Choice Blindness: Do You Notice If You Get What You Choose?

Choice blindness is widespread..

Posted August 14, 2023 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- People sometimes don’t notice that they get what they did not choose.

- Experiments indicate that our free will may in face be limited.

- We think our preferences affect our choices; often, however, our choices affect our preferences.

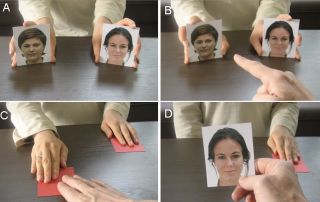

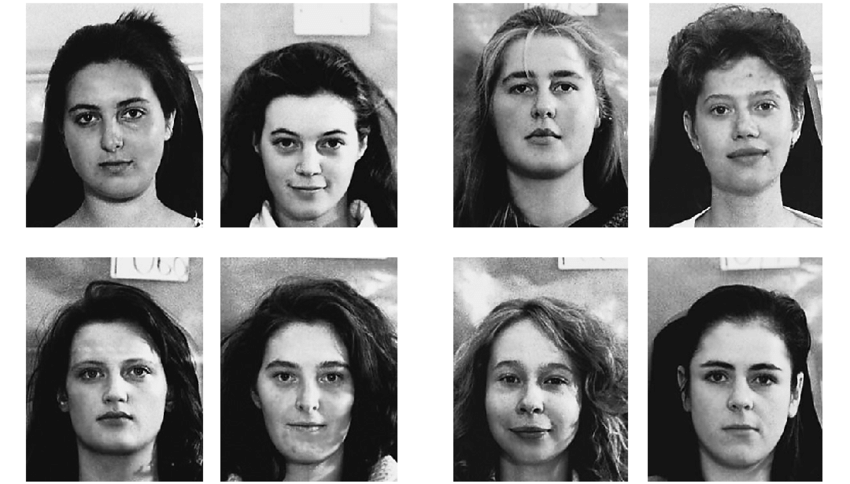

Imagine that you take part in the following experiment: An experimenter presents two black-and-white photos of young women and asks you to point at the one you find most attractive. You look at the pictures and point to the one you find most appealing.

The experimenter then places the photos face down on the table and slides the card you selected toward you. As you pick up the photo, you are now asked to explain why you chose the woman in the image.

Do you think you would notice if the photo you pick up is not the one you chose?

You're probably confident that you would. But it's most likely that you would not.

This experiment was conducted by cognitive scientists Petter Johansson and Lars Hall and their colleagues at Lund University. The pivotal point is that in certain instances, the card received by the subject is switched—utilizing a simple magic trick involving double cards—so that the picture to be justified is the one that was not initially chosen.

The astonishing outcome is that approximately 90 percent of the subjects failed to notice the substitution, even though the women in the pictures look very different. Moreover, subjects did not hesitate to justify why the woman depicted in the card they hold was most attractive, even if it was the other woman they originally chose. Scientists have termed this phenomenon “choice blindness."

A series of experiments by the same group has revealed that choice blindness occurs in various contexts: For example, it takes place in a supermarket when choosing between two jams that you are offered to taste. Despite significant differences between the jams, most customers still do not notice that the jam they taste a second time is the one they did not initially choose. Again, they happily explain why they chose that jam.

One of the most thought-provoking experiments pertains to how easily we can be swayed to change our political opinion. A few weeks before the 2010 parliamentary election in Sweden, a number of people were surveyed on the street about their intended party vote. They were then asked to fill in a form indicating their stance on 12 political issues of the day, using a “agree/do not agree” scale, such as tax rates and nuclear power.

Unbeknownst to the subjects, the experimenter secretly filled in another form, which was then swapped with the original one without the subject noticing. In this new form, some of the responses were changed on the scale to be on the other side of the party bloc boundary , compared to what the subject had originally responded. Subjects were then asked to give their reasons for marking the questions where the answers had been manipulated.

Very few discovered that any of the answers had been changed (92 percent accepted the manipulated form as their own). Surprisingly, for 48 percent of the subjects, their answers indicated a shift toward supporting the opposing party due to the manipulation, compared to what they had originally indicated. This figure is significantly higher than the 10 percent that political scientists and politicians usually think can be influenced before an election.

