the ends connected by a sliding conducting rod. The magnetic field filling the area enclosed by the circuit is constant at 0.01 T. If the rod is pulled to the right at speed v = 0.50 m/s, v = 0.50 m/s, what current is induced in the circuit and in what direction does the current flow?

We again use Faraday’s law of induction, E = − N Δ Φ Δ t , E = − N Δ Φ Δ t , although this time the magnetic field is constant and the area enclosed by the circuit changes. The circuit contains a single loop, so N = 1 . N = 1 . The rate of change of the area is Δ A Δ t = v ℓ . Δ A Δ t = v ℓ . Thus the rate of change of the magnetic flux is

where we have used the fact that the angle θ θ between the area vector and the magnetic field is 0°. Once we know the emf, we can find the current by using Ohm’s law. To find the direction of the current, we apply Lenz’s law.

Faraday’s law of induction gives

Solving Ohm’s law for the current and using the previous result for emf gives

As the rod slides to the right, the magnetic flux passing through the circuit increases. Lenz’s law tells us that the current induced will create a magnetic field that will counter this increase. Thus, the magnetic field created by the induced current must be into the page. Curling your right-hand fingers around the loop in the clockwise direction makes your right thumb point into the page, which is the desired direction of the magnetic field. Thus, the current must flow in the clockwise direction around the circuit.

Is energy conserved in this circuit? An external agent must pull on the rod with sufficient force to just balance the force on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field—recall that F = I ℓ B sin θ . F = I ℓ B sin θ . The rate at which this force does work on the rod should be balanced by the rate at which the circuit dissipates power. Using F = I ℓ B sin θ , F = I ℓ B sin θ , the force required to pull the wire at a constant speed v is

where we used the fact that the angle θ θ between the current and the magnetic field is 90° . 90° . Inserting our expression above for the current into this equation gives

The power contributed by the agent pulling the rod is F pull v , or F pull v , or

The power dissipated by the circuit is

We thus see that P pull + P dissipated = 0 , P pull + P dissipated = 0 , which means that power is conserved in the system consisting of the circuit and the agent that pulls the rod. Thus, energy is conserved in this system.

Practice Problems

The magnetic flux through a single wire loop changes from 3.5 Wb to 1.5 Wb in 2.0 s. What emf is induced in the loop?

What is the emf for a 10-turn coil through which the flux changes at 10 Wb/s?

Check Your Understanding

- An electric current is induced if a bar magnet is placed near the wire loop.

- An electric current is induced if a wire loop is wound around the bar magnet.

- An electric current is induced if a bar magnet is moved through the wire loop.

- An electric current is induced if a bar magnet is placed in contact with the wire loop.

- Induced current can be created by changing the size of the wire loop only.

- Induced current can be created by changing the orientation of the wire loop only.

- Induced current can be created by changing the strength of the magnetic field only.

- Induced current can be created by changing the strength of the magnetic field, changing the size of the wire loop, or changing the orientation of the wire loop.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute Texas Education Agency (TEA). The original material is available at: https://www.texasgateway.org/book/tea-physics . Changes were made to the original material, including updates to art, structure, and other content updates.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Physics

- Publication date: Mar 26, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/20-3-electromagnetic-induction

© Jun 7, 2024 Texas Education Agency (TEA). The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Electromagnetism

- Faradays Law

Faraday’s Laws of Electromagnetic Induction

Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction, also known as Faraday’s law, is the basic law of electromagnetism which helps us predict how a magnetic field would interact with an electric circuit to produce an electromotive force (EMF). This phenomenon is known as electromagnetic induction.

Michael Faraday proposed the laws of electromagnetic induction in the year 1831. Faraday’s law or the law of electromagnetic induction is the observation or results of the experiments conducted by Faraday. He performed three main experiments to discover the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction.

Faraday’s Laws of Electromagnetic Induction

Faraday’s Laws of Electromagnetic Induction consists of two laws. The first law describes the induction of emf in a conductor and the second law quantifies the emf produced in the conductor. In the next few sections, let us learn these laws in detail.

