Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to do a content analysis

What is content analysis?

Why would you use a content analysis, types of content analysis, conceptual content analysis, relational content analysis, reliability and validity, reliability, the advantages and disadvantages of content analysis, a step-by-step guide to conducting a content analysis, step 1: develop your research questions, step 2: choose the content you’ll analyze, step 3: identify your biases, step 4: define the units and categories of coding, step 5: develop a coding scheme, step 6: code the content, step 7: analyze the results, frequently asked questions about content analysis, related articles.

In research, content analysis is the process of analyzing content and its features with the aim of identifying patterns and the presence of words, themes, and concepts within the content. Simply put, content analysis is a research method that aims to present the trends, patterns, concepts, and ideas in content as objective, quantitative or qualitative data , depending on the specific use case.

As such, some of the objectives of content analysis include:

- Simplifying complex, unstructured content.

- Identifying trends, patterns, and relationships in the content.

- Determining the characteristics of the content.

- Identifying the intentions of individuals through the analysis of the content.

- Identifying the implied aspects in the content.

Typically, when doing a content analysis, you’ll gather data not only from written text sources like newspapers, books, journals, and magazines but also from a variety of other oral and visual sources of content like:

- Voice recordings, speeches, and interviews.

- Web content, blogs, and social media content.

- Films, videos, and photographs.

One of content analysis’s distinguishing features is that you'll be able to gather data for research without physically gathering data from participants. In other words, when doing a content analysis, you don't need to interact with people directly.

The process of doing a content analysis usually involves categorizing or coding concepts, words, and themes within the content and analyzing the results. We’ll look at the process in more detail below.

Typically, you’ll use content analysis when you want to:

- Identify the intentions, communication trends, or communication patterns of an individual, a group of people, or even an institution.

- Analyze and describe the behavioral and attitudinal responses of individuals to communications.

- Determine the emotional or psychological state of an individual or a group of people.

- Analyze the international differences in communication content.

- Analyzing audience responses to content.

Keep in mind, though, that these are just some examples of use cases where a content analysis might be appropriate and there are many others.

The key thing to remember is that content analysis will help you quantify the occurrence of specific words, phrases, themes, and concepts in content. Moreover, it can also be used when you want to make qualitative inferences out of the data by analyzing the semantic meanings and interrelationships between words, themes, and concepts.

In general, there are two types of content analysis: conceptual and relational analysis . Although these two types follow largely similar processes, their outcomes differ. As such, each of these types can provide different results, interpretations, and conclusions. With that in mind, let’s now look at these two types of content analysis in more detail.

With conceptual analysis, you’ll determine the existence of certain concepts within the content and identify their frequency. In other words, conceptual analysis involves the number of times a specific concept appears in the content.

Conceptual analysis is typically focused on explicit data, which means you’ll focus your analysis on a specific concept to identify its presence in the content and determine its frequency.

However, when conducting a content analysis, you can also use implicit data. This approach is more involved, complicated, and requires the use of a dictionary, contextual translation rules, or a combination of both.

No matter what type you use, conceptual analysis brings an element of quantitive analysis into a qualitative approach to research.

Relational content analysis takes conceptual analysis a step further. So, while the process starts in the same way by identifying concepts in content, it doesn’t focus on finding the frequency of these concepts, but rather on the relationships between the concepts, the context in which they appear in the content, and their interrelationships.

Before starting with a relational analysis, you’ll first need to decide on which subcategory of relational analysis you’ll use:

- Affect extraction: With this relational content analysis approach, you’ll evaluate concepts based on their emotional attributes. You’ll typically assess these emotions on a rating scale with higher values assigned to positive emotions and lower values to negative ones. In turn, this allows you to capture the emotions of the writer or speaker at the time the content is created. The main difficulty with this approach is that emotions can differ over time and across populations.

- Proximity analysis: With this approach, you’ll identify concepts as in conceptual analysis, but you’ll evaluate the way in which they occur together in the content. In other words, proximity analysis allows you to analyze the relationship between concepts and derive a concept matrix from which you’ll be able to develop meaning. Proximity analysis is typically used when you want to extract facts from the content rather than contextual, emotional, or cultural factors.

