Everything We Know About Facebook’s Secret Mood-Manipulation Experiment

It was probably legal. But was it ethical?

Updated, 09/08/14

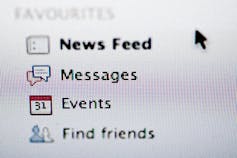

Facebook’s News Feed—the main list of status updates, messages, and photos you see when you open Facebook on your computer or phone—is not a perfect mirror of the world.

But few users expect that Facebook would change its News Feed in order to manipulate their emotional state.

We now know that’s exactly what happened two years ago. For one week in January 2012, data scientists skewed what almost 700,000 Facebook users saw when they logged into its service. Some people were shown content with a preponderance of happy and positive words; some were shown content analyzed as sadder than average. And when the week was over, these manipulated users were more likely to post either especially positive or negative words themselves.

This tinkering was just revealed as part of a new study , published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Many previous studies have used Facebook data to examine “emotional contagion,” as this one did. This study is different because, while other studies have observed Facebook user data, this one set out to manipulate them.

The experiment is almost certainly legal. In the company’s current terms of service, Facebook users relinquish the use of their data for “data analysis, testing, [and] research.” Is it ethical, though? Since news of the study first emerged, I’ve seen and heard both privacy advocates and casual users express surprise at the audacity of the experiment.

In the wake of both the Snowden stuff and the Cuba twitter stuff, the Facebook “transmission of anger” experiment is terrifying. — Clay Johnson (@cjoh) June 28, 2014

Get off Facebook. Get your family off Facebook. If you work there, quit. They’re fucking awful. — Erin Kissane (@kissane) June 28, 2014

We’re tracking the ethical, legal, and philosophical response to this Facebook experiment here. We’ve also asked the authors of the study for comment. Author Jamie Guillory replied and referred us to a Facebook spokesman. Early Sunday morning, a Facebook spokesman sent this comment in an email:

This research was conducted for a single week in 2012 and none of the data used was associated with a specific person’s Facebook account. We do research to improve our services and to make the content people see on Facebook as relevant and engaging as possible. A big part of this is understanding how people respond to different types of content, whether it’s positive or negative in tone, news from friends, or information from pages they follow. We carefully consider what research we do and have a strong internal review process. There is no unnecessary collection of people’s data in connection with these research initiatives and all data is stored securely.

And on Sunday afternoon, Adam D.I. Kramer, one of the study’s authors and a Facebook employee, commented on the experiment in a public Facebook post. “And at the end of the day, the actual impact on people in the experiment was the minimal amount to statistically detect it,” he writes. “Having written and designed this experiment myself, I can tell you that our goal was never to upset anyone … In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.”

Kramer adds that Facebook’s internal review practices have “come a long way” since 2012, when the experiment was run.

What did the paper itself find?

The study found that by manipulating the News Feeds displayed to 689,003 Facebook users, it could affect the content that those users posted to Facebook. More negative News Feeds led to more negative status messages, as more positive News Feeds led to positive statuses.

As far as the study was concerned, this meant that it had shown “that emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness.” It touts that this emotional contagion can be achieved without “direct interaction between people” (because the unwitting subjects were only seeing each others’ News Feeds).

The researchers add that never during the experiment could they read individual users’ posts.

Two interesting things stuck out to me in the study.

The first? The effect the study documents is very small, as little as one-tenth of a percent of an observed change. That doesn’t mean it’s unimportant, though, as the authors add:

Given the massive scale of social networks such as Facebook, even small effects can have large aggregated consequences … After all, an effect size of d = 0.001 at Facebook’s scale is not negligible: In early 2013, this would have corresponded to hundreds of thousands of emotion expressions in status updates per day .

The second was this line:

Omitting emotional content reduced the amount of words the person subsequently produced, both when positivity was reduced (z = −4.78, P < 0.001) and when negativity was reduced (z = −7.219, P < 0.001).

In other words, when researchers reduced the appearance of either positive or negative sentiments in people’s News Feeds—when the feeds just got generally less emotional—those people stopped writing so many words on Facebook.

Make people’s feeds blander and they stop typing things into Facebook.

Was the study well designed? Perhaps not, says John Grohol, the founder of psychology website Psych Central. Grohol believes the study’s methods are hampered by the misuse of tools: Software better matched to analyze novels and essays, he says, is being applied toward the much shorter texts on social networks.

Let’s look at two hypothetical examples of why this is important. Here are two sample tweets (or status updates) that are not uncommon: “I am not happy.” “I am not having a great day.” An independent rater or judge would rate these two tweets as negative—they’re clearly expressing a negative emotion. That would be +2 on the negative scale, and 0 on the positive scale. But the LIWC 2007 tool doesn’t see it that way. Instead, it would rate these two tweets as scoring +2 for positive (because of the words “great” and “happy”) and +2 for negative (because of the word “not” in both texts).

“What the Facebook researchers clearly show,” writes Grohol, “is that they put too much faith in the tools they’re using without understanding—and discussing—the tools’ significant limitations.”

Did an institutional review board (IRB)—an independent ethics committee that vets research that involves humans—approve the experiment?

According to a Cornell University press statement on Monday, the experiment was conducted before an IRB was consulted. * Cornell professor Jeffrey Hancock—an author of the study—began working on the results after Facebook had conducted the experiment. Hancock only had access to results, says the release, so “Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board concluded that he was not directly engaged in human research and that no review by the Cornell Human Research Protection Program was required.”