Faraday’s First Law of Electromagnetic Induction

The discovery and understanding of electromagnetic induction are based on a long series of experiments carried out by Faraday and Henry. From the experimental observations, Faraday concluded that an emf is induced when the magnetic flux across the coil changes with time. Therefore, Faraday’s first law of electromagnetic induction states the following:

Whenever a conductor is placed in a varying magnetic field, an electromotive force is induced. If the conductor circuit is closed, a current is induced, which is called induced current.

Changing the Magnetic Field Intensity in a Closed Loop

Magnetic field intensity in a closed loop

Mentioned here are a few ways to change the magnetic field intensity in a closed loop:

- By rotating the coil relative to the magnet.

- By moving the coil into or out of the magnetic field.

- By changing the area of a coil placed in the magnetic field.

- By moving a magnet towards or away from the coil.

Faraday’s Second Law of Electromagnetic Induction

Faraday’s second law of electromagnetic induction states that

The induced emf in a coil is equal to the rate of change of flux linkage.

The flux linkage is the product of the number of turns in the coil and the flux associated with the coil. The formula of Faraday’s law is given below:

Where ε is the electromotive force, Φ is the magnetic flux, and N is the number of turns.

Learn more about Faraday’s Law of induction and the relationship between the electric circuit and magnetic field by watching this engaging video from BYJU’S.

The German physicist Heinrich Friedrich Lenz deduced a rule known as Lenz’s law that describes the polarity of the induced emf.

Lenz’s law states that “The polarity of induced emf is such that it tends to produce a current which opposes the change in magnetic flux that produced it.”

The negative sign in the formula represents this effect. Thus, the negative sign indicates that the direction of the induced emf and the change in the direction of magnetic fields have opposite signs.

Read more: Lenz’s law

Faraday’s Law Derivation

Consider a magnet approaching a coil. Consider two-time instances T 1 and T 2 .

Flux linkage with the coil at the time T 1 is given by NΦ 1 .

Flux linkage with the coil at the time T 2 is given by NΦ 2

Change in the flux linkage is given by

N(Φ 2 – Φ 1 )

Let us consider this change in flux linkage as

Φ = Φ 2 – Φ 1

Hence, the change in flux linkage is given by

The rate of change of flux linkage is given by

Taking the derivative of the above equation, we get

According to Faraday’s second law of electromagnetic induction, we know that the induced emf in a coil is equal to the rate of change of flux linkage. Therefore,

Considering Lenz’s law,

From the above equation, we can conclude the following

- Increase in the number of turns in the coil increases the induced emf

- Increasing the magnetic field strength increases the induced emf

- Increasing the speed of the relative motion between the coil and the magnet, results in the increased emf

Faraday’s Experiment: Relationship Between Induced EMF and Flux

- In the first experiment, he proved that when the strength of the magnetic field is varied, only then current is induced. An ammeter was connected to a loop of wire; the ammeter deflected when a magnet was moved towards the wire.

In the second experiment, he proved that passing a current through an iron rod would make it electromagnetic. He observed that when a relative motion exists between the magnet and the coil, an electromotive force will be induced. When the magnet was held stationary about its axis, no electromotive force was observed, but when the magnet was rotated about its own axis then the induced electromotive force was produced. Thus, there was no deflection in the ammeter when the magnet was held stationary.

While conducting the third experiment, he recorded that the galvanometer did not show any deflection and no induced current was produced in the coil when the coil was kept away in a stationary magnetic field. The ammeter deflected in the opposite direction when the magnet was kept away from the loop.

Summarising the above points in a table, we have mapped out the relationship between the position of the magnet and the deflection in the Galvanometer.

Conclusion:

After conducting all the experiments, Faraday finally concluded that if relative motion existed between a conductor and a magnetic field, the flux linkage with a coil changed and this change in flux produced a voltage across a coil.

Faraday law basically states, “when the magnetic flux or the magnetic field changes with time, the electromotive force is produced”. Additionally, Michael Faraday also formulated two laws on the basis of the above experiments.

The below videos help to revise the chapter Magnetic Effects of Electric Current Class 10

Applications of faraday’s law.

Following are the fields where Faraday’s law finds applications:

- Electrical equipment like transformers works on the basis of Faraday’s law.

