Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

The People Power Revolution, Philippines 1986

- Mark John Sanchez

For a moment, everything seemed possible. From February 22 to 25, 1986, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to protest President Ferdinand Marcos and his claim that he had won re-election over Corazon Aquino.

Soon, Marcos and his family were forced to abdicate power and leave the Philippines . Many were optimistic that the Philippines, finally rid of the dictator, would adopt policies to address the economic and social inequalities that had only increased under Marcos’s twenty-year rule. This People Power Revolution surprised and inspired anti-authoritarian activists around the world.

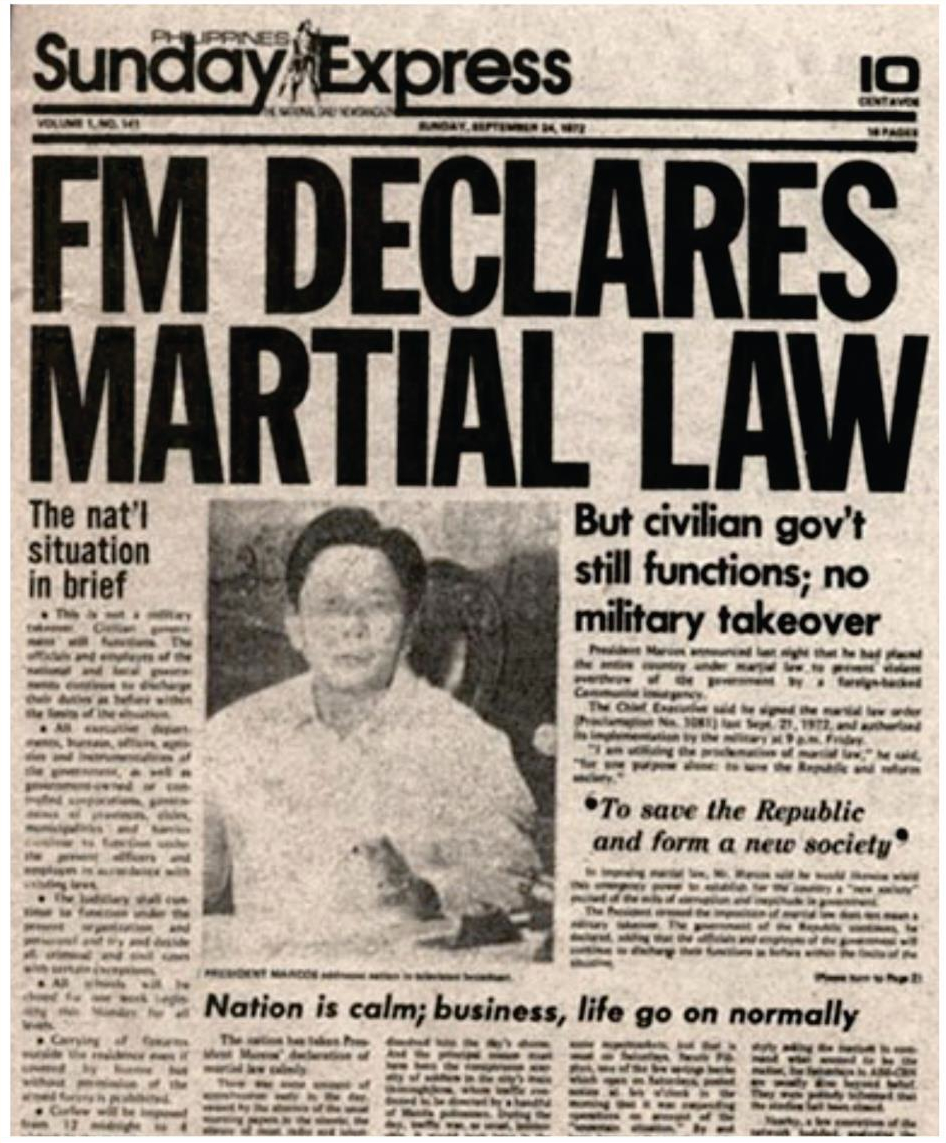

Ferdinand Marcos had been president of the Philippines since 1965. After declaring martial law in 1972, he suspended and eventually rewrote the Philippine constitution, curtailed civil liberties, and concentrated power in the executive branch and among his closest allies. Marcos had tens of thousands of opponents arrested and thousands tortured, killed, or disappeared.

The Sunday Express headline from September 24, 1972 shortly after Marcos declared martial law.

For two decades, Filipinos lived under authoritarian rule while Marcos and his allies enriched themselves through ownership of Philippine press and industry outlets and through the siphoning of funds from U.S., World Bank , and International Monetary Fund loans.

