- Search Grant Programs

- Application Review Process

- Manage Your Award

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH International Opportunities

- Workshops, Resources, & Tools

- Search All Past Awards

- Divisions and Offices

- Professional Development

- Sign Up to Be a Panelist

- Equity Action Plan

- Emergency and Disaster Relief

- States and Jurisdictions

- Featured NEH-Funded Projects

- Humanities Magazine

- Information for Native and Indigenous Communities

- Information for Pacific Islanders

- Search Our Work

- American Tapestry

- International Engagement

- Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

- Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

- Pacific Islands Cultural Initiative

- United We Stand: Connecting Through Culture

- A More Perfect Union

- NEH Leadership

- Open Government

- Contact NEH

- Press Releases

- NEH in the News

The Painful Legacy of Human Experimentation

Research funded by a 1995 neh grant to wellesley college’s susan reverby became the basis for long-term scholarly engagement with the notorious “tuskegee” syphilis study, and lead to the discovery of a disturbing chapter in the history of human experimentation in guatemala..

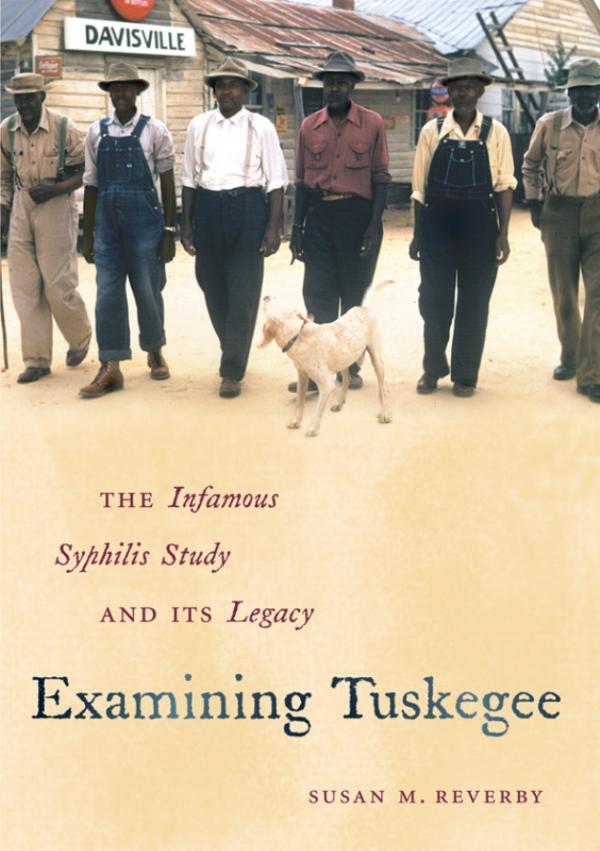

Susan M. Reverby's Examining Tuskegee (UNC Press 2009) has won multiple awards, including the 2011 James F. Sulzby Award from the Alabama Historical Association, and the 2010 Arthur J. Viseltear Award from the American Public Health Association.

Credit: Copyright © 2011 by the University of North Carolina Press.

An NEH grant in 1995 helped Susan M. Reverby of Wellesley College conduct her award-winning research on the infamous "Tuskegee" study.

Credit: Wellesley College

Before 2010, Susan Reverby was perhaps best known for her work investigating the notorious 40-year study of “untreated syphilis in the male Negro,” during which members of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) observed (but did not attempt to treat) the effects of late-stage syphilis in over 400 African American men living around the town of Tuskegee in Macon County, Georgia. Reverby’s research into those experiments, commonly known as the “Tuskegee” study, has already spawned two widely acclaimed books: Tuskegee’s Truths (ed. 2000, UNC Press) and Examining Tuskegee (2009, UNC Press).

And it was while combing through the archives of one of the study’s chief practitioners, Dr. John Cutler of the PHS, that Reverby, an historian of American women, medicine, and nursing at Wellesley College, discovered evidence of a disturbing offshoot of PHS syphilis experimentation, this time in Guatemala. The experiments, conducted from 1946 to 1948 on men and women in Guatemalan army barracks, prisons, and asylums, involved more extreme practices than those associated with the Tuskegee study, including deliberate, painful methods for infecting subjects with syphilis. (Despite popular claims to the contrary, “Tuskegee study” scientists did not - and as Reverby argues, likely could not – surreptitiously infect their American subjects with the sexually transmitted disease.)

Alarmed by the shocking nature of her discovery, Reverby alerted contacts at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, where the late David Sencer, then the director of the CDC, took her findings seriously and quickly commissioned a CDC study of the same archival material that confirmed her research. Reverby’s report on the syphilis experiments in Guatemala, which appeared in the Journal of Policy History in January 2011, includes an addendum about the serious investigative measures taken by the U.S. in the wake of her discovery. On September 16, 2011, the President’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues published a 220-page report on the history and implications of the PHS experiments, and the Commission has used the case as a starting point for further conversation about the ethics of human medical experimentation.

Considering the major influence her research has had, it is difficult to believe that Reverby’s initial proposal to publish her work fell flat. Reverby had intended that the research she conducted in the 1990s on the Tuskegee study, funded in part by a $30,000 NEH grant, would form the heart of a book project on nurse Eunice Rivers Laurie, a controversial figure in the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. Questions surrounding the role of Rivers, a nurse who worked with PHS doctors and administrators over the entire 40-year course of the study, have long fascinated the scholars and the public. But at a fateful meeting in a coffee shop New York City, a disappointed Reverby listened as a literary agent told her that her proposal could not sustain a book-length treatment. “It was a terrible moment,” Reverby said.