- Induction cooker works on the basis of mutual induction, which is based on the principle of Faraday’s law.

- By inducing an electromotive force into an electromagnetic flowmeter, the velocity of the fluids is recorded.

- Electric guitar and electric violin are musical instruments that find an application of Faraday’s law.

- Maxwell’s equation is based on the converse of Faraday’s laws which states that a change in the magnetic field brings a change in the electric field.

Frequently Asked Questions – FAQs

What does faraday’s first law of electromagnetic induction state.

Faraday’s first law of electromagnetic induction states, “Whenever a conductor is placed in a varying magnetic field, an electromotive force is induced. Likewise, if the conductor circuit is closed, a current is induced, which is called induced current.”

What does Faraday’s Second Law of Electromagnetic Induction state?

Why are faraday’s laws important, what does the negative sign indicate in faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction formula, what is meant by emf.

Stay tuned with BYJU’S for more such interesting articles. Also, register to “BYJU’S – The Learning App” for loads of interactive, engaging Physics-related videos and unlimited academic assist.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Physics related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

I am an older fellow trying to learn; and this is a big help to me. Thanks from; r c

The explanation is clear cut. So its so helpful for me to learn .THANK YOU from JB

A nice piece of revision material for exams. Thanks bro. I’m grateful

Differential Form of Maxwell Equations please explain this topic

Refer to the article below:

https://byjus.com/physics/maxwells-equations/

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Faraday's Law Of Induction: Definition, Formula & Examples

Around the turn of the 19th century, physicists were making a lot of progress in understanding the laws of electromagnetism, and Michael Faraday was one of the true pioneers in the area. Not long after it was discovered that an electric current creates a magnetic field, Faraday performed some now-famous experiments to work out if the reverse was true: Could magnetic fields induce a current?

Faraday's experiment showed that while magnetic fields alone couldn't induce current flows, a changing magnetic field (or, more precisely, a changing magnetic flux ) could.

The result of these experiments is quantified in Faraday's law of induction , and it's one of Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. This makes it one of the most important equations to understand and learn to use when you're studying electromagnetism.

Magnetic Flux

The concept of magnetic flux is crucial to understanding Faraday's law, because it relates flux changes to the induced electromotive force (EMF, commonly called voltage ) in the coil of wire or electric circuit. In simple terms, magnetic flux describes the flow of the magnetic field through a surface (although this "surface" isn't really a physical object; it's really just an abstraction to help quantify the flux), and you can imagine it more easily if you think about how many magnetic field lines are passing through a surface area A . Formally, it's defined as:

\(ϕ = \bm{B ∙ A} = BA \cos (θ)\)

Where B is the magnetic field strength (the magnetic flux density per unit area) in teslas (T), A is the area of the surface, and θ is the angle between the "normal" to the surface area (i.e., the line perpendicular to the surface) and B , the magnetic field. The equation basically says that a stronger magnetic field and a bigger area lead to more flux, along with a field aligned with the normal to the surface in question.

The ** B ∙ A ** in the equation is a scalar product (i.e., a "dot product") of vectors, which is a special mathematical operation for vectors (i.e., quantities with both a magnitude or "size" and a direction); however, the version with cos ( θ ) and the magnitudes is the same operation.

This simple version works when the magnetic field is uniform (or can be approximated as such) across A , but there is a more complicated definition for cases when the field isn't uniform. This involves integral calculus, which is a bit more complicated but something you'll need to learn if you're studying electromagnetism anyway:

\(ϕ = \int \bm{B} ∙ d\bm{A}\)

The SI unit of magnetic flux is the weber (Wb), where 1 Wb = T m 2 .

Michael Faraday’s Experiment

The famous experiment performed by Michael Faraday lays the groundwork for Faraday's law of induction and conveys the key point that shows the effect of flux changes on the electromotive force and consequent electric current induced.

The experiment itself is also quite straightforward, and you can even replicate it for yourself: Faraday wrapped an insulated conductive wire around a cardboard tube, and connected this to a voltmeter. A bar magnet was used for the experiment, first at rest near the coil, then moving towards the coil, then passing through the middle of the coil and then moving out of the coil and further away.