When the trick was revealed to the subjects, many admitted they were not as ideologically committed as they had thought. Conversely, many were relieved that they had not actually switched sides, saying, "Phew, I'm not a conservative after all!"

You think you choose what you prefer. But sometimes you prefer what you choose. To prove it, all you have to do is pull out photos of yourself from a decade ago. The hairstyle and clothing you wore at that time seemed like your personal choices. However, in hindsight, you realize how much you were influenced by the fashion trend of the time, and that the choices you made were heavily influenced by social norms.

It can be demonstrated that your choices also affect your preferences: In a follow-up to the photo selection experiment involving women, subjects were asked to choose between the same pair of faces at a later date. Remarkably, for those pairs where subjects were given the photo that they had originally not chosen, they now selected that photo significantly more often. In other words, the mere belief they had previously chosen the other woman made them choose her on the later occasion.

The experiments presented here pose major problems for those who assert that humans have completely free will. What we perceive as free choice is in many cases dictated by mechanisms of which we are unaware, and perhaps cannot even become aware of. Our perception of free will may largely be an illusion. It is even uncertain if a "self" governs our actions. In fact, the choice blindness experiments show that we rely more on what we see with our eyes than what we were thinking when we made the choice.

Johansson, P., Hall, L., Sikström, S. & Olsson, A. (2005): Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task, Science 310, 116-119.

Hall, L., Johansson, P., Tärning, B., Sikström, S., & Deutgen, T. (2010). Magic at the marketplace: Choice blindness for the taste of jam and the smell of tea. Cognition , 117 (1), 54-61.

Hall, L. Johansson, P. & Strandberg, T. (2012): Lifting the veil of morality: Choice blindness and attitude reversals on a self-transforming survey, PLoS One 7 , e45457.

https://www.ted.com/talks/petter_johansson_do_you_really_know_why_you_do_what_you_do

Peter Gärdenfors, Ph.D. , is a professor of cognitive science at Lund University, Sweden.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

There’s been a fundamental shift in how we define adulthood—and at what pace it occurs. PT’s authors consider how a once iron-clad construct is now up for grabs—and what it means for young people’s mental health today.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Explore Psychology

What Is Choice Blindness? Definition and Examples

Choice blindness is a psychological phenomenon in which people fail to notice a mismatch between their intended choice and the choice presented to them. In other words, it is a surprising tendency to be unaware that our choices and preferences have been changed or manipulated after we’ve already made a choice. This tendency suggests that…

Choice blindness is a psychological phenomenon in which people fail to notice a mismatch between their intended choice and the choice presented to them. In other words, it is a surprising tendency to be unaware that our choices and preferences have been changed or manipulated after we’ve already made a choice.

This tendency suggests that even if we don’t get the thing we actually chose, there are many times we won’t even notice. For example, if you order something at a restaurant and get something slightly different, you might not notice the discrepancy.

In this article

Definition of Choice Blindness

One definition suggests that:

“Choice blindness happens when people fail to notice mismatches between their intentions and the consequences of decisions” (Lachaud, Jacquet, & Baratgin, 2022).

Choice blindness is a form of introspection illusion. Essentially, this illusion suggests that we have direct insight into the origins of our mental states. We treat our own introspections as absolute truth while also discounting other people’s introspections as mistaken or unreliable.

So when you order a turkey sandwich at your local delicatessen but get a ham sandwich instead, you’ll either not notice the mistake or invent reasons why the ham sandwich was what you actually wanted in the first place.

Choice blindness underscores how factors like unconscious decision-making, memory distortions, and perceptual errors affect our decision-making. It also provides insight into our own self-awareness regarding the choices that we make.

The Psychology of Choice

The psychology of choice seeks to understand how people make decisions when asked to choose between two or more options. While we might like to think that each decision is something carefully made using rationality and logic, there are actually a whole host of influences that play a role, many of which can be quite irrational.

Conscious influences play a part, but so can unconscious forces. Our memories, past experiences , and cognitive biases also affect our choices.

Even subtle factors like priming can impact the decisions we make. Priming happens when exposure to one stimulus influences how we respond to a subsequent stimulus.

Biases also affect decisions. Some common types of bias that impact choices include the anchoring bias , confirmation bias, and ingroup bias .

Even the number of options we have to choose from can affect our decision. To few choices means we might miss out on good options, but too many choices can leave us feeling overwhelmed and indecisive.