Reverby soon found a home for her research on Nurse Rivers in a volume she edited that brought together archival documents and scholarly articles dealing with multiple aspects of the history and reception of the Tuskegee study ( Tuskegee’s Truths , ed. 2000). In 2009, she published Examining Tuskegee , a penetrating look into the historical circumstances of the study, and a sober exploration of the complicated public legacy of “Tuskegee” in America. The book earned widespread praise and won multiple awards, including the 2011 James F. Sulzby Award from the Alabama Historical Association, the 2010 Arthur J. Viseltear Award from the American Public Health Association, and the 2010 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award of the Phi Beta Kappa Society.

Reverby plans to explore further the ways that the stories of public health scandals are told in a future monograph, provisionally titled “Escaping Melodrama.” This latest addition to her long-term and influential research into the history of human experimentation is further proof that a modest investment by the NEH can pay dividends for years to come. Reflecting on the long path of her research on the Tuskegee study and its aftermath, Reverby expressed gratitude for the role that her NEH grant played: “At a small liberal arts college, the workload and emphasis on teaching and service can be so intense, so it’s very important to find funding to make research sabbaticals viable.”

Funding information

Scholar Susan Reverby was awarded a $30,000 NEH fellowship in 1995 to research the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment for a book on nurse Eunice Rivers.

Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered

Shocking as it may seem, U.S. government doctors once thought it was fine to experiment on disabled people and prison inmates. Such experiments included giving hepatitis to mental patients in Connecticut, squirting a pandemic flu virus up the noses of prisoners in Maryland, and injecting cancer cells into chronically ill people at a New York hospital.

Much of this horrific history is 40 to 80 years old, but it is the backdrop for a meeting in Washington this week by a presidential bioethics commission. The meeting was triggered by the government's apology last fall for federal doctors infecting prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis 65 years ago.

U.S. officials also acknowledged there had been dozens of similar experiments in the United States — studies that often involved making healthy people sick.

An exhaustive review by The Associated Press of medical journal reports and decades-old press clippings found more than 40 such studies. At best, these were a search for lifesaving treatments; at worst, some amounted to curiosity-satisfying experiments that hurt people but provided no useful results.

Inevitably, they will be compared to the well-known Tuskegee syphilis study. In that episode, U.S. health officials tracked 600 black men in Alabama who already had syphilis but didn't give them adequate treatment even after penicillin became available.

These studies were worse in at least one respect — they violated the concept of "first do no harm," a fundamental medical principle that stretches back centuries.

"When you give somebody a disease — even by the standards of their time — you really cross the key ethical norm of the profession," said Arthur Caplan, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics.

Attitude similar to Nazi experiments Some of these studies, mostly from the 1940s to the '60s, apparently were never covered by news media. Others were reported at the time, but the focus was on the promise of enduring new cures, while glossing over how test subjects were treated.

Attitudes about medical research were different then. Infectious diseases killed many more people years ago, and doctors worked urgently to invent and test cures. Many prominent researchers felt it was legitimate to experiment on people who did not have full rights in society — people like prisoners, mental patients, poor blacks. It was an attitude in some ways similar to that of Nazi doctors experimenting on Jews.

"There was definitely a sense — that we don't have today — that sacrifice for the nation was important," said Laura Stark, a Wesleyan University assistant professor of science in society, who is writing a book about past federal medical experiments.

The AP review of past research found:

- A federally funded study begun in 1942 injected experimental flu vaccine in male patients at a state insane asylum in Ypsilanti, Mich., then exposed them to flu several months later. It was co-authored by Dr. Jonas Salk, who a decade later would become famous as inventor of the polio vaccine.

Some of the men weren't able to describe their symptoms, raising serious questions about how well they understood what was being done to them. One newspaper account mentioned the test subjects were "senile and debilitated." Then it quickly moved on to the promising results.

- In federally funded studies in the 1940s, noted researcher Dr. W. Paul Havens Jr. exposed men to hepatitis in a series of experiments, including one using patients from mental institutions in Middletown and Norwich, Conn. Havens, a World Health Organization expert on viral diseases, was one of the first scientists to differentiate types of hepatitis and their causes.

A search of various news archives found no mention of the mental patients study, which made eight healthy men ill but broke no new ground in understanding the disease.

- Researchers in the mid-1940s studied the transmission of a deadly stomach bug by having young men swallow unfiltered stool suspension. The study was conducted at the New York State Vocational Institution, a reformatory prison in West Coxsackie. The point was to see how well the disease spread that way as compared to spraying the germs and having test subjects breathe it. Swallowing it was a more effective way to spread the disease, the researchers concluded. The study doesn't explain if the men were rewarded for this awful task.

- A University of Minnesota study in the late 1940s injected 11 public service employee volunteers with malaria, then starved them for five days. Some were also subjected to hard labor, and those men lost an average of 14 pounds. They were treated for malarial fevers with quinine sulfate. One of the authors was Ancel Keys, a noted dietary scientist who developed K-rations for the military and the Mediterranean diet for the public. But a search of various news archives found no mention of the study.

- For a study in 1957, when the Asian flu pandemic was spreading, federal researchers sprayed the virus in the noses of 23 inmates at Patuxent prison in Jessup, Md., to compare their reactions to those of 32 virus-exposed inmates who had been given a new vaccine.

- Government researchers in the 1950s tried to infect about two dozen volunteering prison inmates with gonorrhea using two different methods in an experiment at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The bacteria was pumped directly into the urinary tract through the penis, according to their paper.

The men quickly developed the disease, but the researchers noted this method wasn't comparable to how men normally got infected — by having sex with an infected partner. The men were later treated with antibiotics. The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, but there was no mention of it in various news archives.

Though people in the studies were usually described as volunteers, historians and ethicists have questioned how well these people understood what was to be done to them and why, or whether they were coerced.