The voltmeter (a device that deduces voltage using a sensitive galvanometer) recorded the EMF generated in the wire, if any, during the experiment. Faraday found that when the magnet was at rest close to the coil, no current was induced in the wire. However, when the magnet was moving, the situation was very different: On the approach to the coil, there was some EMF measured, and it increased until it reached the center of the coil. The voltage reversed in sign when the magnet passed through the center point of the coil, and then it declined as the magnet moved away from the coil.

Faraday's experiment was really simple, but all of the key points it demonstrated are still in use in countless pieces of technology today, and the results were immortalized as one of Maxwell's equations.

Faraday’s Law

Faraday's law of induction states that the induced EMF (i.e., electromotive force or voltage, denoted by the symbol E ) in a coil of wire is given by:

\(E = −N \frac{∆ϕ}{∆t}\)

Where ϕ is the magnetic flux (as defined above), N is the number of turns in the coil of wire (so N = 1 for a simple loop of wire) and t is time. The SI unit of E is volts, since it's an EMF induced in the wire. In words, the equation tells you that you can create an induced EMF in a coil of wire either by changing the cross-sectional area A of the loop in the field, the strength of the magnetic field B , or the angle between the area and the magnetic field.

The delta symbols (∆) simply mean "change in," and so it tells you that the induced EMF is directly proportional to the corresponding rate of change of magnetic flux. This is more accurately expressed through a derivative, and often the N is dropped, and so Faraday's law can also be expressed as:

\(E = −\frac{dϕ}{dt}\)

In this form, you'll need to find out the time-dependence of either the magnetic flux density per unit area ( B ), the cross-sectional area of the loop A, or the angle between the normal to the surface and the magnetic field ( θ ), but once you do, this can be a much more useful expression for calculating the induced EMF.

Lenz's law is essentially an extra piece of detail in Faraday's law, encompassed by the minus sign in the equation and basically telling you the direction in which the induced current flows. It can be simply stated as: The induced current flows in a direction that opposes the change in magnetic flux that caused it. This means that if the change in magnetic flux was an increase in magnitude with no change in direction, the current will flow in a direction that will create a magnetic field in the opposite direction to the field lines of the original field.

The right-hand rule (or the right-hand grip rule, more specifically) can be used to determine the direction of the current that results from Faraday's law. Once you've worked out the direction of the new magnetic field based on the rate of change of magnetic flux of the original field, you point the thumb of your right hand in that direction. Allow your fingers to curl inwards as if you're making a fist; the direction your fingers move in is the direction of the induced current in the loop of wire.

Examples of Faraday’s Law: Moving Into a Field

Seeing Faraday's law put into practice will help you see how the law works when applied to real-world situations. Imagine you have a field pointing directly forwards, with a constant strength of B = 5 T, and a square single-stranded (i.e., N = 1) loop of wire with sides of length 0.1 m, making a total area A = 0.1 m × 0.1 m = 0.01 m 2 .

The square loop moves into the region of the field, traveling in the x direction at a rate of 0.02 m/s. This means that over a period of ∆ t = 5 seconds, the loop will go from being completely out of the field to completely inside it, and the normal to the field will be aligned with the magnetic field at all times (so θ = 0).

This means that the area in the field changes by ∆ A = 0.01 m 2 in t = 5 seconds. So the change in magnetic flux is:

\(\begin{aligned} ∆ϕ &= B∆A \cos (θ) \ &= 5 \text{ T} × 0.01 \text{ m}^2 × \cos (0) \ &= 0.05 \text{ Wb} \end{aligned}\)

Faraday's law states:

And so, with N = 1, ∆ ϕ = 0.05 Wb and ∆ t = 5 seconds:

\(\begin{aligned} E &= −N \frac{∆ϕ}{∆t}\ &= − 1 ×\frac{0.05 \text{ Wb}}{5} \ &= − 0.01 \text{ V} \end{aligned}\)

Examples of Faraday’s Law: Rotating Loop in a Field

Now consider a circular loop with area 1 m 2 and three turns of wire ( N = 3) rotating in a magnetic field with a constant magnitude of 0.5 T and a constant direction.