In other words, the experiment had already been run, so its human subjects were beyond protecting. Assuming the researchers did not see users’ confidential data, the results of the experiment could be examined without further endangering any subjects.

Both Cornell and Facebook have been reluctant to provide details about the process beyond their respective prepared statements. One of the study's authors told The Atlantic on Monday that he’s been advised by the university not to speak to reporters.

By the time the study reached Susan Fiske, the Princeton University psychology professor who edited the study for publication, Cornell’s IRB members had already determined it outside of their purview.

Fiske had earlier conveyed to The Atlantic that the experiment was IRB-approved.

“I was concerned,” Fiske told The Atlantic on Saturday , “ until I queried the authors and they said their local institutional review board had approved it—and apparently on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.”

On Sunday, other reports raised questions about how an IRB was consulted. In a Facebook post on Sunday, study author Adam Kramer referenced only “internal review practices.” And a Forbes report that day, citing an unnamed source, claimed that Facebook only used an internal review.

When The Atlantic asked Fiske to clarify Sunday, she said the researchers’ “revision letter said they had Cornell IRB approval as a ‘pre-existing dataset’ presumably from FB, who seems to have reviewed it as well in some unspecified way … Under IRB regulations, pre-existing dataset would have been approved previously and someone is just analyzing data already collected, often by someone else.”

The mention of a “pre-existing dataset” here matters because, as Fiske explained in a follow-up email, “presumably the data already existed when they applied to Cornell IRB.” (She also noted: “I am not second-guessing the decision.”) Cornell’s Monday statement confirms this presumption.

On Saturday, Fiske said that she didn’t want the “the originality of the research” to be lost, but called the experiment “an open ethical question.”

“It’s ethically okay from the regulations perspective, but ethics are kind of social decisions. There’s not an absolute answer. And so the level of outrage that appears to be happening suggests that maybe it shouldn’t have been done … I’m still thinking about it and I’m a little creeped out, too.”

For more, check Atlantic editor Adrienne LaFrance’s full interview with Prof. Fiske .

From what we know now, were the experiment’s subjects able to provide informed consent?

In its ethical principles and code of conduct , the American Psychological Association (APA) defines informed consent like this:

When psychologists conduct research or provide assessment, therapy, counseling, or consulting services in person or via electronic transmission or other forms of communication, they obtain the informed consent of the individual or individuals using language that is reasonably understandable to that person or persons except when conducting such activities without consent is mandated by law or governmental regulation or as otherwise provided in this Ethics Code.

As mentioned above, the research seems to have been carried out under Facebook’s extensive terms of service. The company’s current data-use policy, which governs exactly how it may use users’ data, runs to more than 9,000 words and uses the word research twice. But as Forbes writer Kashmir Hill reported Monday night , the data-use policy in effect when the experiment was conducted never mentioned “research” at all— the word wasn’t inserted until May 2012 .

Never mind whether the current data-use policy constitutes “language that is reasonably understandable”: Under the January 2012 terms of service, did Facebook secure even shaky consent?

The APA has further guidelines for so-called deceptive research like this, where the real purpose of the research can’t be made available to participants during research. The last of these guidelines is:

Psychologists explain any deception that is an integral feature of the design and conduct of an experiment to participants as early as is feasible, preferably at the conclusion of their participation, but no later than at the conclusion of the data collection, and permit participants to withdraw their data.

At the end of the experiment, did Facebook tell the user-subjects that their News Feeds had been altered for the sake of research? If so, the study never mentions it.

James Grimmelmann, a law professor at the University of Maryland, believes the study did not secure informed consent. And he adds that Facebook fails even its own standards , which are lower than that of the academy:

A stronger reason is that even when Facebook manipulates our News Feeds to sell us things, it is supposed—legally and ethically—to meet certain minimal standards. Anything on Facebook that is actually an ad is labelled as such (even if not always clearly.) This study failed even that test, and for a particularly unappealing research goal: We wanted to see if we could make you feel bad without you noticing. We succeeded .

Did the U.S. government sponsor the research?

Cornell has now updated its June 10 story to say that the research received no external funding. Originally, Cornell had identified the Army Research Office, an agency within the U.S. Army that funds basic research in the military’s interest, as one of the funders of the experiment.

Do these kind of News Feed tweaks happen at other times?

At any one time, Facebook said last year, there were on average 1,500 pieces of content that could show up in your News Feed. The company uses an algorithm to determine what to display and what to hide.

It talks about this algorithm very rarely, but we know it’s very powerful. Last year, the company changed News Feed to surface more news stories. Websites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy proceeded to see record-busting numbers of visitors.

So we know it happens. Consider Fiske’s explanation of the research ethics here—the study was approved “on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.” And consider also that from this study alone Facebook knows at least one knob to tweak to get users to post more words on Facebook.

* This post originally stated that an institutional review board, or IRB, was consulted before the experiment took place regarding certain aspects of data collection.

Adrienne LaFrance contributed writing and reporting.

About the Author

More Stories

The World Could Be Entering a New Era of Climate War

Wait, Why Wasn’t There a Climate Backlash?

- The Big Story

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Everything You Need to Know About Facebook's Controversial Emotion Experiment

The closest any of us who might have participated in Facebook's huge social engineering study came to actually consenting to participate was signing up for the service. Facebook's Data Use Policy warns users that Facebook “may use the information we receive about you…for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.” This has led to charges that the study violated laws designed to protect human research subjects. But it turns out that those laws don’t apply to the study, and even if they did, it could have been approved, perhaps with some tweaks. Why this is the case requires a bit of explanation.