Victims for science Prisoners have long been victimized for the sake of science. In 1915, the U.S. government's Dr. Joseph Goldberger — today remembered as a public health hero — recruited Mississippi inmates to go on special rations to prove his theory that the painful illness pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency. (The men were offered pardons for their participation.)

But studies using prisoners were uncommon in the first few decades of the 20th century, and usually performed by researchers considered eccentric even by the standards of the day. One was Dr. L.L. Stanley, resident physician at San Quentin prison in California, who around 1920 attempted to treat older, "devitalized men" by implanting in them testicles from livestock and from recently executed convicts.

Newspapers wrote about Stanley's experiments, but the lack of outrage is striking.

"Enter San Quentin penitentiary in the role of the Fountain of Youth — an institution where the years are made to roll back for men of failing mentality and vitality and where the spring is restored to the step, wit to the brain, vigor to the muscles and ambition to the spirit. All this has been done, is being done ... by a surgeon with a scalpel," began one rosy report published in November 1919 in The Washington Post.

Around the time of World War II, prisoners were enlisted to help the war effort by taking part in studies that could help the troops. For example, a series of malaria studies at Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois and two other prisons was designed to test antimalarial drugs that could help soldiers fighting in the Pacific.

It was at about this time that prosecution of Nazi doctors in 1947 led to the "Nuremberg Code," a set of international rules to protect human test subjects. Many U.S. doctors essentially ignored them, arguing that they applied to Nazi atrocities — not to American medicine.

The late 1940s and 1950s saw huge growth in the U.S. pharmaceutical and health care industries, accompanied by a boom in prisoner experiments funded by both the government and corporations. By the 1960s, at least half the states allowed prisoners to be used as medical guinea pigs.

But two studies in the 1960s proved to be turning points in the public's attitude toward the way test subjects were treated.

The first came to light in 1963. Researchers injected cancer cells into 19 old and debilitated patients at a Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the New York borough of Brooklyn to see if their bodies would reject them.

The hospital director said the patients were not told they were being injected with cancer cells because there was no need — the cells were deemed harmless. But the experiment upset a lawyer named William Hyman who sat on the hospital's board of directors. The state investigated, and the hospital ultimately said any such experiments would require the patient's written consent.

At nearby Staten Island, from 1963 to 1966, a controversial medical study was conducted at the Willowbrook State School for children with mental retardation. The children were intentionally given hepatitis orally and by injection to see if they could then be cured with gamma globulin.

Those two studies — along with the Tuskegee experiment revealed in 1972 — proved to be a "holy trinity" that sparked extensive and critical media coverage and public disgust, said Susan Reverby, the Wellesley College historian who first discovered records of the syphilis study in Guatemala.

'My back is on fire!' By the early 1970s, even experiments involving prisoners were considered scandalous. In widely covered congressional hearings in 1973, pharmaceutical industry officials acknowledged they were using prisoners for testing because they were cheaper than chimpanzees.

Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia made extensive use of inmates for medical experiments. Some of the victims are still around to talk about it. Edward "Yusef" Anthony, featured in a book about the studies, says he agreed to have a layer of skin peeled off his back, which was coated with searing chemicals to test a drug. He did that for money to buy cigarettes in prison.

"I said 'Oh my God, my back is on fire! Take this ... off me!'" Anthony said in an interview with The Associated Press, as he recalled the beginning of weeks of intense itching and agonizing pain.

The government responded with reforms. Among them: The U.S. Bureau of Prisons in the mid-1970s effectively excluded all research by drug companies and other outside agencies within federal prisons.

As the supply of prisoners and mental patients dried up, researchers looked to other countries.

It made sense. Clinical trials could be done more cheaply and with fewer rules. And it was easy to find patients who were taking no medication, a factor that can complicate tests of other drugs.

Additional sets of ethical guidelines have been enacted, and few believe that another Guatemala study could happen today. "It's not that we're out infecting anybody with things," Caplan said.

Still, in the last 15 years, two international studies sparked outrage.

One was likened to Tuskegee. U.S.-funded doctors failed to give the AIDS drug AZT to all the HIV-infected pregnant women in a study in Uganda even though it would have protected their newborns. U.S. health officials argued the study would answer questions about AZT's use in the developing world.

The other study, by Pfizer Inc., gave an antibiotic named Trovan to children with meningitis in Nigeria, although there were doubts about its effectiveness for that disease. Critics blamed the experiment for the deaths of 11 children and the disabling of scores of others. Pfizer settled a lawsuit with Nigerian officials for $75 million but admitted no wrongdoing.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' inspector general reported that between 40 and 65 percent of clinical studies of federally regulated medical products were done in other countries in 2008, and that proportion probably has grown. The report also noted that U.S. regulators inspected fewer than 1 percent of foreign clinical trial sites.

Monitoring research is complicated, and rules that are too rigid could slow new drug development. But it's often hard to get information on international trials, sometimes because of missing records and a paucity of audits, said Dr. Kevin Schulman, a Duke University professor of medicine who has written on the ethics of international studies.

Syphilis study These issues were still being debated when, last October, the Guatemala study came to light.

In the 1946-48 study, American scientists infected prisoners and patients in a mental hospital in Guatemala with syphilis, apparently to test whether penicillin could prevent some sexually transmitted disease. The study came up with no useful information and was hidden for decades.

Story: U.S. apologizes for Guatemala syphilis experiments

The Guatemala study nauseated ethicists on multiple levels. Beyond infecting patients with a terrible illness, it was clear that people in the study did not understand what was being done to them or were not able to give their consent. Indeed, though it happened at a time when scientists were quick to publish research that showed frank disinterest in the rights of study participants, this study was buried in file drawers.