Research on Choice Blindness

The experiments on choice blindness, often associated with the work of researchers Johansson, Hall, Sikstrom, and Olsson, involve a set of studies designed to investigate the phenomenon and its underlying mechanisms. One notable experiment typically follows these key elements:

The Experiment

Participants are presented with a choice between two options. In one case, this involved choosing between two different female faces. After making their selection, the participants are then handed the chosen item, which is visually different from what they initially selected. For instance, if they chose face A, they might be given face B.

Manipulation and Misdirection

The critical aspect of the experiment involves introducing a form of misdirection or manipulation. Participants are engaged in a conversation or distraction immediately after making their choice, diverting their attention away from the actual switch of the chosen item.

The misdirection is crucial to ensure that participants remain unaware of the mismatch between their intended choice and the received item.

Revealing the Discrepancy

Following the distraction phase, participants are asked to explain or justify their choice. During this process, researchers reveal the switch by showing the participants what they actually received.

Surprisingly, many participants fail to notice the discrepancy and may offer explanations for a choice they did not make. In one study, just 13% of the participants actually noticed that the image they received did not match the one they had chosen.

Analysis and Implications

Researchers analyze the responses to understand the extent of choice blindness and the factors influencing it. The findings shed light on the malleability of our awareness regarding decision outcomes, emphasizing the role of cognitive processes, memory, and external influences.

The experiments not only provide empirical evidence for choice blindness but also offer insights into the limitations of introspection and self-awareness in understanding our own choices.

In other variations of the experiments, researchers have demonstrated they could produce the same effects with food and political candidates.

These experiments showcase how individuals can be blind to the discrepancies between their intended choices and the outcomes, illustrating the complexity of decision-making processes and the surprising gaps in our awareness.

Causes of Choice Blindness

Choice blindness is influenced by a number of causes. Decision-making is a complex process that involves numerous processes and has many influences. No wonder we aren’t always aware of all of the factors that play a role in affecting our choices. Some key causes include:

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are errors in thinking. Many different cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias and choice-supportive bias, can contribute to choice blindness. These biases shape our interpretation and memory of choices, leading individuals to overlook inconsistencies between their intended choices and the presented outcomes.

What we are paying attention to while choosing can also play a major role in choice blindness. If your attention is diverted by something else, you won’t analyze your choices as much. Because your attention is distracted, you’re less likely to notice if the option presented doesn’t match your original selection.

Memory Distortion

Memory is not a perfect record of our experiences. Choice blindness experiments reveal how memory distortion can occur. People often find ways to justify the mismatch, even inventing explanations for why they chose what they did. This memory distortion further obscures the awareness of the choice-outcome mismatch.

Perceptual Errors

Humans may experience perceptual errors in recognizing visual or sensory differences between the chosen and received items. The brain might fill in gaps or overlook inconsistencies, especially if the differences are subtle. This contributes to individuals failing to notice the mismatch between their intended choices and the presented outcomes.

Environmental Factors

External factors, including social pressure or the experimental context, can influence decision-making and contribute to choice blindness. People often align their explanations with social expectations or context cues, further obscuring their awareness of the actual outcomes.

Cognitive Dissonance

When faced with a choice-outcome discrepancy, individuals may experience cognitive dissonance , a psychological discomfort resulting from conflicting beliefs or attitudes. To resolve this discomfort, individuals might unconsciously alter their perception of the initial choice to align with the received outcome.

Examples of Choice Blindness

Choice blindness can manifest in various everyday situations, demonstrating how individuals may fail to recognize discrepancies between their intended choices and the outcomes. Here are some common examples:

Menu Choices

Imagine ordering a specific dish at a restaurant and receiving a visually similar but different item. If the waiter presents it confidently and you’re engaged in conversation, you may not immediately notice the switch. Later, when asked about your choice, you might explain the dish you thought you ordered.

Shopping Selections

When shopping, especially online, you may choose a particular product based on its features or appearance. However, due to packaging similarities or mislabeling, you might receive a different variant or brand.

Choice blindness may make you rationalize the received item as the one you initially intended to purchase.

Clothing Preferences

While shopping for clothes, you may select an outfit but then get distracted chatting with friends or checking on your phone. If the cashier hands you a slightly different garment, you might not even notice that it isn’t what you originally picked out.