#### Michelle N. Meyer

##### About

[Michelle N. Meyer](http://www.michellenmeyer.com/) is an Assistant Professor and Director of Bioethics Policy in the Union Graduate College-Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Bioethics Program, where she writes and teaches at the intersection of law, science, and philosophy. She is a member of the board of three non-profit organizations devoted to scientific research, including the Board of Directors of [PersonalGenomes.org](http://personalgenomes.org/).

For one week in 2012, Facebook altered the algorithms it uses to determine which status updates appeared in the News Feed of 689,003 randomly selected users (about 1 of every 2,500 Facebook users). The results of this study were just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

As the authors explain, “[b]ecause people’s friends frequently produce much more content than one person can view,” Facebook ordinarily filters News Feed content “via a ranking algorithm that Facebook continually develops and tests in the interest of showing viewers the content they will find most relevant and engaging.” In this study, the algorithm filtered content based on its emotional content. A post was identified as “positive” or “negative” if it used at least one word identified as positive or negative by software (run automatically without researchers accessing users’ text).

Some critics of the experiment have characterized it as one in which the researchers intentionally tried “to make users sad.” With the benefit of hindsight, they claim that the study merely tested the perfectly obvious proposition that reducing the amount of positive content in a user’s News Feed would cause that user to use more negative words and fewer positive words themselves and/or to become less happy (more on the gap between these effects in a minute). But that’s *not *what some prior studies would have predicted.

Previous studies both in the U.S. and in Germany had found that the largely positive, often self-promotional content that Facebook tends to feature has made users feel bitter and resentful---a phenomenon the German researchers memorably call “the self-promotion-envy spiral.” Those studies would have predicted that reducing the positive content in a user’s feed might actually make users less sad. And it makes sense that Facebook would want to determine what will make users spend more time on its site rather than close that tab in disgust or despair. The study’s first author, Adam Kramer of Facebook, confirms ---on Facebook, of course---that they did indeed want to investigate the theory that seeing friends’ positive content makes users sad.

To do so, the researchers conducted two experiments, with a total of four groups of users (about 155,000 each). In the first experiment, Facebook reduced the positive content of News Feeds. Each positive post “had between a 10-percent and 90-percent chance (based on their User ID) of being omitted from their News Feed for that specific viewing.” In the second experiment, Facebook reduced the negative content of News Feeds in the same manner. In both experiments, these treatment conditions were compared with control conditions in which a similar portion of posts were randomly filtered out (i.e., without regard to emotional content). Note that whatever negativity users were exposed to came from their own friends, not, somehow, from Facebook engineers. In the first, presumably most objectionable, experiment, the researchers chose to filter out varying amounts (10 percent to 90 percent) of friends’ positive content, thereby leaving a News Feed more concentrated with posts in which a user’s friend had written at least one negative word.

The results:

[f]or people who had positive content reduced in their News Feed, a larger percentage of words in people’s status updates were negative and a smaller percentage were positive. When negativity was reduced, the opposite pattern occurred. These results suggest that the emotions expressed by friends, via online social networks, influence our own moods, constituting, to our knowledge, the first experimental evidence for massive-scale emotional contagion via social networks.

Note two things. First, while statistically significant, these effect sizes are, as the authors acknowledge, quite small. The largest effect size was a mere two hundredths of a standard deviation (d = .02). The smallest was one thousandth of a standard deviation (d = .001). The authors suggest that their findings are primarily significant for public health purposes, because when the aggregated, even small individual effects can have large social consequences.

Second, although the researchers conclude that their experiments constitute evidence of “social contagion” ---that is, that “emotional states can be transferred to others”--- this overstates what they could possibly know from this study. The fact that someone exposed to positive words very slightly increased the amount of positive words that she then used in her Facebook posts does not necessarily mean that this change in her News Feed content caused any change in her mood . The very slight increase in the use of positive words could simply be a matter of keeping up (or down, in the case of the reduced positivity experiment) with the Joneses. It seems highly likely that Facebook users experience (varying degrees of) pressure to conform to social norms about acceptable levels of snark and kvetching---and of bragging and pollyannaisms. Someone who is already internally grumbling about how United Statesians are, like, such total posers during the World Cup may feel freer to voice that complaint on Facebook than when his feed was more densely concentrated with posts of the “human beings are so great and I feel so lucky to know you all---group hug! feel any worse than they otherwise would have, much less for any increase in negative affect that may have occurred to have risen to the level of a mental health crisis, as some have suggested.

One threshold question in determining whether this study required ethical approval by an Internal Review Board is whether it constituted “human subjects research.” An activity is considered “ research ” under the federal regulations, if it is “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.” The study was plenty systematic, and it was designed to investigate the “self-promotion-envy spiral” theory of social networks. Check.

As defined by the regulations, a “human subject” is “a living individual about whom an investigator... obtains,” inter alia, “data through intervention.” Intervention, in turn, includes “manipulations of the subject or the subject’s environment that are performed for research purposes.” According to guidance issued by the Office for Human Research Protection s (OHRP), the federal agency tasked with overseeing application of the regulations to HHS-conducted and –funded human subjects research, “orchestrating environmental events or social interactions” constitutes manipulation.