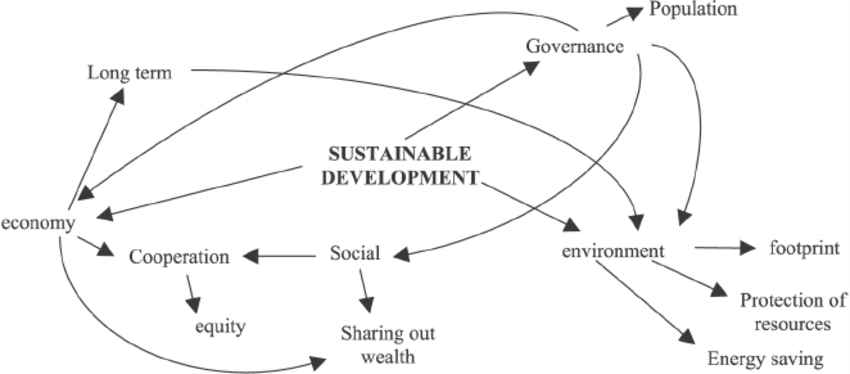

- Cognitive mapping: Finally, cognitive mapping can be used with affect extraction or proximity analysis. It’s a visualization technique that allows you to create a model that represents the overall meaning of content and presents it as a graphic map of the relationships between concepts. As such, it’s also commonly used when analyzing the changes in meanings, definitions, and terms over time.

Now that we’ve seen what content analysis is and looked at the different types of content analysis, it’s important to understand how reliable it is as a research method . We’ll also look at what criteria impact the validity of a content analysis.

There are three criteria that determine the reliability of a content analysis:

- Stability . Stability refers to the tendency of coders to consistently categorize or code the same data in the same way over time.

- Reproducibility . This criterion refers to the tendency of coders to classify categories membership in the same way.

- Accuracy . Accuracy refers to the extent to which the classification of content corresponds to a specific standard.

Keep in mind, though, that because you’ll need to code or categorize the concepts you’ll aim to identify and analyze manually, you’ll never be able to eliminate human error. However, you’ll be able to minimize it.

In turn, three criteria determine the validity of a content analysis:

- Closeness of categories . This is achieved by using multiple classifiers to get an agreed-upon definition for a specific category by using either implicit variables or synonyms. In this way, the category can be broadened to include more relevant data.

- Conclusions . Here, it’s crucial to decide what level of implication will be allowable. In other words, it’s important to consider whether the conclusions are valid based on the data or whether they can be explained using some other phenomena.

- Generalizability of the results of the analysis to a theory . Generalizability comes down to how you determine your categories as mentioned above and how reliable those categories are. In turn, this relies on how accurately the categories are at measuring the concepts or ideas that you’re looking to measure.

Considering everything mentioned above, there are definite advantages and disadvantages when it comes to content analysis:

Let’s now look at the steps you’ll need to follow when doing a content analysis.

The first step will always be to formulate your research questions. This is simply because, without clear and defined research questions, you won’t know what question to answer and, by implication, won’t be able to code your concepts.

Based on your research questions, you’ll then need to decide what content you’ll analyze. Here, you’ll use three factors to find the right content:

- The type of content . Here you’ll need to consider the various types of content you’ll use and their medium like, for example, blog posts, social media, newspapers, or online articles.

- What criteria you’ll use for inclusion . Here you’ll decide what criteria you’ll use to include content. This can, for instance, be the mentioning of a certain event or advertising a specific product.

- Your parameters . Here, you’ll decide what content you’ll include based on specified parameters in terms of date and location.

The next step is to consider your own pre-conception of the questions and identify your biases. This process is referred to as bracketing and allows you to be aware of your biases before you start your research with the result that they’ll be less likely to influence the analysis.

Your next step would be to define the units of meaning that you’ll code. This will, for example, be the number of times a concept appears in the content or the treatment of concept, words, or themes in the content. You’ll then need to define the set of categories you’ll use for coding which can be either objective or more conceptual.

Based on the above, you’ll then organize the units of meaning into your defined categories. Apart from this, your coding scheme will also determine how you’ll analyze the data.

The next step is to code the content. During this process, you’ll work through the content and record the data according to your coding scheme. It’s also here where conceptual and relational analysis starts to deviate in relation to the process you’ll need to follow.

As mentioned earlier, conceptual analysis aims to identify the number of times a specific concept, idea, word, or phrase appears in the content. So, here, you’ll need to decide what level of analysis you’ll implement.

In contrast, with relational analysis, you’ll need to decide what type of relational analysis you’ll use. So, you’ll need to determine whether you’ll use affect extraction, proximity analysis, cognitive mapping, or a combination of these approaches.

Once you’ve coded the data, you’ll be able to analyze it and draw conclusions from the data based on your research questions.

Content analysis offers an inexpensive and flexible way to identify trends and patterns in communication content. In addition, it’s unobtrusive which eliminates many ethical concerns and inaccuracies in research data. However, to be most effective, a content analysis must be planned and used carefully in order to ensure reliability and validity.