In this scenario, you might fail to notice the substitution and later explain why they chose the received clothing item.

Survey Responses

Participants in surveys or interviews may provide answers that align with social expectations or perceived norms, even if those responses differ from their true preferences. This aligns with choice blindness, where individuals unknowingly offer justifications for choices they did not make.

Product Customization

Imagine that you are customizing a product online where you select specific features, colors, or options. However, the final product may differ due to technical glitches or user interface issues.

Choice blindness might make you unaware of the discrepancy when receiving the product, and you might even try to find ways to rationalize your choices during post-purchase questioning.

Political Preferences

In politics, individuals might express support for a particular policy or candidate but fail to notice changes to their stated preferences. This could happen in surveys or discussions where external influences subtly alter their responses. This means that their stated choices and actual preferences don’t align.

How to Overcome Choice Blindness

Overcoming choice blindness involves developing awareness, critical thinking, and mindfulness in decision-making processes. Here are some strategies that individuals can use to help reduce the effects of choice blindness:

Slow Down and Reflect

Take the time to slow down and reflect on your choices. Avoid making decisions hastily, especially in situations where distractions are present. Creating a mental pause before confirming a choice allows for better self-awareness and reduces the likelihood of overlooking discrepancies.

Increased Attention to Details

Pay close attention to the details of your choices and the outcomes. Be vigilant in observing visual or sensory differences between the selected option and the received item. Training yourself to notice subtleties can enhance your ability to catch inconsistencies.

Double-Check Choices

Develop a habit of double-checking your choices, especially when misdirection or distractions are likely. Verifying your decisions before moving forward can help ensure that your perceived choices align with your actual intentions.

Mindful Decision-Making

Practice mindful decision-making by being fully present in the moment when making choices. Minimize external distractions and focus on the task at hand.

Mindfulness enhances your awareness of the decision-making process, reducing the chances of falling victim to choice blindness.

Question Your Choices

Regularly question and examine your choices, motivations, and preferences. By engaging in self-reflection, you can identify potential biases, social influences, or cognitive factors that may impact your decisions. Actively challenging your own thought processes contributes to greater self-awareness.

Seek Feedback from Others

When possible, seek feedback from others about your choices. External perspectives can provide valuable insights and highlight potential discrepancies. Discussing decisions with friends, colleagues, or mentors adds an external layer of awareness to your choices.

Educate Yourself on Cognitive Biases

Familiarize yourself with common cognitive biases that influence decision-making. Understanding biases such as confirmation bias or choice-supportive bias can empower you to recognize and counteract their effects on your perceptions of choices.

Keep a Decision-Making Journal

Maintain a journal where you record your decisions, reasons for making them, and the outcomes. Periodically reviewing this journal allows you to track patterns, identify any discrepancies, and gain a deeper understanding of your decision-making tendencies.

By incorporating these strategies into their decision-making processes, you can enhance your ability to recognize and overcome choice blindness.

Key Points to Remember

- Choice blindness refers to the phenomenon where individuals are unaware of discrepancies between their intended choices and the outcomes they receive.

- It highlights the subconscious nature of decision-making, influenced by cognitive biases, distractions, and memory distortions.

- Everyday examples include ordering at a restaurant, online shopping, and expressing preferences in surveys.

- Strategies to overcome choice blindness include slowing down, paying attention to details, questioning choices, and seeking feedback from others.

Zhaoyang, R., & Martire, L. M. (2021). The influence of family and friend confidants on marital quality in older couples. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76 (2), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa029

Johansson, P., Hall, L., Sikström, S., & Olsson, A. (2005). Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task. Science, 310 (5745), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111709

Lachaud, L., Jacquet, B., & Baratgin, J. (2022). Reducing Choice-Blindness? An Experimental Study Comparing Experienced Meditators to Non-Meditators. European journal of investigation in health, psychology and education , 12 (11), 1607–1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12110113

Sagana, A., Sauerland, M., & Merckelbach, H. (2018). Warnings to Counter Choice Blindness for Identification Decisions: Warnings Offer an Advantage in Time but Not in Rate of Detection. Frontiers in psychology , 9 , 981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00981

Sagana, A., Sauerland, M., & Merckelbach, H. (2014). Memory impairment is not sufficient for choice blindness to occur. Frontiers in psychology , 5 , 449. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00449

Rieznik, A., Moscovich, L., Frieiro, A., Figini, J., Catalano, R., Garrido, J. M., Álvarez Heduan, F., Sigman, M., & Gonzalez, P. A. (2017). A massive experiment on choice blindness in political decisions: Confidence, confabulation, and unconscious detection of self-deception. PloS one , 12 (2), e0171108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171108

Explore Psychology covers psychology topics to help people better understand the human mind and behavior. Our team covers studies and trends in the modern world of psychology and well-being.