I suppose one could argue---in the tradition of choice architecture---that to say that Facebook manipulated its users’ environment is a near tautology. Facebook employs algorithms to filter News Feeds, which it apparently regularly tweaks in an effort to maximize user satisfaction, ideal ad placement, and so on. It may be that Facebook regularly changes the algorithms that determine how a user experiences her News Feed.

Given this baseline of constant manipulation, you could say that this study did not involve any incremental additional manipulation. No manipulation, no intervention. No intervention, no human subjects. No human subjects, no federal regulations requiring IRB approval. But…

That doesn’t mean that moving from one algorithm to the next doesn’t constitute a manipulation of the user’s environment. Therefore, I assume that this study meets the federal definition of “human subjects research” (HSR).

Importantly---and contrary to the apparent beliefs of some commentators---not all HSR is subject to the federal regulations, including IRB review. By the terms of the regulations themselves , HSR is subject to IRB review only when it is conducted or funded by any of several federal departments and agencies (so-called Common Rule agencies), or when it will form the basis of an FDA marketing application . HSR conducted and funded solely by entities like Facebook is not subject to federal research regulations.

But this study was not conducted by Facebook alone; the second and third authors on the paper have appointments at the University of California, San Francisco, and Cornell, respectively. Although some commentators assume that university research is only subject to the federal regulations when that research is funded by the government, this, too, is incorrect. Any college or university that accepts any research funds from any Common Rule agency must sign a Federalwide Assurance (FWA) , a boilerplate contract between the institution and OHRP in which the institution identifies the duly-formed and registered IRB that will review the funded research. The FWA invites institutions to voluntarily commit to extend the requirement of IRB review from funded projects to all human subject research in which the institution is engaged, regardless of the source of funding. Historically, the vast majority of colleges and universities have agreed to “check the box,” as it’s called. If you are a student or a faculty member at an institution that has checked the box, then any HSR you conduct must be approved by an IRB.

As I recently had occasion to discover , Cornell has indeed checked the box ( see #5 here ). UCSF appears to have done so , as well, although it’s possible that it simply requires IRB review of all HSR by institutional policy, rather than FWA contract.

But these FWAs only require IRB review if the two authors’ participation in the Facebook study meant that Cornell and UCSF were “engaged” in research. When an institution is “engaged in research” turns out to be an important legal question in much collaborative research, and one the Common Rule itself doesn’t address. OHRP, however, has issued (non-binding, of course) guidance on the matter. The general rule is that an institution is engaged in research when its employee or agent obtains data about subjects through intervention or interaction, identifiable private information about subjects, or subjects’ informed consent.

According to the author contributions section of the PNAS paper, the Facebook-affiliated author “performed [the] research” and “analyzed [the] data.” The two academic authors merely helped him design the research and write the paper. They would not seem to have been involved, then, in obtaining either data or informed consent. (And even if the academic authors had gotten their hands on individualized data, so long as that data remained coded by Facebook user ID numbers that did not allow them to readily ascertain subjects’ identities, OHRP would not consider them to have been engaged in research.)

>Because the two academic authors merely designed the research and wrote the paper, they would not seem to have been involved, then, in obtaining either data or informed consent.

It would seem, then, that neither UCSF nor Cornell was "engaged in research" and, since Facebook was engaged in HSR but is not subject to the federal regulations, that IRB approval was not required. Whether that’s a good or a bad thing is a separate question, of course. (A previous report that the Cornell researcher had received funding from the Army Research Office, which as part of the Department of Defense, a Common Rule agency, would have triggered IRB review, has been retracted.) In fact, as this piece went to press on Monday afternoon, Cornell’s media relations had just issued a statement that provided exactly this explanation for why it determined that IRB review was not required.

Princeton psychologist Susan Fiske, who edited the PNAS article, told a Los Angeles Times reporter the following :

But then Forbes reported that Fiske “misunderstood the nature of the approval. A source familiar with the matter says the study was approved only through an internal review process at Facebook, not through a university Institutional Review Board.”

Most recently, Fiske told the Atlantic that Cornell's IRB did indeed review the study, and approved it as having involved a "pre-existing dataset." Given that, according to the PNAS paper, the two academic researchers collaborated with the Facebook researcher in designing the research, it strikes me as disingenuous to claim that the dataset preexisted the academic researchers' involvement. As I suggested above, however, it does strike me as correct to conclude that, given the academic researchers' particular contributions to the study, neither UCSF nor Cornell was engaged in research, and hence that IRB review was not required at all.

>It strikes me as disingenuous to claim that the dataset preexisted the academic researchers' involvement.

But if an IRB had reviewed it, could it have approved it, consistent with a plausible interpretation of the Common Rule? The answer, I think, is Yes, although under the federal regulations, the study ought to have required a bit more informed consent than was present here (about which more below).

Many have expressed outrage that any IRB could approve this study, and there has been speculation about the possible grounds the IRB might have given. The Atlantic suggests that the “experiment is almost certainly legal. In the company’s current terms of service, Facebook users relinquish the use of their data for ‘data analysis, testing, [and] research.’” But once a study is under an IRB’s jurisdiction, the IRB is obligated to apply the standards of informed consent set out in the federal regulations , which go well, well beyond a one-time click-through consent to unspecified “research.” Facebook’s own terms of service are simply not relevant. Not directly, anyway.

>Facebook’s own terms of service are simply not relevant. Not directly, anyway.