The two general types of content analysis: conceptual and relational analysis . Although these two types follow largely similar processes, their outcomes differ. As such, each of these types can provide different results, interpretations, and conclusions.

In qualitative research coding means categorizing concepts, words, and themes within your content to create a basis for analyzing the results. While coding, you work through the content and record the data according to your coding scheme.

Content analysis is the process of analyzing content and its features with the aim of identifying patterns and the presence of words, themes, and concepts within the content. The goal of a content analysis is to present the trends, patterns, concepts, and ideas in content as objective, quantitative or qualitative data, depending on the specific use case.

Content analysis is a qualitative method of data analysis and can be used in many different fields. It is particularly popular in the social sciences.

It is possible to do qualitative analysis without coding, but content analysis as a method of qualitative analysis requires coding or categorizing data to then analyze it according to your coding scheme in the next step.

What Is Qualitative Content Analysis?

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Reviewed by: Dr Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | February 2021

Overview: Qualitative Content Analysis

- What (exactly) is qualitative content analysis

- The two main types of content analysis

- When to use content analysis

- How to conduct content analysis (the process)

- The advantages and disadvantages of content analysis

1. What is content analysis?

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts such as manuscripts, voice recordings and journals. Content analysis investigates these written, spoken and visual artefacts without explicitly extracting data from participants – this is called unobtrusive research.

In other words, with content analysis, you don’t necessarily need to interact with participants (although you can if necessary); you can simply analyse the data that they have already produced. With this type of analysis, you can analyse data such as text messages, books, Facebook posts, videos, and audio (just to mention a few).

The basics – explicit and implicit content

When working with content analysis, explicit and implicit content will play a role. Explicit data is transparent and easy to identify, while implicit data is that which requires some form of interpretation and is often of a subjective nature. Sounds a bit fluffy? Here’s an example:

Joe: Hi there, what can I help you with?

Lauren: I recently adopted a puppy and I’m worried that I’m not feeding him the right food. Could you please advise me on what I should be feeding?

Joe: Sure, just follow me and I’ll show you. Do you have any other pets?

Lauren: Only one, and it tweets a lot!

In this exchange, the explicit data indicates that Joe is helping Lauren to find the right puppy food. Lauren asks Joe whether she has any pets aside from her puppy. This data is explicit because it requires no interpretation.

On the other hand, implicit data , in this case, includes the fact that the speakers are in a pet store. This information is not clearly stated but can be inferred from the conversation, where Joe is helping Lauren to choose pet food. An additional piece of implicit data is that Lauren likely has some type of bird as a pet. This can be inferred from the way that Lauren states that her pet “tweets”.

As you can see, explicit and implicit data both play a role in human interaction and are an important part of your analysis. However, it’s important to differentiate between these two types of data when you’re undertaking content analysis. Interpreting implicit data can be rather subjective as conclusions are based on the researcher’s interpretation. This can introduce an element of bias , which risks skewing your results.

2. The two types of content analysis

Now that you understand the difference between implicit and explicit data, let’s move on to the two general types of content analysis : conceptual and relational content analysis. Importantly, while conceptual and relational content analysis both follow similar steps initially, the aims and outcomes of each are different.

Conceptual analysis focuses on the number of times a concept occurs in a set of data and is generally focused on explicit data. For example, if you were to have the following conversation:

Marie: She told me that she has three cats.

Jean: What are her cats’ names?

Marie: I think the first one is Bella, the second one is Mia, and… I can’t remember the third cat’s name.

In this data, you can see that the word “cat” has been used three times. Through conceptual content analysis, you can deduce that cats are the central topic of the conversation. You can also perform a frequency analysis , where you assess the term’s frequency in the data. For example, in the exchange above, the word “cat” makes up 9% of the data. In other words, conceptual analysis brings a little bit of quantitative analysis into your qualitative analysis.

As you can see, the above data is without interpretation and focuses on explicit data . Relational content analysis, on the other hand, takes a more holistic view by focusing more on implicit data in terms of context, surrounding words and relationships.

There are three types of relational analysis:

- Affect extraction

- Proximity analysis

- Cognitive mapping

Affect extraction is when you assess concepts according to emotional attributes. These emotions are typically mapped on scales, such as a Likert scale or a rating scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 is “very sad” and 5 is “very happy”.

If participants are talking about their achievements, they are likely to be given a score of 4 or 5, depending on how good they feel about it. If a participant is describing a traumatic event, they are likely to have a much lower score, either 1 or 2.