"It was unusually unethical, even at the time," said Stark, the Wesleyan researcher.

"When the president was briefed on the details of the Guatemalan episode, one of his first questions was whether this sort of thing could still happen today," said Rick Weiss, a spokesman for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

That it occurred overseas was an opening for the Obama administration to have the bioethics panel seek a new evaluation of international medical studies. The president also asked the Institute of Medicine to further probe the Guatemala study, but the IOM relinquished the assignment in November, after reporting its own conflict of interest: In the 1940s, five members of one of the IOM's sister organizations played prominent roles in federal syphilis research and had links to the Guatemala study.

So the bioethics commission gets both tasks. To focus on federally funded international studies, the commission has formed an international panel of about a dozen experts in ethics, science and clinical research. Regarding the look at the Guatemala study, the commission has hired 15 staff investigators and is working with additional historians and other consulting experts.

The panel is to send a report to Obama by September. Any further steps would be up to the administration.

Some experts say that given such a tight deadline, it would be a surprise if the commission produced substantive new information about past studies. "They face a really tough challenge," Caplan said.

- Philadelphia

A brief history of the Holmesburg Prison experiments

A timeline of the medical experiments at Holmesburg prison and the after effects on the inmates who participated.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/CJ2VAARQP5EB7KQSZP3HWWVOIU.jpg)

The Holmesburg Prison experiments ended 50 years ago , but their impact remains with the victims and their families. A brief history of the experiments:

1951: Albert Kligman, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist, begins experiments on people incarcerated at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia for such companies as Johnson & Johnson and Dow Chemical, as well as the U.S. Army, which commissioned Kligman to test hallucinogenic and psychotropic drugs. The Holmesburg testing program lasted 23 years.

1967: Kligman patents Retin-A, an acne medication. He and the University of Pennsylvania license it to Johnson & Johnson, which began selling it in 1971. A decade later, after discovering Retin-A’s anti-wrinkle use, Kligman is issued a new patent, but Penn argues that the right to license the patent belongs to the university. In 1989, an acrimonious lawsuit ensues, ending in 1992 with an agreement to share royalties with the medical school.

» READ MORE: Those affected by Holmesburg Prison experiments are still seeking justice, 50 years later

1972: The Associated Press reports on the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male , which began in 1932 and lasted 40 years. The reporting fuels a public outcry and a congressional hearing the following year.

1974: Philadelphia bans medical testing at Holmesburg.

1984: Leodus Jones, father of Adrianne Jones-Alston and founder of Community Assistance for Prisoners in Philadelphia, files a lawsuit seeking damages. He was one of the few incarcerated people to successfully sue, reaching a $40,000 settlement with the City of Philadelphia in 1986. Jones died in 2018.

1995: Holmesburg, which opened in 1896 for those serving short sentences or awaiting trial, closes.

1998: Allen M. Hornblum , who was director of adult literacy for Philadelphia prisons and became aware of the testing program, releases his book, “ Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison ,” which documented the horrors of the medical experiments.

2000: About 300 former Holmesburg study participants sue Kligman, Penn, the City of Philadelphia, Dow Chemical, and Johnson & Johnson for exposing them to “infectious diseases, radioactive isotopes, and psychotic drugs such as LSD without having given informed consent.” A year later, a court rules that the statute of limitations had expired.

2002: City Council holds a hearing on the medical experiments at Holmesburg.

2003: A group known as The Holmesburg Survivors protests outside the College of Physicians when it presents a lifetime achievement award to Kligman. The College of Physicians issues an apology 20 years later, in 2023.

2010: Kligman, 93, dies of a heart attack. He had been a member of Penn’s faculty for over 50 years.

2021: J. Larry Jameson, then the dean of Penn Medicine and now Interim President of the University of Pennsylvania, issues an apology, calling Kligman’s experiments “disrespectful.”

2022: Then-Mayor Jim Kenney follows with an apology from the city. “To the families and loved ones across generations who have been impacted by this deplorable chapter in our city’s history, we are hopeful this formal apology brings you at least a small measure of closure.”

Support PCRM's Saving Animals Saves People Campaign.

Help us raise $100,000 by November 30, 2024.

- For Clinicians

- For Medical Students

- For Scientists

- Our Victories

- Internships

- Annual & Financial Reports

- Barnard Medical Center

Human Experimentation: An Introduction to the Ethical Issues

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

In January 1944, a 17-year-old Navy seaman named Nathan Schnurman volunteered to test protective clothing for the Navy. Following orders, he donned a gas mask and special clothes and was escorted into a 10-foot by 10-foot chamber, which was then locked from the outside. Sulfur mustard and Lewisite, poisonous gasses used in chemical weapons, were released into the chamber and, for one hour each day for five days, the seaman sat in this noxious vapor. On the final day, he became nauseous, his eyes and throat began to burn, and he asked twice to leave the chamber. Both times he was told he needed to remain until the experiment was complete. Ultimately Schnurman collapsed into unconsciousness and went into cardiac arrest. When he awoke, he had painful blisters on most of his body. He was not given any medical treatment and was ordered to never speak about what he experienced under the threat of being tried for treason. For 49 years these experiments were unknown to the public.

The Scandal Unfolds

In 1993, the National Academy of Sciences exposed a series of chemical weapons experiments stretching from 1944 to 1975 which involved 60,000 American GIs. At least 4,000 were used in gas-chamber experiments such as the one described above. In addition, more than 210,000 civilians and GIs were subjected to hundreds of radiation tests from 1945 through 1962.