According to Prof. Fiske’s now-uncertain report of her conversation with the authors, by contrast, the local IRB approved the study “on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.” This fact actually is relevant to a proper application of the Common Rule to the study.

Here’s how. Section 46.116(d) of the regulations provides:

An IRB may approve a consent procedure which does not include, or which alters, some or all of the elements of informed consent set forth in this section, or waive the requirements to obtain informed consent provided the IRB finds and documents that: 1. The research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects; 2. The waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects; 3. The research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration; and 4. Whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.

The Common Rule defines “minimal risk” to mean “that the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life.” The IRB might plausibly have decided that since the subjects’ environments, like those of all Facebook users, are constantly being manipulated by Facebook, the study’s risks were no greater than what the subjects experience in daily life as regular Facebook users, and so the study posed no more than “minimal risk” to them.

That strikes me as a winning argument, unless there’s something about this manipulation of users’ News Feeds that was significantly riskier than other Facebook manipulations. It’s hard to say, since we don’t know all the ways the company adjusts its algorithms---or the effects of most of these unpublicized manipulations.

Even if you don’t buy that Facebook regularly manipulates users’ emotions (and recall, again, that it’s not clear that the experiment in fact did alter users’ emotions), other actors intentionally manipulate our emotions every day. Consider “ fear appeals ”---ads and other messages intended to shape the recipient’s behavior by making her feel a negative emotion (usually fear, but also sadness or distress). Examples include “scared straight” programs for youth warning of the dangers of alcohol, smoking, and drugs, and singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan’s ASPCA animal cruelty donation appeal (which I cannot watch without becoming upset—YMMV--and there’s no way on earth I’m being dragged to the “ emotional manipulation ” that is, according to one critic, The Fault in Our Stars).

Continuing with the rest of the § 46.116(d) criteria, the IRB might also plausibly have found that participating in the study without Common Rule-type informed consent would not “adversely effect the rights and welfare of the subjects,” since Facebook has limited users’ rights by requiring them to agree that their information may be used “for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.”

__Finally, the study couldn’t feasibly have been conducted with full Common Rule-style informed consent--which requires a statement of the purpose of the research and the specific risks that are foreseen--without biasing the entire study. __Of course, surely the IRB, without biasing the study, could have required researchers to provide subjects with some information about this specific study beyond the single word “research” that appears in the general Data Use Policy, as well as the opportunity to decline to participate in this particular study, and these things should have been required on a plain reading of § 46.116(d).

In other words, the study was probably eligible for “alteration” in some of the elements of informed consent otherwise required by the regulations, but not for a blanket waiver.

Moreover, subjects should have been debriefed by Facebook and the other researchers, not left to read media accounts of the study and wonder whether they were among the randomly-selected subjects studied.

Still, the bottom line is that---assuming the experiment required IRB approval at all---it was probably approvable in some form that involved much less than 100 percent disclosure about exactly what Facebook planned to do and why.

There are (at least) two ways of thinking about this feedback loop between the risks we encounter in daily life and what counts as “minimal risk” research for purposes of the federal regulations.

One view is that once upon a time, the primary sources of emotional manipulation in a person’s life were called “toxic people,” and once you figured out who those people were, you would avoid them as much as possible. Now, everyone’s trying to nudge, data mine, or manipulate you into doing or feeling or not doing or not feeling something, and they have access to you 24/7 through targeted ads, sophisticated algorithms, and so on, and the ubiquity is being further used against us by watering down human subjects research protections.

There’s something to that lament.

The other view is that this bootstrapping is entirely appropriate. If Facebook had acted on its own, it could have tweaked its algorithms to cause more or fewer positive posts in users’ News Feeds even *without *obtaining users’ click-through consent (it’s not as if Facebook promises its users that it will feed them their friends’ status updates in any particular way), and certainly without going through the IRB approval process. It’s only once someone tries to learn something about the effects of that activity and share that knowledge with the world that we throw up obstacles.

>Would we have ever known the extent to which Facebook manipulates its News Feed algorithms had Facebook not collaborated with academics incentivized to publish their findings?

Academic researchers’ status as academics already makes it more burdensome for them to engage in exactly the same kinds of studies that corporations like Facebook can engage in at will. If, on top of that, IRBs didn’t recognize our society’s shifting expectations of privacy (and manipulation) and incorporate those evolving expectations into their minimal risk analysis, that would make academic research still harder, and would only serve to help ensure that those who are most likely to study the effects of a manipulative practice and share those results with the rest of us have reduced incentives to do so. Would we have ever known the extent to which Facebook manipulates its News Feed algorithms had Facebook not collaborated with academics incentivized to publish their findings?

We can certainly have a conversation about the appropriateness of Facebook-like manipulations, data mining, and other 21st-century practices. But so long as we allow private entities to engage freely in these practices, we ought not unduly restrain academics trying to determine their effects. Recall those fear appeals I mentioned above. As one social psychology doctoral candidate noted on Twitter, IRBs make it impossible to study the effects of appeals that carry the same intensity of fear as real-world appeals to which people are exposed routinely, and on a mass scale, with unknown consequences. That doesn’t make a lot of sense. What corporations can do at will to serve their bottom line, and non-profits can do to serve their cause, we shouldn’t make (even) harder---or impossible---for those seeking to produce generalizable knowledge to do

- This post originally appeared on The Faculty Lounge under the headline How an IRB Could Have Legitimately Approved the Facebook Experiment—and Why that May Be a Good Thing .*

The Hastings Center

Bioethics Forum Essay

Facebook’s emotion experiment: implications for research ethics.