In this case, while the area of the loop A inside the field will remain constant and the field itself won't change, the angle of the loop with respect to the field is constantly changing. The rate of change of magnetic flux is the important thing, and in this case it's useful to use the differential form of Faraday's law. So we can write:

\(E = −N \frac{dϕ}{dt}\)

The magnetic flux is given by:

\(ϕ = BA \cos (θ)\)

But it's constantly changing, so the flux at any given time t – where we assume it starts at an angle of θ = 0 (i.e., aligned with the field) – is given by:

\(ϕ = BA \cos (ωt)\)

Where ω is the angular velocity.

Combining these gives:

\(\begin{aligned} E &= −N \frac{d}{dt} BA \cos (ωt) \ &= −NBA \frac{d}{dt} \cos (ωt) \end{aligned}\)

Now this can be differentiated to give:

\(E = NBAω \sin (ωt)\)

This formula is now ready to answer the question at any given time t , but it's clear from the formula that the faster the coil rotates (i.e., the higher the value of ω ), the greater the induced EMF. If the angular velocity ω = 2π rad/s, and you evaluate the result at 0.25 s, this gives:

\(\begin{aligned} E &= NBAω \sin (ωt) \ &= 3 × 0.5 \text{ T} × 1 \text{ m}^2 × 2π \text{ rad/s} × \sin (π /2) \ &= 9.42 \text{ V} \end{aligned}\)

Real World Applications of Faraday’s Law

Because of Faraday's law, any conductive object in the presence of a changing magnetic flux will have currents induced in it. In a loop of wire, these can flow in a circuit, but in a solid conductor, little loops of current called eddy currents form.

An eddy current is a small loop of current that flows in a conductor, and in many cases engineers work to reduce these because they're essentially wasted energy; however, they can be used productively in things like magnetic braking systems.

Traffic lights are an interesting real-world application of Faraday's law, because they use wire loops to detect the effect of the induced magnetic field. Under the road, loops of wire containing alternating current generate a changing magnetic field, and when your car drives over one of them, this induces eddy currents in the car. By Lenz's law, these currents generate an opposing magnetic field, which then impacts the current in the original wire loop. This impact on the original wire loop indicates the presence of a car, and then (hopefully, if you're mid-commute!) triggers the lights to change.

Electric generators are among the most useful applications of Faraday's law. The example of a rotating wire loop in a constant magnetic field basically tells you how they work: The motion of the coil generates a changing magnetic flux through the coil, which switches in direction every 180 degrees and thereby creates an alternating current . Although it – of course – requires work to generate the current, this allows you to turn mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- Georgia State University: HyperPhysics: Faraday's Law

- Georgia State University: HyperPhysics: Rotational Quantities

- University of Texas: Faraday's Law

- Lumen: Magnetic Flux, Induction, and Faraday's Law

- Khan Academy: What Is Faraday's Law?

- University of Tennessee at Knoxville: Faraday's Law

- Federal Highway Administration: Traffic Detector Handbook – Chapter 2: Sensor Technology

- Diamond Traffic: Inductive Loops

Cite This Article

Johnson, Lee. "Faraday's Law Of Induction: Definition, Formula & Examples" sciencing.com , https://www.sciencing.com/faradays-law-of-induction-definition-formula-examples-13721429/. 28 December 2020.

Johnson, Lee. (2020, December 28). Faraday's Law Of Induction: Definition, Formula & Examples. sciencing.com . Retrieved from https://www.sciencing.com/faradays-law-of-induction-definition-formula-examples-13721429/

Johnson, Lee. Faraday's Law Of Induction: Definition, Formula & Examples last modified August 30, 2022. https://www.sciencing.com/faradays-law-of-induction-definition-formula-examples-13721429/