Testimony delivered to Congress detailed the studies, explaining that “these tests and experiments often involved hazardous substances such as radiation, blister and nerve agents, biological agents, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)....Although some participants suffered immediate acute injuries, and some died, in other cases adverse health problems were not discovered until many years later—often 20 to 30 years or longer.” 1

These examples and others like them—such as the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments (1932-72) and the continued testing of unnecessary (and frequently risky) pharmaceuticals on human volunteers—demonstrate the danger in assuming that adequate measures are in place to ensure ethical behavior in research.

Tuskegee Studies

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service in conjunction with the Tuskegee Institute began the now notorious “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” The study purported to learn more about the treatment of syphilis and to justify treatment programs for African Americans. Six hundred African American men, 399 of whom had syphilis, became participants. They were given free medical exams, free meals, and burial insurance as recompense for their participation and were told they would be treated for “bad blood,” a term in use at the time referring to a number of ailments including syphilis, when, in fact, they did not receive proper treatment and were not informed that the study aimed to document the progression of syphilis without treatment. Penicillin was considered the standard treatment by 1947, but this treatment was never offered to the men. Indeed, the researchers took steps to ensure that participants would not receive proper treatment in order to advance the objectives of the study. Although, the study was originally projected to last only 6 months, it continued for 40 years.

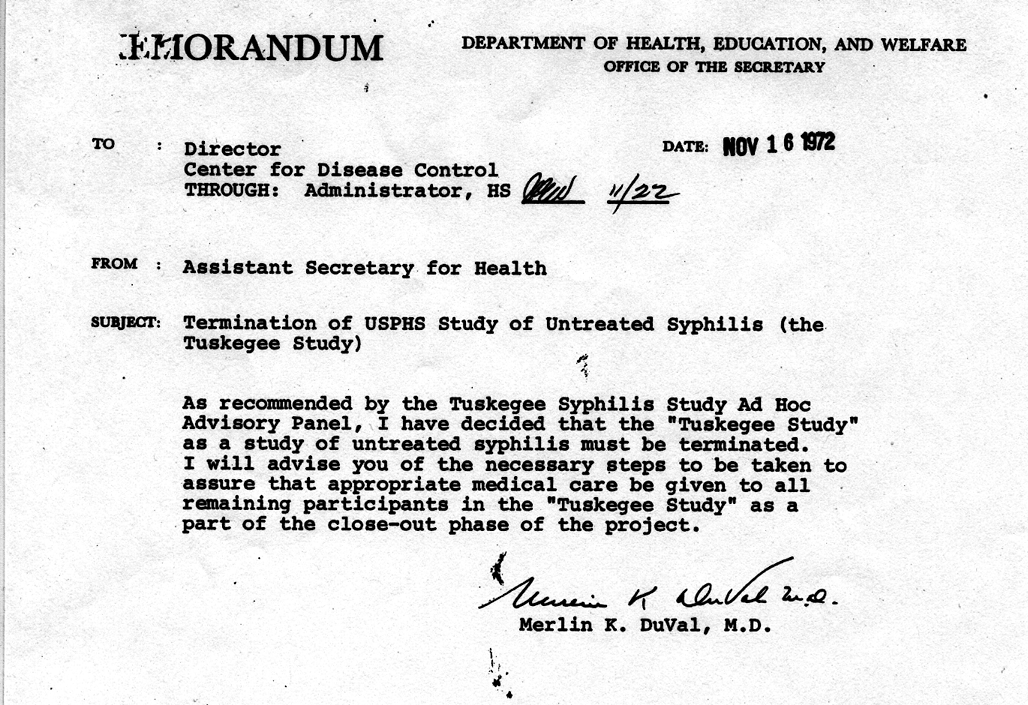

Following a front-page New York Times article denouncing the studies in 1972, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs appointed a committee to investigate the experiment. The committee found the study ethically unjustified and within a month it was ended. The following year, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People won a $9 million class action suit on behalf of the Tuskegee participants. However, it was not until May 16, 1997, when President Clinton addressed the eight surviving Tuskegee participants and others active in keeping the memory of Tuskegee alive, that a formal apology was issued by the government.

While Tuskegee and the discussed U.S. military experiments stand out in their disregard for the well-being of human subjects, more recent questionable research is usually devoid of obvious malevolent intentions. However, when curiosity is not curbed with compassion, the results can be tragic.

Unnecessary Drugs Mean Unnecessary Experiments

A widespread ethical problem, although one that has not yet received much attention, is raised by the development of new pharmaceuticals. All new drugs are tested on human volunteers. There is, of course, no way subjects can be fully apprised of the risks in advance, as that is what the tests purport to determine. This situation is generally considered acceptable, provided volunteers give “informed” consent. Many of the drugs under development today, however, offer little clinical benefit beyond those available from existing treatments. Many are developed simply to create a patentable variation on an existing drug. It is easy to justify asking informed, consenting individuals to risk limited harm in order to develop new drug therapies for a condition from which they are suffering or for which existing treatments are inadequate. The same may not apply when the drug being tested offers no new benefits to the subjects because they are healthy volunteers, or when the drug offers no significant benefits to anyone because it is essentially a copy of an existing drug.

Manufacturers, of course, hope that animal tests will give an indication of how a given drug will affect humans. However, a full 70 to 75 percent of drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration for clinical trials based on promising results in animal tests, ultimately prove unsafe or ineffective for humans. 2 Even limited clinical trials cannot reveal the full range of drug risks. A U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) study reports that of the 198 new drugs which entered the market between 1976 and 1985, 102 (52 percent) caused adverse reactions that premarket tests failed to predict. 3 Even in the brief period between January and August 1997, at least 53 drugs currently on the market were relabeled due to unexpected adverse effects. 4

In the GAO study, no fewer than eight of the drugs in question were benzodiazepines, similar to Valium, Librium, and numerous other sedatives of this class. Two were heterocyclic antidepressants, adding little or nothing to the numerous existing drugs of this type. Several others were variations of cephalosporin antibiotics, antihypertensives, and fertility drugs. These are not needed drugs. The risks taken to develop these drugs by trial participants, and to a certain extent by consumers, were not in the name of science, but in the name of market share.