Several aspects of a recently published experiment conducted by Facebook have received wide media attention, but the study also raises issues of significance for the ethical review of research more generally. In 2012, Facebook entered almost 700,000 users – without their knowledge – in a study of “massive-scale emotional contagion.” Researchers manipulated these individuals’ newsfeeds by decreasing positive or negative emotional content, and then examined the emotions expressed in posts. Readers’ moods were affected by the manipulation. Of the three authors, two worked at Cornell University at the time of the research; all three are social scientists.

The study raises several critical questions. Did it violate ethical standards of research? Should such social media company studies be reviewed differently than at present? Did the journal publishing the study proceed appropriately?

Federal regulations concerning the conduct of research technically apply only to certain categories of government-funded research and follow ethical principles closely paralleling those of the Helsinki Declaration. Requirements include prospective review by an institutional review board (IRB) and (with some exceptions) subjects’ informed consent. Institutions conducting federally-funded research indicate whether they will apply these guidelines to all research they conduct. These guidelines have become widely-used ethical standards.

Was Facebook obligated to follow these ethical guidelines, since the study was privately funded? At the very least, it seems that the behavioral scientists involved should have followed them, since doing so is part of the professional code of conduct of their field.

The absence of consent is a major concern. Facebook initially said that the subjects consented to research when signing up for Facebook; but in fact the company altered its data use agreement only four months after the study to include the possibility of research. Even if research had been mentioned, as it is now, it is doubtful that would have met widely accepted standards. This statement now says, “we may use the information we receive about you . . . for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement . . .” Not only do most users of online services fail to read such use agreements (perhaps not unreasonably), but mere mention of the possibility of research provides users with no meaningful information about the experiment’s nature.

Regulations stipulate that researchers must respect subjects’ rights, and describe for participants the study’s purposes, procedures, and “foreseeable risks or discomforts.” IRBs can waive informed consent in certain instances, if the subjects’ “rights and wellbeing” will not be compromised. The regulations permit such waiver only for minimal risk research – where risks are “not greater . . . than those ordinarily encountered in daily life.” One could argue that having newsfeeds manipulated is part of the “daily life” of users, because Facebook regularly does so anyway. That argument seems dubious. While the company may regularly focus newsfeeds on content of interest to the user, not all manipulations are the same. Here, the goal was to alter the user’s mood, a particularly intrusive intervention, outside the expected scope of behavior by a social media company.

Did the study otherwise involve more than minimal risk? Seeking to alter mood is arguably less benign than simply ascertaining what type of music users prefer. Altered mood can affect alcohol and drug use, appetite, concentration, school and work performance and suicidality. It is not clear that this experiment altered mood to that degree. However, we do not know how far Facebook or other social media companies have gone in other experiments attempting to alter users’ moods or behavior.

The study also appears to have included children and adolescents, raising other concerns. Their greater vulnerability to manipulation and harm has led to special provisions in the federal regulations, limiting the degree of risk to which they are exposed, and requiring parental consent – not obtained by Facebook. The company could easily have excluded minors from the study – since users all provide their age – but apparently didn’t do so.

Susan Fiske, who edited the article for PNAS , has stated , “The authors indicated that their university IRB had approved the study, on the grounds…[of] the user agreement.” The authors told the journal that Facebook conducted the study “ for internal purposes .” Cornell’s IRB decided that its researchers were “not directly engaged” in human subject research, since they had no direct contact with subjects, and that no review was necessary. But federal guidance stipulates that if institutions decide that investigators are not involved, “it is important to note that at least one institution must be determined to be engaged,” so that some IRB review takes place. There is no evidence that any other IRB or equivalent review occurred – highlighting needs for heightened IRB diligence about this obligation.

PNAS has since published an “Editorial Expression of Concern” that the study “. . . may have involved practices that were not fully consistent with the principles of obtaining informed consent . . .” PNAS requires all studies to follow the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, which mandates as well that subjects be informed of the study’s “aims, methods . . . and the discomfort it may entail.” Many journals request that authors inform them about IRB review; however, one lesson from the Facebook study is that journals should ask for copies of the IRB approval. Journals should also require authors to state in the published article whether IRB approval was obtained – information often not reported– so that readers can assess these issues as well.

Scientific research, which can benefit society in manifold ways, requires public trust. Research that sparks widespread public outcry – as this study has – can undermine the scientific enterprise as a whole.

Social media companies should follow accepted ethical standards for research. Such adherence does not need to be very burdensome. Companies could simply submit their protocols to a respected independent IRB for assessment. (The objectivity of an in-house IRB, most of whose members are employees, may be questionable.) Facebook should also exclude children and adolescents from experiments that seek to manipulate subjects’ moods.

Alternatively, governments could mandate that social media and other companies follow these ethical guidelines. But public policies can have unforeseen consequences. As a first step, requesting that companies voluntarily follow these guidelines might go a long way toward improving the current situation.

Robert Klitzman is professor of psychiatry and director of the Masters of Bioethics Program at Columbia University. Paul S. Appelbaum is the Elizabeth K Dollard Professor, Columbia University Medical Center and New York State Psychiatric Institute. Both are Hastings Center Fellows.