The People Power movement had been building since well before Marcos’s declaration of martial law. Committed activists who organized underground in the Philippines, in exile, and in the diaspora worked tirelessly to broadcast news of the Marcoses’ human rights violations and ill-gotten wealth globally.

For many years, however, much of the world—the U.S. government in particular—was perfectly willing to overlook the corruption of the Marcoses in exchange for an anti-Communist bulwark in Southeast Asia.

By the mid-1980s, however, foreign policy calculations had shifted against Marcos in crucial ways.

Senator Benigno Aquino in an interview with Pat Robertson before his assassination in 1983.

The August 1983 assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was seen by many around the world as a particularly brazen act of political retribution. Furthermore, rumors about Marcos’s health (he was suffering from lupus and regularly undergoing dialysis at the time) led many of his allies in the Philippines and beyond to begin speculating about the dictator’s successors.

When Ferdinand Marcos boldly called for a “snap election” in a 1985 interview with David Brinkley, Marcos’s opponents weighed whether this was an opportunity or a trap. Many times before, Marcos had tipped the electoral balances in his favor, through a rewriting of laws, outright violence, and other forms of manipulation and intimidation.

Much of the Philippine Left decided to boycott the election, fearful that participation would only serve to further legitimize the regime. The remainder of the opposition movement eventually coalesced around the widow of Senator Aquino, Corazon “Cory” Aquino.

Just as many feared, Marcos claimed victory in the election. This time, though, Filipinos refused to accept this lie. On February 22, citizens took to the streets on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Cardinal Jaime Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, called upon Filipinos to support the peaceful protests.

Cardinal Jaime Sin pictured in 1988.

Marcos ordered the military to repress the mass action. However, a faction of military officers refused to clamp down on the protestors and chose instead to defect. This group included soldiers who had grown frustrated with corruption in the military and the Marcos regime and had earlier formed the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM).

When Marcos ordered the military to arrest detractors, Cardinal Sin called upon the people to shield them. The Catholic radio organ, Radio Veritas , became a major control center for protest communications during the People Power movement.

Close Marcos ally President Ronald Reagan eventually sent word through Senator Paul Laxalt that it was time to “cut, and cut cleanly,” signaling that Marcos no longer had the backing of his most powerful ally. On the evening of February 25, the U.S. government facilitated Marcos’s escape to Hawaii, where he would remain until his death in 1989.

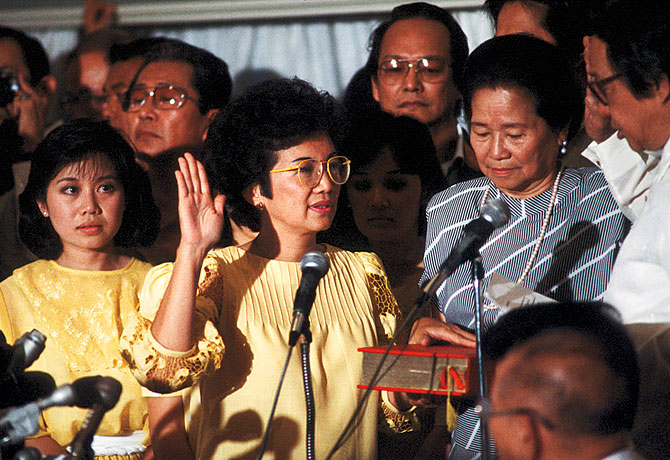

Later that same night, protestors stormed Malacañang Palace, exposing the opulent wealth that the Marcos family had amassed during their time in power. As Corazon Aquino was sworn in as President, Filipinos were hailed around the world as an example of peaceful revolution and the restoration of democracy.

Corazon Aquino was inaugurated as the 11th president of the Philippines on February 25, 1986 at Sampaguita Hall.

The road ahead would not be so simple, however. In the years since 1986, the legacy of the People Power Revolution has remained uncertain. Aquino faced several coup attempts during her time in power, many of them led by the very same RAM that had helped facilitate her rise to power.

The agricultural and economic reform that many Filipinos hoped for in a post-Marcos world did not come. Peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines dissolved and leftists continued to be maligned, attacked, and hunted.

Many Filipinos expressed nostalgia for the very dictator that had been overthrown. And there have been ongoing projects of historical revisionism in the Philippines that sanitized the Marcos years.

The Marcos family have returned to the Philippines and to positions of political prominence: Ferdinand Marcos’s widow Imelda became a congresswoman and his daughter Imee a governor. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the dictator’s son and evident successor to his father’s legacy, ran for vice president in 2016 and finished a close second. Bongbong refused to concede and, to this day, continues his legal challenges to the election.