Proximity analysis identifies explicit terms (such as those found in a conceptual analysis) and the patterns in terms of how they co-occur in a text. In other words, proximity analysis investigates the relationship between terms and aims to group these to extract themes and develop meaning.

Proximity analysis is typically utilised when you’re looking for hard facts rather than emotional, cultural, or contextual factors. For example, if you were to analyse a political speech, you may want to focus only on what has been said, rather than implications or hidden meanings. To do this, you would make use of explicit data, discounting any underlying meanings and implications of the speech.

Lastly, there’s cognitive mapping, which can be used in addition to, or along with, proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping involves taking different texts and comparing them in a visual format – i.e. a cognitive map. Typically, you’d use cognitive mapping in studies that assess changes in terms, definitions, and meanings over time. It can also serve as a way to visualise affect extraction or proximity analysis and is often presented in a form such as a graphic map.

To recap on the essentials, content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts . It involves both conceptual analysis (which is more numbers-based) and relational analysis (which focuses on the relationships between concepts and how they’re connected).

Need a helping hand?

3. When should you use content analysis?

Content analysis is a useful tool that provides insight into trends of communication . For example, you could use a discussion forum as the basis of your analysis and look at the types of things the members talk about as well as how they use language to express themselves. Content analysis is flexible in that it can be applied to the individual, group, and institutional level.

Content analysis is typically used in studies where the aim is to better understand factors such as behaviours, attitudes, values, emotions, and opinions . For example, you could use content analysis to investigate an issue in society, such as miscommunication between cultures. In this example, you could compare patterns of communication in participants from different cultures, which will allow you to create strategies for avoiding misunderstandings in intercultural interactions.

Another example could include conducting content analysis on a publication such as a book. Here you could gather data on the themes, topics, language use and opinions reflected in the text to draw conclusions regarding the political (such as conservative or liberal) leanings of the publication.

4. How to conduct a qualitative content analysis

Conceptual and relational content analysis differ in terms of their exact process ; however, there are some similarities. Let’s have a look at these first – i.e., the generic process:

- Recap on your research questions

- Undertake bracketing to identify biases

- Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

- Code the data and undertake your analysis

Step 1 – Recap on your research questions

It’s always useful to begin a project with research questions , or at least with an idea of what you are looking for. In fact, if you’ve spent time reading this blog, you’ll know that it’s useful to recap on your research questions, aims and objectives when undertaking pretty much any research activity. In the context of content analysis, it’s difficult to know what needs to be coded and what doesn’t, without a clear view of the research questions.

For example, if you were to code a conversation focused on basic issues of social justice, you may be met with a wide range of topics that may be irrelevant to your research. However, if you approach this data set with the specific intent of investigating opinions on gender issues, you will be able to focus on this topic alone, which would allow you to code only what you need to investigate.

Step 2 – Reflect on your personal perspectives and biases

It’s vital that you reflect on your own pre-conception of the topic at hand and identify the biases that you might drag into your content analysis – this is called “ bracketing “. By identifying this upfront, you’ll be more aware of them and less likely to have them subconsciously influence your analysis.

For example, if you were to investigate how a community converses about unequal access to healthcare, it is important to assess your views to ensure that you don’t project these onto your understanding of the opinions put forth by the community. If you have access to medical aid, for instance, you should not allow this to interfere with your examination of unequal access.

Step 3 – Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

Next, you need to operationalise your variables . But what does that mean? Simply put, it means that you have to define each variable or construct . Give every item a clear definition – what does it mean (include) and what does it not mean (exclude). For example, if you were to investigate children’s views on healthy foods, you would first need to define what age group/range you’re looking at, and then also define what you mean by “healthy foods”.

In combination with the above, it is important to create a coding scheme , which will consist of information about your variables (how you defined each variable), as well as a process for analysing the data. For this, you would refer back to how you operationalised/defined your variables so that you know how to code your data.

For example, when coding, when should you code a food as “healthy”? What makes a food choice healthy? Is it the absence of sugar or saturated fat? Is it the presence of fibre and protein? It’s very important to have clearly defined variables to achieve consistent coding – without this, your analysis will get very muddy, very quickly.

Step 4 – Code and analyse the data

The next step is to code the data. At this stage, there are some differences between conceptual and relational analysis.

As described earlier in this post, conceptual analysis looks at the existence and frequency of concepts, whereas a relational analysis looks at the relationships between concepts. For both types of analyses, it is important to pre-select a concept that you wish to assess in your data. Using the example of studying children’s views on healthy food, you could pre-select the concept of “healthy food” and assess the number of times the concept pops up in your data.