Acknowledgements: Funding for this study was provided by P50 HG007257 (Dr. Paul S. Appelbaum, PI). The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors would like to thank Patricia Contino and Jennifer Teitcher for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Posted by Susan Gilbert at 07/21/2014 03:59:38 PM |

Hastings Bioethics Forum essays are the opinions of the authors, not of The Hastings Center.

Recent Content

Ethical Considerations for Using AI to Predict Suicide Risk

Now What? Bioethics and Mitigating Climate Disasters

Benjamin Cardozo on Medicine and the Law: Wisdom for Senate Confirmation Hearings

What 23andMe Owes its Users

After the Election, Our Aging Society Will Still Need Care Policy

Do Your Part to Address Climate Change: Vote

The Reactionary Recommendations of Project 2025: Why Bioethicists Should Care

When Bioethics is Like Surfing: Changing Federal Policy

The Alarming History Behind Trump’s “Bad Genes” Comments

Say Their Names: Unclaimed Bodies and Untrustworthiness in Medical Science

Breaking Boundaries: Reframing Clinical Ethics Discussions of Health Care for Incarcerated Patients

Priced Out of Publishing in Bioethics Journals

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not The Hastings Center.

- What Is Bioethics?

- For the Media

- Hastings Center News

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Hastings Center Report

- Hastings Bioethics Resources

- Ethics & Human Research

- Focus Areas

- Hastings Bioethics Forum

- Bioethics Careers & Education

- Bioethics Briefings

- Books by Hastings Scholars

- Special Reports

- Online Giving

- Ways To Give

- The Hastings Center Beneficence Society

- Why We Give

- Gift Planning

- Twitter / X

Upcoming Events

Previous events, receive our newsletter.

- Terms of Use

The Ethics and Society Blog

Ethical analysis & news from the fordham university center for ethics education, issues of research ethics in the facebook ‘mood manipulation’ study: the importance of multiple perspectives.

By: Michelle Broaddus, Ph.D.

A new study using Facebook data to study “emotional contagion,” and the ensuing backlash of its publication offers the opportunity to examine several ethical principles in research. One of the pillars of ethically conducted research is balancing the risks to the individual participants against the potential benefits to society or scientific knowledge. While the study’s effects were quite small, the authors argue that “given the massive scale of social networks such as Facebook, even small effects can have large aggregated consequences.” However, participants were not allowed to give informed consent, which constitutes a risk of the research and the major source of the backlash.

The ethical issues are complicated by the lack of federal funding, and associated lack of required compliance with federal regulations, the rights of private companies to adjust their services, the fact that this research could conceivably still have ethically been conducted with a waiver of consent, and the possible ethical obligation that powerful private companies might have to contributing to scientific knowledge and not just financial gain. Reporting on the study has also often used inflammatory and misleading language, which has ethical implications as well. Issues of research ethics should involve constant questioning and discussions, especially as research evolves in response to extremely rapidly changing technologies. As this study and its associated backlash have demonstrated, these discussions should involve perspectives from participants, researchers, editors, reviewers, and science journalists.

For a more in-depth discussion of the ethical issues raised in the Facebook study, please read the full text of Broaddus’ piece .

Michelle Broaddus holds a Ph.D. in Social Psychology, and is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Medicine. She completed a two-year fellowship with the Fordham University HIV and Drug Abuse Prevention Research Ethics Training Institute . The views expressed are her own and do not necessarily represent the views of her institution, Fordham University, the Research Ethics Training Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the United States Government.

The author wishes to thank Jennifer Kubota, Ph.D., for her feedback on an original draft of this post.

Share this:

One comment.

[…] Issues of Research Ethics in the Facebook ‘Mood Manipulation’ Study: The Importance of Multiple … was originally published @ Ethics and Society and has been syndicated with permission. […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Consent and ethics in Facebook’s emotional manipulation study

Associate Professor of Medical Ethics, Flinders University

Disclosure statement

David Hunter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Significant concerns are raised about the ethics of research carried out by Facebook after it revealed how it manipulated the news feed of thousands of users.

In 2012 the social media giant conducted a study on 689,003 users, without their knowledge, to see how they posted if it systematically removed either some positive or some negative posts by others from their news feed over a single week.

At first Facebook’s representatives seemed quite blasé about anger over the study and saw it primarily as an issue about data privacy which it considered was well handled.

“There is no unnecessary collection of people’s data in connection with these research initiatives and all data is stored securely,” a Facebook spokesperson said.

In the paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science , the authors say they had “informed consent” to carry our the research as it was consistent with Facebook’s Data Use Policy, which all users agree to when creating an account.

One of the authors has this week defended the study process, although he did apologise for any upset it caused, saying: “In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.”

Why all the outrage?

So why are Facebook, the researchers and those raising concerns in academia and the news media so far apart in their opinions?

Is this just standard questionable corporate ethics in practice or is there a significant ethical issue here?

I think the source of the disagreement really is about the consent (or lack thereof) in the study and as such will disentangle what concerns about consent there are and why they matter.

There are two main things that would normally be taken as needing consent in this study:

- accessing the data

- manipulating the news feed.

Accessing the data

This is what the researchers and Facebook focussed on. They claimed that agreeing to Facebook’s Data Use Policy when you sign up to Facebook constitutes informed consent. Let’s examine that claim.

We use the information we receive about you […] for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.

It’s worth noting that this in no way constitutes informed consent since it’s unlikely that all users have read it thoroughly. While it informs you that your data may be used, it doesn’t tell you how it will be used.