President Rodrigo Duterte talks to Imee Marcos at a wedding ceremony in Manila, September, 2016.

The most concerning outcome of the 2016 Philippine elections, however, was the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president. A close ally of the Marcoses, Duterte has drawn upon Marcos’s script for authoritarian power. He has arrested prominent opponents, curtailed civil liberties, and claimed that discipline is what is most needed for the Philippine nation.

Most infamously, Duterte launched a campaign that has resulted in tens of thousands of extrajudicial murders committed by police and military forces.

The People Power Movement offers several lessons. We can see the courageous solidarities and coalitions that might mobilize against authoritarian restrictions on civil liberties. But we must also look at the importance of finding ways to build anew and address the grievances and injustices that have made such authoritarians so popular in the first place.

The EDSA protests in 1986 were a remarkable moment in Philippine history, a moment filled with the sense of unlimited hope and possibility. And for those with democratic dreams, it provides both a lesson and a warning for the battles ahead.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

People Power as Immanent Collectivity: Re-Imagining the Miracle of the 1986 EDSA Revolution as Divine Justice

2009, Kritika Kultura

Related papers

ARI Working Paper Series, 2010

Conjunctures and Continuities in Southeast Asia, edited by Narayanan Ganesan, Singapore: ISEAS, in press, 2013

The non-violent removal of Ferdinand Marcos in February 1986 through a mass uprising that had started in 1983 was a landmark event both in the Philippines and internationally. It introduced the term ‘people power’ into academic and journalistic discourse and was used as a model for subsequent civil disobedience movements in Asia and the Soviet bloc. It raises many questions regarding the relationship between civil resistance and other forms of power, and the diVerence between short-term and long-term success. Analysis of non-violent resistance in the Philippines is still incomplete. This chapter attempts to fill this gap by offering reflections on the use of non-violent methods in the Philippine context. The first section offers a historical overview of the uneven democratization process from the early 1970s to the flawed election of 2004. The second section, which is in several parts, addresses questions relating to the role of civil resistance in political change. It considers the reasons for the adoption of non-violent strategies, and the ways in which the coexistence of armed struggles in the Philippines influenced the adoption and effectiveness of non-violent methods. It shows how particular circumstances, especially the regime’s shameless electoral fraud, contributed to the movement’s success. It looks briefly at the role of international power balances generally and the US in particular. Various criteria are suggested for the evaluation of the success and failure of the civil resistance movement during the Marcos and immediate post- Marcos years. The concluding section draws out the links between the practice of civil resistance and democratization, and suggests some lessons which can be learnt from the Philippine example. In particular the conclusion asks what post- authoritarian governance in the Philippines since 1986 shows about a possible connection between the practice of civil resistance and liberal outcomes.

Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 2016

Opinion on the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, 2021

This year marks the 35th anniversary of the momentous 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution. The four-day uprising, which took place from February 22 to 25, will be remembered as the "bloodless" revolution, which brought an end to a government denoted by human rights atrocities, thievery, and tyranny. The People Power Revolution, through the eyes of millions of Filipinos, was a social upheaval that sought to overthrow an authoritarian regime through the collective effort of a democratic nation. This historic event should be remembered by every Filipino citizen, regardless of their gender or age, and should serve as our weapon to eliminate any possibility of another dictatorial, and inhumane ruling of an oppressive government.

Massive peaceful demonstrations ended the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines twenty years ago. The “people power” uprising wascalled a democratic revolution and inspired hopes that it would lead to the consolidationof democracy in the Philippines. When popular uprisings were later used to remove orthreaten other leaders, people power was criticized as an assault on democraticinstitutions and was interpreted as a sign of the political immaturity of Filipinos. Theliterature on people power is presently marked by disagreement as to whether all popularuprisings should be considered part of the people power tradition. The debate isgrounded on the belief that people power was a democratic revolution; other uprisings are judged on how closely they resemble events surrounding Marcos’ ouster from office.This disagreement has become unproductive and has prevented Filipinos from askingquestions about the causes of these uprisings or the failure of democratic consolidation.This Article departs from conventional thought and develops two alternative theories of people power in the Philippines. The first holds that people power is an expression of outrage against a particular public official. The second holds that it is a withdrawal of allegiance from the official in favor of another. Neither view insists that people power isor aspires to democratic revolution. These alternative theories hope to resuscitate thestudy of Philippine democracy.