As physicians, we necessarily have a relationship with the pharmaceutical companies that produce, develop, and market drugs involved in medical treatment. A reflective, perhaps critical posture towards some of the standard practices of these companies—such as the routine development of unnecessary drugs—may help to ensure higher ethical standards in research.

Unnecessary Experimentation on Children

Unnecessary and questionable human experimentation is not limited to pharmaceutical development. In experiments at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a genetically engineered human growth hormone (hGH) is injected into healthy short children. Consent is obtained from parents and affirmed by the children themselves. The children receive 156 injections each year in the hope of becoming taller.

Growth hormone is clearly indicated for hormone-deficient children who would otherwise remain extremely short. Until the early 1980s, they were the only ones eligible to receive it; because it was harvested from human cadavers, supplies were limited. But genetic engineering changed that, and the hormone can now be manufactured in mass quantities. This has led pharmaceutical houses to eye a huge potential market: healthy children who are simply shorter than average.

Short stature, of course, is not a disease. The problems short children face relate only to how others react to their height and their own feelings about it. The hGH injection, on the other hand, poses significant risks, both physical and psychological.

These injections are linked in some studies to a potential for increased cancer risk, 5-8 are painful, and may aggravate, rather than reduce, the stigma of short stature. 9,10 Moreover, while growth rate is increased in the short term, it is unclear that the final net height of the child is significantly increased by the treatment.

The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine worked to halt these experiments and recommended that the biological and psychological effects of hGH treatment be studied in hormone-deficient children who already receive hGH, and that non-pharmacologic interventions to counteract the stigma of short stature also be investigated. Unfortunately, the hGH studies have continued without modification, putting healthy short children at risk.

Use of Placebo in Clinical Research

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, is a serious threat to infants, with dangerous and sometimes fatal complications. Vaccination has nearly wiped out pertussis in the U.S. Uncertainties remain, however, over the relative merits and safety of traditional whole-cell vaccines versus newer, acellular versions, prompting the NIH to propose an experiment testing various vaccines on children.

The controversial part of the 1993 experiment was the inclusion of a placebo group of more than 500 infants who get no protection at all, an estimated 5 percent of whom were expected to develop whooping cough, compared to the 1.4 percent estimated risk for the study group as a whole. Because of these risks, this study would not be permissible in the U.S. The NIH, however, insisted on the inclusion of a placebo control and therefore initiated the study in Italy where there are fewer restrictions on human research trials. Originally, Italian health officials recoiled from these studies on ethical as well as practical grounds, but persistent pressure from the NIH ensured that the study was conducted with the placebo group.

The use of double-blind placebo-controlled studies is the “gold standard” in the research community, usually for good reason. However, when a well-accepted treatment is available, the use of a placebo control group is not always acceptable and is sometimes unethical. 11 In such cases, it is often appropriate to conduct research using the standard treatment as an active control. The pertussis experiments on Italian children were an example of dogmatic adherence to a research protocol which trumped ethical concerns.

Placebos, Ethics, and Poorer Nations

The ethical problems that placebo-controlled trials raise are especially complicated in research conducted in economically disadvantaged countries. Recently, attention has been brought to studies conducted in Africa on preventing the transmission of HIV from mothers to newborns. Standard treatment for HIV-infected pregnant women in the U.S. is a costly regimen of AZT. This treatment can save the life of one in seven infants born to women with AIDS. 12 Sadly, the cost of AZT treatment is well beyond the means of most of the world’s population. This troubling situation has motivated studies to find a cost-effective treatment that can confer at least some benefit in poorer countries where the current standard of care is no treatment at all. A variety of these studies is now underway in which a control group of HIV-positive pregnant women receives no antiretroviral treatment.

Such studies would clearly be unethical in the U.S. where AZT treatment is the standard of care for all HIV-positive mothers. Peter Lurie, M.D., M.P.H., and Sidney Wolfe, M.D., in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine , hold that such use of placebo controls in research trials in poor nations is unethical as well. They contend that, by using placebo control groups, researchers adopt a double standard leading to “an incentive to use as research subjects those with the least access to health care.” 13 Lurie and Wolfe argue that an active control receiving the standard regimen of AZT can and should be compared with promising alternative therapies (such as a reduced dosage of AZT) to develop an effective, affordable treatment for poor countries.

Control Groups and Nutrition

Similar ethical problems are also emerging in nutrition research. In the past, it was ethical for prevention trials in heart disease or other serious conditions to include a control group which received weak nutritional guidelines or no dietary intervention at all. However, that was before diet and lifestyle changes—particularly those using very low fat, vegetarian diets—were shown to reverse existing heart disease, push adult-onset diabetes into remission, significantly lower blood pressure, and reduce the risk of some forms of cancer. Perhaps in the not-too-distant future, such comparison groups will no longer be permissible.

The Ethical Landscape

Ethical issues in human research generally arise in relation to population groups that are vulnerable to abuse. For example, much of the ethically dubious research conducted in poor countries would not occur were the level of medical care not so limited. Similarly, the cruelty of the Tuskegee experiments clearly reflected racial prejudice. The NIH experiments on short children were motivated to counter a fundamentally social problem, the stigma of short stature, with a profitable pharmacologic solution. The unethical military experiments during the Cold War would have been impossible if GIs had had the right to abort assignments or raise complaints. As we address the ethical issues of human experimentation, we often find ourselves traversing complex ethical terrain. Vigilance is most essential when vulnerable populations are involved.