But given that the data has been provided to the researchers in an appropriately anonymised format, the data is no longer personal and hence that this mere consent is probably sufficient.

It’s similar to practices in other areas such as health practice audits which are conducted with similar mere consent.

So insofar as Facebook and the researchers are focusing on data privacy, they are right. There is nothing significant to be concerned about here, barring the misdescription of the process as “informed consent”.

Manipulating the news feed

This was not a merely observational study but instead contained an intervention – manipulating the content of users’ news feed.

Informed consent is likewise lacking for this intervention, placing this clearly into the realm of interventional research without consent.

This is not say it is necessarily unethical, since we sometimes permit such research on the grounds that the worthwhile research aims cannot be achieved any other way.

Nonetheless there are a number of standards that research without consent is expected to meet before it can proceed:

1. Lack of consent must be necessary for the research

Could this research be done another way? It could be argued that this could have been done in a purely observational fashion by simply picking out users whose news feed were naturally more positive or negative.

Others might say that this would introduce confounding factors, reducing the validity of the study.

Let’s accept that it would have been challenging to do this any other way.

2. Must be no more than minimal risk

It’s difficult to know what risk the study posed – judging by the relatively small effect size probably little, but we have to be cautious reading this off the reported data for two reasons.

First, the data is simply what people have posted to Facebook which only indirectly measures the impact – really significant effects such as someone committing suicide wouldn’t be captured by this.

And second, we must look at this from the perspective of before the study is conducted where we don’t know the outcomes.

Still for most participants the risks were probably minimal, particularly when we take into account that their news feed may have naturally had more or less negative/positive posts in any given week.

3. Must have a likely positive balance of benefits over harms

While the harms caused directly by the study were probably minimal the sheer number of participants means on aggregate these can be quite significant.

Likewise, given the number of participants, unlikely but highly significant bad events may have occurred, such as the negative news feed being the last straw for someone’s marriage.

This will, of course, be somewhat balanced out by the positive effects of the study for participants which likewise aggregate.

What we further need to know is what other benefits the research may have been intended to have. This is unclear, though we know Facebook has an interest in improving its news feed which is presumably commercially beneficial.

We probably don’t have enough information to make a judgement about whether the benefits outweigh the risks of the research and the disrespect of subjects’ autonomy that it entails. I admit to being doubtful.

4. Debriefing & opportunity to opt out

Typically in this sort of research there ought to be a debriefing once the research is complete, explaining what has been done, why and giving the participants an option to opt out.

This clearly wasn’t done. While this is sometimes justified on the grounds of the difficulty of doing so, in this case Facebook itself would seem to have the ideal social media platform that could have facilitated this.

The rights and wrongs

So Facebook and the researchers were right to think that in regards to data access the study is ethically robust. But the academics and news media raising concerns about the study are also correct – there are significant ethical failings here regarding our norms of interventional research without consent.

Facebook claims in its Data Usage Policy that: “Your trust is important to us.”

If this is the case, they need to recognise the faults in how they conducted this study, and I’d strongly recommend that they seek advice from ethicists on how to make their approval processes more robust for future research.

- Social media

- Research ethics

- Data privacy

Research Analyst and Writer

Research Assistant

Lecturer in Dementia Studies

Research Officer/Senior Research Officer

Head of IT Operations

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Consider Fiske's explanation of the research ethics here—the study was approved "on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people's News Feeds all the time."

Facebook conducted a study for one week in 2012 testing the effects of manipulating News Feed based on emotions. The results have hit the media like a bomb. What did the study find? Was it ethical ...

The Facebook study, entitled Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks (Kramer et al., 2014), was a collaborative endeavour between Facebook and Cornell University's Departments of Communication and Information Science.In it, Facebook researchers directly manipulated Facebook users' news feeds to display differing amounts of positive and negative ...

A recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences describes a mood manipulation experiment conducted by Facebook scientists during one week in 2012 that suggests evidence of "emotional contagion," or the spread of positive and negative affect between people. The backlash to this publication has been significant.

Several aspects of a recently published experiment conducted by Facebook have received wide media attention, but the study also raises issues of significance for the ethical review of research more generally. In 2012, Facebook entered almost 700,000 users - without their knowledge - in a study of "massive-scale emotional contagion."

By: Michelle Broaddus, Ph.D. A new study using Facebook data to study "emotional contagion," and the ensuing backlash of its publication offers the opportunity to examine several ethical principles in research. One of the pillars of ethically conducted research is balancing the risks to the individual participants against the potential benefits to society or…

Mary Gray et al., MSR Faculty Summit 2014 Ethics Panel Recap (transcript of July 14 panel discussing Internet research ethics post-Facebook experiment) James Grimmelmann, As Flies to Wanton Boys (The Laboratorium, ... Michael Hiltzik, Facebook on its mood manipulation study: Another non-apology apology (Los Angeles Times, July 2, 2014)

Facebook emotional manipulation experiment. ... The leader of the experiment Adam D. I. Kramer, apologized for the experiment and suggested that the results were insignificant and not worth the anxiety that the reports of the experiment. [4] References This page was last edited on ...

Significant concerns are raised about the ethics of research carried out by Facebook after it revealed how it manipulated the news feed of thousands of users. In 2012 the social media giant ...

The Facebook Experiment as Manipulation On Facebook, the News Feed is practically a list of sta- tus updates of the contacts in a user's network.