This paper talks about what made the Martial Law and, consequently, the People Power possible but looks at the bigger picture beyond just the personalities involved in the struggle, seeing it as a struggle of the Filipino people.

Between 1983 and 1986, a huge non-violent ‘People Power’ movement arose in the Philippines to overthrow Marcos, the president who ran the country as a brutal dictatorship. The non-violent movement culminated in a four day ‘People Power’ revolution (also known as the EDSA revolution because of the long street on which people gathered, Epifanio de los Santos Avenue) that, by 25 February 1986, had toppled Marcos. This essay critically examines the non-violent movement during the period 1983-1986. It proceeds under seven headings that consider first, the issues that led to dissent among the people; second, the sparks that transformed this dissent into public protest; third, the leaders of the non-violent movement; fourth, the training in non-violence that was given during this period; fifth, the non-violent strategy and tactics that were employed during the movement; sixth, the international reaction to the movement (the domestic reaction is integrated into many different parts of the essay); and seventh, an evaluation of the movement’s success.

Social Justice Research, 2011

Ana Garduño Ortega, Ekaterina Álvarez Romero y Silvia Rodríguez Molina (eds.), El México antiguo. Colección del Museo Amparo, 2021

G. Moisa, A. Chiriac (Coord.), 150 de ani de muzeografie orădeană, Oradea, 2023

Tomás de Aquino, O ente e a essência. Edição Bilíngue. Tradução e Introdução: Carlos Eduardo de Oliveira. São Paulo: Ideias e Letras., 2024

Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, 2024

Archipel, 2021

LAZ İSMAİL''İN KURTULUŞ SAVAŞI KAHRAMANLIKLARI

Organicom, 2013

Scientific Notes of Ostroh Academy National University, "Economics" Series, 2018

Fruits, 2006

Experimental and clinical cardiology, 2011

Erzincan Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi, 2019

Langmuir, 2022

Plant Physiology, 1994

Microbes and Infection, 2018

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Sulu’s exit shakes up Bangsamoro: 5 scenarios for the 2025 polls

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

EDSA@30: An Unfinished Revolution

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Text and Photos by DAVINCI S. MARU

THIRTY years after the EDSA People Power revolt of 1986, protest marches linger. The protesters hurling often sharp and bitter critique of the myriad reforms that many had expected would follow the fall of the Marcos regime, and the peaceful transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

But EDSA was all of so many things to many people, an inchoate bundle of hopes and dreams not quite easy to fulfill. The expectations were so rich and enormous that not any four-day revolt by any number of street marches could deliver all at once — not just rights restored but also lives improved, and not just repression quashed but also good governance served on a silver platter.

And so, three decades hence, the marches continue.

Discover more from PCIJ.org

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The EDSA protests in 1986 were a remarkable moment in Philippine history, a moment filled with the sense of unlimited hope and possibility. And for those with democratic dreams, it provides both a lesson and a warning for the battles ahead.

EDSA People Power Revolution. The Philippines was praised worldwide in 1986, when the so-called bloodless revolution erupted, called EDSA People Power’s Revolution. February 25, 1986 marked a significant national event that has been engraved in the hearts and minds of every Filipino.

The People Power Revolution, also known as the EDSA Revolution [a] or the February Revolution, [4] [5] [6] [7] were a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines, mostly in Metro Manila, from February 22 to 25, 1986. There was a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud.

During those momentous four days of February 1986, millions of Filipinos, along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Metro Manila, and in cities all over the country, showed exemplary courage and stood against, and peacefully overthrew, the dictatorial regime of President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

the EDSA People Power narrative displaced the stories of his parents and their comrades, or how popular Philippine histories downplayed the role of leftist movements in the anti-Marcos struggle.

The people acted as a collectivity, with its own collective power, opposing the military. This non-aggressive collective power was rooted in a distinctive Filipino culture and religiosity that hailed the EDSA Revolution as a miracle of divine justice.

Edsa Revolution. The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution made a very significant mark in the Philippine history. It was a four-day series of a peaceful rally against the Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. This rally brought down Marcos from Malacanang and was then by replaced by Corazon Aquino.

“Citizens, do you want a revolution without a revolution?” This stirring provocation was delivered by the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre before the National Convention in 1792.

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution was a successful social movement in the Philippines that overthrew the regime of President Ferdinand E. Marcos who had oppressively been in power for 20 years.

THIRTY years after the EDSA People Power revolt of 1986, protest marches linger. The protesters hurling often sharp and bitter critique of the myriad reforms that many had expected would follow the fall of the Marcos regime, and the peaceful transition from authoritarianism to democracy.