Here is where conceptual and relational analysis start to differ.

At this stage of conceptual analysis , it is necessary to decide on the level of analysis you’ll perform on your data, and whether this will exist on the word, phrase, sentence, or thematic level. For example, will you code the phrase “healthy food” on its own? Will you code each term relating to healthy food (e.g., broccoli, peaches, bananas, etc.) with the code “healthy food” or will these be coded individually? It is very important to establish this from the get-go to avoid inconsistencies that could result in you having to code your data all over again.

On the other hand, relational analysis looks at the type of analysis. So, will you use affect extraction? Proximity analysis? Cognitive mapping? A mix? It’s vital to determine the type of analysis before you begin to code your data so that you can maintain the reliability and validity of your research .

How to conduct conceptual analysis

First, let’s have a look at the process for conceptual analysis.

Once you’ve decided on your level of analysis, you need to establish how you will code your concepts, and how many of these you want to code. Here you can choose whether you want to code in a deductive or inductive manner. Just to recap, deductive coding is when you begin the coding process with a set of pre-determined codes, whereas inductive coding entails the codes emerging as you progress with the coding process. Here it is also important to decide what should be included and excluded from your analysis, and also what levels of implication you wish to include in your codes.

For example, if you have the concept of “tall”, can you include “up in the clouds”, derived from the sentence, “the giraffe’s head is up in the clouds” in the code, or should it be a separate code? In addition to this, you need to know what levels of words may be included in your codes or not. For example, if you say, “the panda is cute” and “look at the panda’s cuteness”, can “cute” and “cuteness” be included under the same code?

Once you’ve considered the above, it’s time to code the text . We’ve already published a detailed post about coding , so we won’t go into that process here. Once you’re done coding, you can move on to analysing your results. This is where you will aim to find generalisations in your data, and thus draw your conclusions .

How to conduct relational analysis

Now let’s return to relational analysis.

As mentioned, you want to look at the relationships between concepts . To do this, you’ll need to create categories by reducing your data (in other words, grouping similar concepts together) and then also code for words and/or patterns. These are both done with the aim of discovering whether these words exist, and if they do, what they mean.

Your next step is to assess your data and to code the relationships between your terms and meanings, so that you can move on to your final step, which is to sum up and analyse the data.

To recap, it’s important to start your analysis process by reviewing your research questions and identifying your biases . From there, you need to operationalise your variables, code your data and then analyse it.

5. What are the pros & cons of content analysis?

One of the main advantages of content analysis is that it allows you to use a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods, which results in a more scientifically rigorous analysis.

For example, with conceptual analysis, you can count the number of times that a term or a code appears in a dataset, which can be assessed from a quantitative standpoint. In addition to this, you can then use a qualitative approach to investigate the underlying meanings of these and relationships between them.

Content analysis is also unobtrusive and therefore poses fewer ethical issues than some other analysis methods. As the content you’ll analyse oftentimes already exists, you’ll analyse what has been produced previously, and so you won’t have to collect data directly from participants. When coded correctly, data is analysed in a very systematic and transparent manner, which means that issues of replicability (how possible it is to recreate research under the same conditions) are reduced greatly.

On the downside , qualitative research (in general, not just content analysis) is often critiqued for being too subjective and for not being scientifically rigorous enough. This is where reliability (how replicable a study is by other researchers) and validity (how suitable the research design is for the topic being investigated) come into play – if you take these into account, you’ll be on your way to achieving sound research results.

Recap: Qualitative content analysis

In this post, we’ve covered a lot of ground – click on any of the sections to recap:

If you have any questions about qualitative content analysis, feel free to leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your qualitative content analysis, be sure to book an initial consultation with one of our friendly Research Coaches.

Learn More About Qualitative:

Triangulation: The Ultimate Credibility Enhancer

Triangulation is one of the best ways to enhance the credibility of your research. Learn about the different options here.

Structured, Semi-Structured & Unstructured Interviews

Learn about the differences (and similarities) between the three interview approaches: structured, semi-structured and unstructured.

Qualitative Coding Examples: Process, Values & In Vivo Coding

See real-world examples of qualitative data that has been coded using process coding, values coding and in vivo coding.

In Vivo Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about in vivo coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies where the nuances of language are central to the aims.

Process Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about process coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies exploring processes, actions and changes over time.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

19 Comments

If I am having three pre-decided attributes for my research based on which a set of semi-structured questions where asked then should I conduct a conceptual content analysis or relational content analysis. please note that all three attributes are different like Agility, Resilience and AI.