Recommended

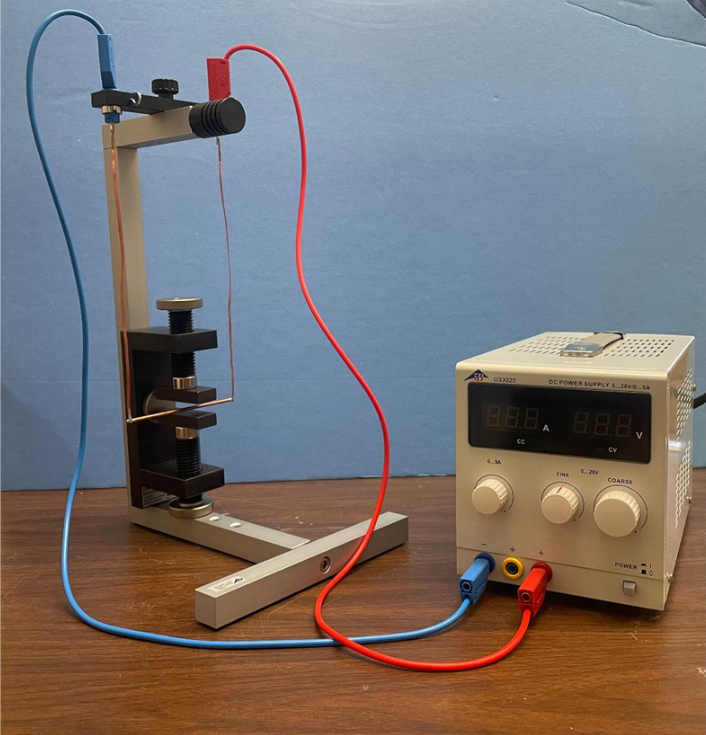

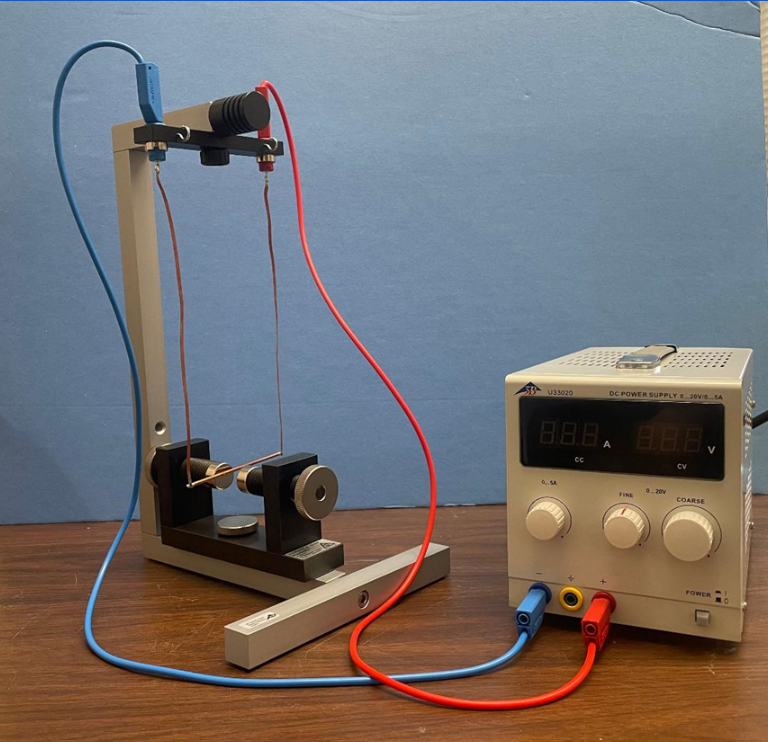

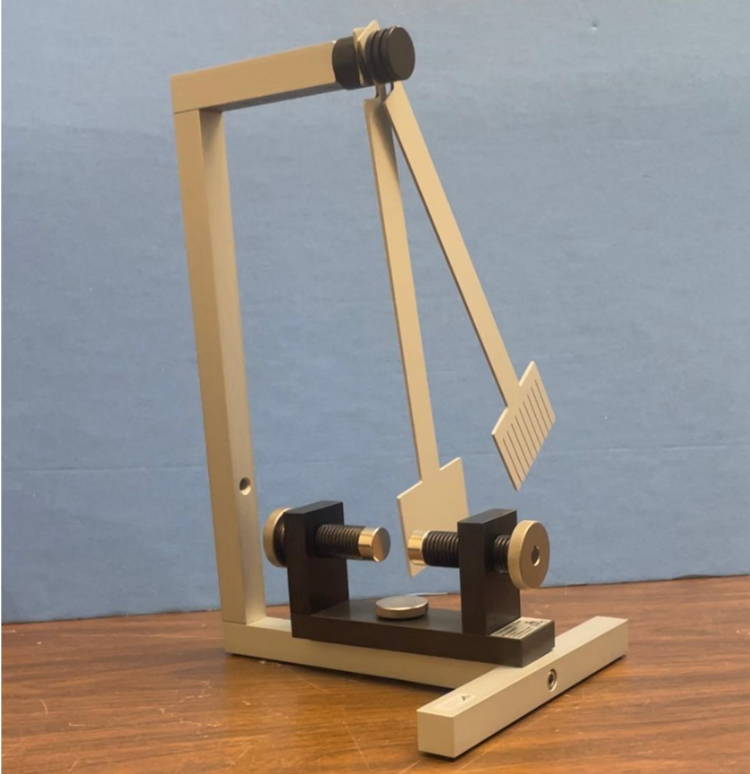

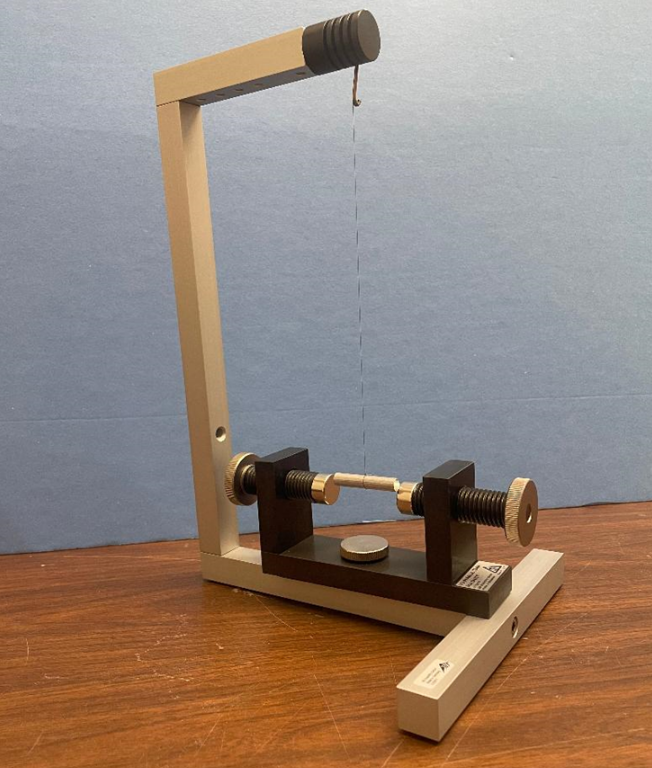

Induced Currents and Forces: Electromagnetic Experiment

Make sure to add a note of which experiment you want when requesting!! Different experiments require different set-ups.

Concepts Conveyed:

- Behavior of a current-carrying conductor in a magnetic field (Experiment 1)

- Induced eddy currents (Experiment 2)

- Diamagnetism and paramagnetism (Experiment 3)

Instructions

- Note: For every experiment, make sure that the bars and the entire set up are aligned properly because this can affect the position of the rods, copper wire, and pendulums.

Experiment 1a: Induced Force on Current in Wire

- Use the adjustable silver screw at the center of the magnet attachment to attach the magnet-screw system to the vertical bar of the stand. The copper wire should be suspended in between the magnets by screwing its bar onto the top of the upper bar of the stand.

- Plug in the blue and red wires from the 20V/5A power supply into the copper wires.

- Slowly increase the current (in A) through the wire, not exceeding 6A . The conductor swing should displace either to the right or left. As the current increases, the swing should displace a greater distance.

Experiment 1b: Lorentz Force

- Attach the magnet-screw system to the horizontal bottom bar. The copper wire is suspended in between the magnets by screwing its bar onto the bottom of the upper bar of the stand (use the first hole on the top silver bar to screw the bar).

- This time, increasing the current in the wire does not displace the conductor swing in any direction. This is because the Lorenz force does not act in the direction of the magnetic field or current flow.

Experiment 2: Eddy Current Pendulum

- Remove the two magnets and adjust the magnet-screw system to be closer together.