- Frank C. Conahan of the National Security and International Affairs Division of the General Accounting Office, reporting to the Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations.

- Flieger K. Testing drugs in people. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. September 10, 1997.

- U.S. General Accounting Office. FDA Drug Review: Postapproval Risks 1976-85. U.S. General Accounting Office, Washington, D.C., 1990.

- MedWatch, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Labeling changes related to drug safety. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page; http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety.htm . September 10, 1997.

- Arteaga CL, Osborne CK. Growth inhibition of human breast cancer cells in vitro with an antibody against the type I somatomedin receptor. Cancer Res . 1989;49:6237-6241.

- Pollak M, Costantino J, Polychronakos C, et al. Effect of tamoxifen on serum insulin-like growth factor I levels in stage I breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst . 1990;82:1693-1697.

- Stoll BA. Growth hormone and breast cancer. Clin Oncol . 1992;4:4-5.

- Stoll BA. Does extra height justify a higher risk of breast cancer? Ann Oncol . 1992;3:29-30.

- Kusalic M, Fortin C. Growth hormone treatment in hypopituitary dwarfs: longitudinal psychological effects. Canad Psychiatric Asso J . 1975;20:325-331.

- Grew RS, Stabler B, Williams RW, Underwood LE. Facilitating patient understanding in the treatment of growth delay. Clin Pediatr . 1983;22:685-90.

- For a more extensive discussion of the ethical status of placebo-controlled trials see especially: Freedman B, Glass KC, Weijer C. Placebo orthodoxy in clinical research II: ethical, legal and regulatory myths. J Law Med Ethics . 1996;24:252-259.

- Lurie P, Wolfe SM. Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunnodeficiency virus in developing countries. N Engl J Med . 1997:337:12:853.

More on Ethical Science

News Release

Ethical Science News

Main navigation

- Our Articles

- Dr. Joe's Books

- Media and Press

- Our History

- Public Lectures

- Past Newsletters

- Photo Gallery: The McGill OSS Separates 25 Years of Separating Sense from Nonsense

Subscribe to the OSS Weekly Newsletter!

40 years of human experimentation in america: the tuskegee study.

- Add to calendar

- Tweet Widget

Starting in 1932, 600 African American men from Macon County, Alabama were enlisted to partake in a scientific experiment on syphilis. The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” was conducted by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and involved blood tests, x-rays, spinal taps and autopsies of the subjects.

The goal was to “observe the natural history of untreated syphilis” in black populations. But the subjects were unaware of this and were simply told they were receiving treatment for bad blood. Actually, they received no treatment at all. Even after penicillin was discovered as a safe and reliable cure for syphilis, the majority of men did not receive it.

To really understand the heinous nature of the Tuskegee Experiment requires some societal context, a lot of history, and a realization of just how many times government agencies were given a chance to stop this human experimentation but didn’t.

In 1865, the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution formally ended the enslavement of black Americans. But by the early 20 th century, the cultural and medical landscape of the U.S. was still built upon and inundated with racist concepts. Social Darwinism was rising, predicated on the survival of the fittest, and “ scientific racism ” (a pseudoscientific practice of using science to reinforce racial biases) was common. Many white people already thought themselves superior to blacks and science and medicine was all too happy to reinforce this hierarchy.

Before the ending of slavery, scientific racism was used to justify the African slave trade. Scientists argued that African men were uniquely fit for enslavement due to their physical strength and simple minds. They argued that slaves possessed primitive nervous systems, so did not experience pain as white people did. Enslaved African Americans in the South were claimed to suffer from mental illness at rates lower than their free Northern counterparts (thereby proving that enslavement was good for them), and slaves who ran away were said to be suffering from their own mental illness known as drapetomania.

During and after the American Civil War, African Americans were argued to be a different species from white Americans, and mixed-race children were presumed prone to many medical issues. Doctors of the time testified that the emancipation of slaves had caused the “mental, moral and physical deterioration of the black population,” observing that “virtually free of disease as slaves, they were now overwhelmed by it.” Many believed that the African Americans were doomed to extinction, and arguments were made about their physiology being unsuited for the colder climates of America (thus they should be returned to Africa).

Scientific and medical authorities of the late 19 th /early 20 th centuries held extremely harmful pseudoscientific ideas specifically about the sex drives and genitals of African Americans. It was widely believed that, while the brains of African Americans were under-evolved, their genitals were over-developed. Black men were seen to have an intrinsic perversion for white women, and all African Americans were seen as inherently immoral, with insatiable sexual appetites.

This all matters because it was with these understandings of race, sexuality and health that researchers undertook the Tuskegee study. They believed, largely due to their fundamentally flawed scientific understandings of race, that black people were extremely prone to sexually transmitted infections (like syphilis). Low birth rates and high miscarriage rates were universally blamed on STIs.

They also believed that all black people, regardless of their education, background, economic or personal situations, could not be convinced to get treatment for syphilis. Thus, the USPHS could justify the Tuskegee study, calling it a “study in nature” rather than an experiment, meant to simply observe the natural progression of syphilis within a community that wouldn’t seek treatment.

The USPHS set their study in Macon County due to estimates that 35% of its population was infected with syphilis. In 1932, the initial patients between the ages of 25 and 60 were recruited under the guise of receiving free medical care for “bad blood,” a colloquial term encompassing anemia, syphilis, fatigue and other conditions. Told that the treatment would last only six months, they received physical examinations, x-rays, spinal taps, and when they died, autopsies.

Researchers faced a lack of participants due to fears that the physical examinations were actually for the purpose of recruiting them to the military. To assuage these fears, doctors began examining women and children as well. Men diagnosed with syphilis who were of the appropriate age were recruited for the study, while others received proper treatments for their syphilis (at the time these were commonly mercury - or arsenic -containing medicines).