Thank you very much. I really enjoyed every word.

please send me one/ two sample of content analysis

send me to any sample of qualitative content analysis as soon as possible

Many thanks for the brilliant explanation. Do you have a sample practical study of a foreign policy using content analysis?

1) It will be very much useful if a small but complete content analysis can be sent, from research question to coding and analysis. 2) Is there any software by which qualitative content analysis can be done?

Common software for qualitative analysis is nVivo, and quantitative analysis is IBM SPSS

Thank you. Can I have at least 2 copies of a sample analysis study as my reference?

Could you please send me some sample of textbook content analysis?

Can I send you my research topic, aims, objectives and questions to give me feedback on them?

please could you send me samples of content analysis?

Yes please send

really we enjoyed your knowledge thanks allot. from Ethiopia

can you please share some samples of content analysis(relational)? I am a bit confused about processing the analysis part

Is it possible for you to list the journal articles and books or other sources you used to write this article? Thank you.

can you please send some samples of content analysis ?

can you kindly send some good examples done by using content analysis ?

This was very useful. can you please send me sample for qualitative content analysis. thank you

What a brilliant explanation! Kindly help with textbooks or blogs on the context analysis method such as discourse, thematic and semiotic analysis.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within some given qualitative data (i.e. text). Using content analysis, researchers can quantify and analyze the presence, meanings, and relationships of such certain words, themes, or concepts. As an example, researchers can evaluate language used within a news article to search for bias or partiality. Researchers can then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of surrounding the text.

Description

Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents). A single study may analyze various forms of text in its analysis. To analyze the text using content analysis, the text must be coded, or broken down, into manageable code categories for analysis (i.e. “codes”). Once the text is coded into code categories, the codes can then be further categorized into “code categories” to summarize data even further.

Three different definitions of content analysis are provided below.

Definition 1: “Any technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages.” (from Holsti, 1968)

Definition 2: “An interpretive and naturalistic approach. It is both observational and narrative in nature and relies less on the experimental elements normally associated with scientific research (reliability, validity, and generalizability) (from Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry, 1994-2012).

Definition 3: “A research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication.” (from Berelson, 1952)

Uses of Content Analysis

Identify the intentions, focus or communication trends of an individual, group or institution

Describe attitudinal and behavioral responses to communications

Determine the psychological or emotional state of persons or groups

Reveal international differences in communication content

Reveal patterns in communication content

Pre-test and improve an intervention or survey prior to launch

Analyze focus group interviews and open-ended questions to complement quantitative data

Types of Content Analysis

There are two general types of content analysis: conceptual analysis and relational analysis. Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of concepts in a text. Relational analysis develops the conceptual analysis further by examining the relationships among concepts in a text. Each type of analysis may lead to different results, conclusions, interpretations and meanings.

Conceptual Analysis

Typically people think of conceptual analysis when they think of content analysis. In conceptual analysis, a concept is chosen for examination and the analysis involves quantifying and counting its presence. The main goal is to examine the occurrence of selected terms in the data. Terms may be explicit or implicit. Explicit terms are easy to identify. Coding of implicit terms is more complicated: you need to decide the level of implication and base judgments on subjectivity (an issue for reliability and validity). Therefore, coding of implicit terms involves using a dictionary or contextual translation rules or both.

To begin a conceptual content analysis, first identify the research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. Next, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. This is basically a process of selective reduction. By reducing the text to categories, the researcher can focus on and code for specific words or patterns that inform the research question.

General steps for conducting a conceptual content analysis:

1. Decide the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes

2. Decide how many concepts to code for: develop a pre-defined or interactive set of categories or concepts. Decide either: A. to allow flexibility to add categories through the coding process, or B. to stick with the pre-defined set of categories.

Option A allows for the introduction and analysis of new and important material that could have significant implications to one’s research question.

Option B allows the researcher to stay focused and examine the data for specific concepts.

3. Decide whether to code for existence or frequency of a concept. The decision changes the coding process.

When coding for the existence of a concept, the researcher would count a concept only once if it appeared at least once in the data and no matter how many times it appeared.

When coding for the frequency of a concept, the researcher would count the number of times a concept appears in a text.

4. Decide on how you will distinguish among concepts:

Should text be coded exactly as they appear or coded as the same when they appear in different forms? For example, “dangerous” vs. “dangerousness”. The point here is to create coding rules so that these word segments are transparently categorized in a logical fashion. The rules could make all of these word segments fall into the same category, or perhaps the rules can be formulated so that the researcher can distinguish these word segments into separate codes.