- Hang the solid pendulum and slotted pendulum onto any two slots on the pendulum axle mount. The magnet-screw system is attached to the horizontal bar, as in Experiment 1b.

- Displace the pendulums at the same angle and release.

- The solid pendulum should come to a full stop before the slotted pendulum does. This is because the slotted pendulum does not allow for the buildup of eddy currents.

Experiment 3: Magnetic Properties of Materials

- The setup of the magnet system is identical to experiment 2. Instead of using the pendulums, we will instead hang the glass or aluminum rod. You can use any slot from the black axle mount, just make sure to adjust the magnet screw system accordingly.

- Suspending the glass rod between the magnets will cause it to rotate one way and then the other.

- Suspending the aluminum rod will cause it to rotate completely before stopping parallel to the horizontal bar (in the direction of the magnetic field).

- Explanation: The rods align themselves in the magnetic field. Due to the different materials, their relative permeabilities are different. These differing permeabilities cause differing flux densities in each rod.

Demo Staff:

- Ensure that the setup is aligned properly. To do this, setup experiment 3 and ensure the center of mass of the rods are aligned with the magnet-screw system.

Last updated on April 10, 2024

- Sign in / Register

- Administration

- My Bookmarks

- My Contributions

- Activity Review

- Edit profile

The PhET website does not support your browser. We recommend using the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Edge.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

One experiment Faraday did to demonstrate magnetic induction was to move a bar magnet through a wire coil and measure the resulting electric current through the wire. ... Lenz's law tells us that the current induced will create a magnetic field that will counter this increase. Thus, the magnetic field created by the induced current must be ...

Faraday's experiment showing induction between coils of wire: The liquid battery (right) provides a current which flows through the small coil (A), creating a magnetic field.When the coils are stationary, no current is induced. But when the small coil is moved in or out of the large coil (B), the magnetic flux through the large coil changes, inducing a current which is detected by the ...

Faraday's experiment showing induction between coils of wire: The liquid battery (right) provides a current that flows through the small coil (A), creating a magnetic field.When the coils are stationary, no current is induced. But when the small coil is moved in or out of the large coil (B), the magnetic flux through the large coil changes, inducing a current which is detected by the ...

However, a current is induced in the loop when a relative motion exists between the bar magnet and the loop. In particular, the galvanometer deflects in one direction as the magnet approaches the loop, and the opposite direction as it moves away. Faraday's experiment demonstrates that an electric current is induced in the loop by

induced current in the moving conductor is such that the direction of the magnetic force on the conductor is opposite in direction to its motion (e.g. slide-wire generator). The induced current tries to preserve the "status quo" by opposing motion or a change of flux. B induced downward opposing the change in flux (d Φ/dt).

Faraday's Experiment: Relationship Between Induced EMF and Flux. In the first experiment, he proved that when the strength of the magnetic field is varied, only then current is induced. An ammeter was connected to a loop of wire; the ammeter deflected when a magnet was moved towards the wire. In the second experiment, he proved that passing a ...

ects indicating an induced current in the loop produced by an induced emf (Figure 1b). From these observations, Faraday concluded that there exists a relationship between the induced current/emf and the changing magnetic eld. The results of his experiments are now referred to as Faraday's Law of Induction. In general, Faraday's Law states ...

The famous experiment performed by Michael Faraday lays the groundwork for Faraday's law of induction and conveys the key point that shows the effect of flux changes on the electromotive force and consequent electric current induced. The experiment itself is also quite straightforward, and you can even replicate it for yourself: Faraday wrapped ...

Experiment 1a: Induced Force on Current in Wire. Experiment 1a setup. Use the adjustable silver screw at the center of the magnet attachment to attach the magnet-screw system to the vertical bar of the stand. The copper wire should be suspended in between the magnets by screwing its bar onto the top of the upper bar of the stand.

Play with a bar magnet and coils to learn about Faraday's law. Move a bar magnet near one or two coils to make a light bulb glow. View the magnetic field lines. A meter shows the direction and magnitude of the current. View the magnetic field lines or use a meter to show the direction and magnitude of the current. You can also play with electromagnets, generators and transformers!