In 1933, researchers decided to continue the study long term. They recruited 200+ control patients who did not have syphilis (simply switching them to the syphilis-positive group if at any time they developed it). They also began giving all patients ineffective medicines ( ointments or capsules with too small doses of neoarsphenamine or mercury) to further their belief that they were being treated.

As time progressed, however, patients began to stop attending their appointments. To greater incentivize them to remain a part of the study, the USPHS hired a nurse named Eunice Rivers to drive them to and from their appointments, provide them with hot meals and deliver their medicines, services especially valuable to subjects during the Great Depression. In an effort to ensure the autopsies of their test subjects, the researchers also began covering patient’s funeral expenses.

Multiple times throughout the experiment researchers actively worked to ensure that their subjects did not receive treatment for syphilis. In 1934 they provided doctors in Macon County with lists of their subjects and asked them not to treat them. In 1940 they did the same with the Alabama Health Department. In 1941 many of the men were drafted and had their syphilis uncovered by the entrance medical exam, so the researchers had the men removed from the army, rather than let their syphilis be treated.

It was in these moments that the Tuskegee study’s true nature became clear. Rather than simply observing and documenting the natural progression of syphilis in the community as had been planned, the researchers intervened: first by telling the participants that they were being treated (a lie), and then again by preventing their participants from seeking treatment that could save their lives. Thus, the original basis for the study--that the people of Macon County would likely not seek treatment and thus could be observed as their syphilis progressed--became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Henderson Act was passed in 1943, requiring tests and treatments for venereal diseases to be publicly funded, and by 1947, penicillin had become the standard treatment for syphilis , prompting the USPHS to open several Rapid Treatment Centers specifically to treat syphilis with penicillin. All the while they were actively preventing 399 men from receiving the same treatments.

By 1952, however, about 30% of the participants had received penicillin anyway, despite the researchers’ best efforts. Regardless, the USPHS argued that their participants wouldn’t seek penicillin or stick to the prescribed treatment plans. They claimed that their participants, all black men, were too “stoic” to visit a doctor. In truth these men thought they were already being treated, so why would they seek out further treatment?

The researchers’ tune changed again as time went on. In 1965, they argued that it was too late to give the subjects penicillin, as their syphilis had progressed too far for the drug to help. While a convenient justification for their continuation of the study, penicillin is (and was) recommended for all stages of syphilis and could have stopped the disease’s progression in the patients.

In 1947 the Nuremberg code was written, and in 1964 the World Health Organization published their Declaration of Helsinki . Both aimed to protect humans from experimentation, but despite this, the Centers for Disease Control (which had taken over from the USPHS in controlling the study) actively decided to continue the study as late as 1969.

It wasn’t until a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, leaked information about the study to the New York Times and the paper published it on the front page on November 16 th , 1972, that the Tuskegee study finally ended. By this time only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. 128 patients had died of syphilis or its complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children had acquired congenital syphilis.

There was mass public outrage, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People launched a class action lawsuit against the USPHS. It settled the suit two years later for 10 million dollars and agreed to pay the medical treatments of all surviving participants and infected family members, the last of whom died in 2009.

Largely in response to the Tuskegee study, Congress passed the National Research Act in 1974, and the Office for Human Research Protections was established within the USPHS. Obtaining informed consent from all study participants became required for all research on humans, with this process overseen by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) within academia and hospitals.

The Tuskegee study has had lasting effects on America . It’s estimated that the life expectancy of black men fell by up to 1.4 years when the study’s details came to light. Many also blame the study for impacting the willingness of black individuals to willingly participate in medical research today.

We know all about evil Nazis who experimented on prisoners. We condemn the scientists in Marvel movies who carry out tests on prisoners of war. But we’d do well to remember that America has also used its own people as lab rats . Yet to this day, no one has been prosecuted for their role in dooming 399 men to syphilis.

Want to comment on this article? View it on our Facebook page!

What to read next

The true story of frankenstein 30 oct 2024.

The Beginnings of Chemical Synthesis 22 Oct 2024

Having Trouble with Faces? There’s a Name for That 18 Oct 2024

We Have a Surplus of Baby Boys 4 Oct 2024

John Dalton’s Eyeball 2 Oct 2024

The Life and Death of a Soviet-Era Search for Longevity 20 Sep 2024

Department and University Information

Office for science and society.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Numerous experiments which were performed on human test subjects in the United States in the past are now considered to have been unethical, because they were performed without the knowledge or informed consent of the test subjects. Such tests have been performed throughout American history, but have become significantly less frequent with the adven…

On September 16, 2011, the President’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues published a 220-page report on the history and implications of the PHS experiments, and the …

Since the late 19th century, numerous human experiments were performed in the United States, which were later characterized as unethical. They were often performed illegally, without the knowledge, consent, or informed consent of the test subjects. Examples have included the deliberate infection of people with deadly or debilitating diseases, exposing people to biological and chemical weapons, human radiation experiments, injecting people with toxic and radioactive chemi…

What makes some human experiments unethical, and what should we do with the ones that have contributed to current medicine?

Such experiments included giving hepatitis to mental patients in Connecticut, squirting a pandemic flu virus up the noses of prisoners in Maryland, and injecting cancer cells …

1995: Holmesburg, which opened in 1896 for those serving short sentences or awaiting trial, closes. 1998: Allen M. Hornblum, who was director of adult literacy for …

While Tuskegee and the discussed U.S. military experiments stand out in their disregard for the well-being of human subjects, more recent questionable research is usually devoid of obvious malevolent intentions. …

Starting in 1932, 600 African American men from Macon County, Alabama were enlisted to partake in a scientific experiment on syphilis. The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” was conducted by …