What level of implication is to be allowed? Words that imply the concept or words that explicitly state the concept? For example, “dangerous” vs. “the person is scary” vs. “that person could cause harm to me”. These word segments may not merit separate categories, due the implicit meaning of “dangerous”.

5. Develop rules for coding your texts. After decisions of steps 1-4 are complete, a researcher can begin developing rules for translation of text into codes. This will keep the coding process organized and consistent. The researcher can code for exactly what he/she wants to code. Validity of the coding process is ensured when the researcher is consistent and coherent in their codes, meaning that they follow their translation rules. In content analysis, obeying by the translation rules is equivalent to validity.

6. Decide what to do with irrelevant information: should this be ignored (e.g. common English words like “the” and “and”), or used to reexamine the coding scheme in the case that it would add to the outcome of coding?

7. Code the text: This can be done by hand or by using software. By using software, researchers can input categories and have coding done automatically, quickly and efficiently, by the software program. When coding is done by hand, a researcher can recognize errors far more easily (e.g. typos, misspelling). If using computer coding, text could be cleaned of errors to include all available data. This decision of hand vs. computer coding is most relevant for implicit information where category preparation is essential for accurate coding.

8. Analyze your results: Draw conclusions and generalizations where possible. Determine what to do with irrelevant, unwanted, or unused text: reexamine, ignore, or reassess the coding scheme. Interpret results carefully as conceptual content analysis can only quantify the information. Typically, general trends and patterns can be identified.

Relational Analysis

Relational analysis begins like conceptual analysis, where a concept is chosen for examination. However, the analysis involves exploring the relationships between concepts. Individual concepts are viewed as having no inherent meaning and rather the meaning is a product of the relationships among concepts.

To begin a relational content analysis, first identify a research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. The research question must be focused so the concept types are not open to interpretation and can be summarized. Next, select text for analysis. Select text for analysis carefully by balancing having enough information for a thorough analysis so results are not limited with having information that is too extensive so that the coding process becomes too arduous and heavy to supply meaningful and worthwhile results.

There are three subcategories of relational analysis to choose from prior to going on to the general steps.

Affect extraction: an emotional evaluation of concepts explicit in a text. A challenge to this method is that emotions can vary across time, populations, and space. However, it could be effective at capturing the emotional and psychological state of the speaker or writer of the text.

Proximity analysis: an evaluation of the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. Text is defined as a string of words called a “window” that is scanned for the co-occurrence of concepts. The result is the creation of a “concept matrix”, or a group of interrelated co-occurring concepts that would suggest an overall meaning.

Cognitive mapping: a visualization technique for either affect extraction or proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping attempts to create a model of the overall meaning of the text such as a graphic map that represents the relationships between concepts.

General steps for conducting a relational content analysis:

1. Determine the type of analysis: Once the sample has been selected, the researcher needs to determine what types of relationships to examine and the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes. 2. Reduce the text to categories and code for words or patterns. A researcher can code for existence of meanings or words. 3. Explore the relationship between concepts: once the words are coded, the text can be analyzed for the following:

Strength of relationship: degree to which two or more concepts are related.

Sign of relationship: are concepts positively or negatively related to each other?

Direction of relationship: the types of relationship that categories exhibit. For example, “X implies Y” or “X occurs before Y” or “if X then Y” or if X is the primary motivator of Y.

4. Code the relationships: a difference between conceptual and relational analysis is that the statements or relationships between concepts are coded. 5. Perform statistical analyses: explore differences or look for relationships among the identified variables during coding. 6. Map out representations: such as decision mapping and mental models.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability : Because of the human nature of researchers, coding errors can never be eliminated but only minimized. Generally, 80% is an acceptable margin for reliability. Three criteria comprise the reliability of a content analysis:

Stability: the tendency for coders to consistently re-code the same data in the same way over a period of time.

Reproducibility: tendency for a group of coders to classify categories membership in the same way.

Accuracy: extent to which the classification of text corresponds to a standard or norm statistically.

Validity : Three criteria comprise the validity of a content analysis:

Closeness of categories: this can be achieved by utilizing multiple classifiers to arrive at an agreed upon definition of each specific category. Using multiple classifiers, a concept category that may be an explicit variable can be broadened to include synonyms or implicit variables.

Conclusions: What level of implication is allowable? Do conclusions correctly follow the data? Are results explainable by other phenomena? This becomes especially problematic when using computer software for analysis and distinguishing between synonyms. For example, the word “mine,” variously denotes a personal pronoun, an explosive device, and a deep hole in the ground from which ore is extracted. Software can obtain an accurate count of that word’s occurrence and frequency, but not be able to produce an accurate accounting of the meaning inherent in each particular usage. This problem could throw off one’s results and make any conclusion invalid.

Generalizability of the results to a theory: dependent on the clear definitions of concept categories, how they are determined and how reliable they are at measuring the idea one is seeking to measure. Generalizability parallels reliability as much of it depends on the three criteria for reliability.

Advantages of Content Analysis

Directly examines communication using text

Allows for both qualitative and quantitative analysis

Provides valuable historical and cultural insights over time

Allows a closeness to data

Coded form of the text can be statistically analyzed

Unobtrusive means of analyzing interactions

Provides insight into complex models of human thought and language use

When done well, is considered a relatively “exact” research method

Content analysis is a readily-understood and an inexpensive research method

A more powerful tool when combined with other research methods such as interviews, observation, and use of archival records. It is very useful for analyzing historical material, especially for documenting trends over time.

Disadvantages of Content Analysis

Can be extremely time consuming

Is subject to increased error, particularly when relational analysis is used to attain a higher level of interpretation

Is often devoid of theoretical base, or attempts too liberally to draw meaningful inferences about the relationships and impacts implied in a study

Is inherently reductive, particularly when dealing with complex texts

Tends too often to simply consist of word counts

Often disregards the context that produced the text, as well as the state of things after the text is produced

Can be difficult to automate or computerize

Textbooks & Chapters

Berelson, Bernard. Content Analysis in Communication Research.New York: Free Press, 1952.

Busha, Charles H. and Stephen P. Harter. Research Methods in Librarianship: Techniques and Interpretation.New York: Academic Press, 1980.

de Sola Pool, Ithiel. Trends in Content Analysis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1959.

Krippendorff, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

Fielding, NG & Lee, RM. Using Computers in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, 1991. (Refer to Chapter by Seidel, J. ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’.)

Methodological Articles

Hsieh HF & Shannon SE. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.Qualitative Health Research. 15(9): 1277-1288.

Elo S, Kaarianinen M, Kanste O, Polkki R, Utriainen K, & Kyngas H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 4:1-10.

Application Articles

Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, & Phillips T. (2011). iPhone Apps for Smoking Cessation: A content analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 40(3):279-285.

Ullstrom S. Sachs MA, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, & Brommels M. (2014). Suffering in Silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. British Medical Journal, Quality & Safety Issue. 23:325-331.

Owen P. (2012).Portrayals of Schizophrenia by Entertainment Media: A Content Analysis of Contemporary Movies. Psychiatric Services. 63:655-659.

Choosing whether to conduct a content analysis by hand or by using computer software can be difficult. Refer to ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’ listed above in “Textbooks and Chapters” for a discussion of the issue.

QSR NVivo: http://www.qsrinternational.com/products.aspx

Atlas.ti: http://www.atlasti.com/webinars.html

R- RQDA package: http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/

Rolly Constable, Marla Cowell, Sarita Zornek Crawford, David Golden, Jake Hartvigsen, Kathryn Morgan, Anne Mudgett, Kris Parrish, Laura Thomas, Erika Yolanda Thompson, Rosie Turner, and Mike Palmquist. (1994-2012). Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University. Available at: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=63 .

As an introduction to Content Analysis by Michael Palmquist, this is the main resource on Content Analysis on the Web. It is comprehensive, yet succinct. It includes examples and an annotated bibliography. The information contained in the narrative above draws heavily from and summarizes Michael Palmquist’s excellent resource on Content Analysis but was streamlined for the purpose of doctoral students and junior researchers in epidemiology.

At Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, more detailed training is available through the Department of Sociomedical Sciences- P8785 Qualitative Research Methods.

Join the Conversation

Have a question about methods? Join us on Facebook

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual: Books, newspapers and magazines. Speeches and interviews. Web content and social media posts. Photographs and films.

To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual: Books, newspapers, and magazines. Speeches and interviews. Web content and social media posts. Photographs and films.

Content analysis is the process of analyzing content and its features with the aim of identifying patterns and the presence of words, themes, and concepts within the content. The goal of a content analysis is to present the trends, patterns, concepts, and ideas in content as objective, quantitative or qualitative data, depending on the specific ...

How to conduct content analysis (the process) The advantages and disadvantages of content analysis. 1. What is content analysis? Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts such as manuscripts, voice recordings and journals.

Writing@CSU Guide. Using Content Analysis. This guide provides an introduction to content analysis, a research methodology that examines words or phrases within a wide range of texts. Introduction to Content Analysis: Read about the history and uses of content analysis.

To begin a conceptual content analysis, first identify the research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. Next, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. This is basically a process of selective reduction.