Related Articles:

Examples of the Serial Position Effect

The serial position effect refers to the tendency to be able to better recall the first and last items on a list than the middle items. Psychology Hermann Ebbinghaus noted during his research that his ability to remember the items on a list depended on the position of the item on the list. An example…

Cognitive Bias: Common Types and How to Avoid Them

A cognitive bias is an unconscious systematic pattern of thinking that can result in errors in judgment. These biases stem from the brain’s limited resources and need to simplify the world to make faster decisions. Such biases are often the result of limitations or problems in memory, attention, and information processing. While such biases often…

Examples of Confirmation Bias (and How to Overcome It)

Looking for information that confirms what you already believe? That’s the confirmation bias at work. Here’s why it happens and how it affects how we think.

Fundamental Attribution Error: Definition and Examples

The fundamental attribution error is a type of cognitive bias that leads people to overemphasize personality and underemphasize situational factors.

What Is Crystallized Intelligence? Definition and Examples

Crystallized intelligence is all about what you’ve learned. Here’s why the wisdom you’ve picked up along the way is so important.

What Is the Barnum Effect in Psychology?

The Barnum effect is a type of cognitive bias that involves a tendency to believe that vague, general personality descriptions apply specifically and uniquely to them. Horoscopes are a good example of this phenomenon. While each horoscope is general, generic, and can apply to virtually anyone, people often feel like their own horoscope is strangely…

Thinking and Intelligence

Psych in Real Life: Choice Blindness

Learning objectives.

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving, including choice blindness

Choice Blindness

Some choices are easy (“Do you want pepperoni or anchovies on your pizza?”) and some choices are hard (“Are you going to get Amazon Echo or Google Home?”), but most of us like to think that we “know our own mind”—that is, when we finally make a choice, we are clear about our decision. Research by psychologists in Sweden shows that this confidence in our own self-knowledge may not always be justified.

Choice blindness is the failure to recall a choice immediately after we have made that choice. If you go to an ice cream store, order a chocolate cone, and then accept a strawberry cone without noticing, that is choice blindness. If you go to an electronics store, select the new 55-inch Vizio television, and then fail to notice when they bring out (and expect you to pay for) the far more expensive 55-inch Sony television, that is choice blindness. If you order a burger and fries, and then don’t notice when soup-and-salad is placed in front of you, that is choice blindness.

As you have seen, Johannson, Hall, and their colleagues [1] found a method for inducing choice blindness in a laboratory setting, but they wanted to do more than simply demonstrate that people sometimes forget their choices. As psychological scientists, their goal is to explore an interesting phenomenon (i.e., choice blindness) to understand why it happens and to see if it tells us anything new about the way our minds work.

The Attraction Preference Experiment

You can learn the basics of the experiment conducted by Petter Johannson, Lars Hall and their colleagues by watching the following video [2] .

Johannson and Hall were curious to see how often people noticed that there was a mismatch between their choice and the picture they were told they had chosen. Here’s how the experiment worked. Imagine that you are sitting across a table from an experimenter, who is dressed in a long sleeved black shirt. He shows you a pair of pictures of head-and-shoulder shots of two males or two females. On each trial, you indicate which of the two people in the pictures you find more attractive. After you make your choice, the experimenter hands you the card you just pointed at and asks you to explain why you preferred this person.

Except that this didn’t always happen this way. Using a magician’s trick, on some trials, when the experimenter handed you the card, he actually handed you the card you did NOT choose.

You can view the transcript for “BBC Choice Blindness” here (opens in new window) .

The researchers tested 120 college students (70 female, 50 male). The pictures were all of women. As the video showed, they made their choice and then immediately explained the reasons for their preference. Only 13% of the switches were detected immediately. Approximately 10% more switches were mentioned “retrospectively”, where a participant initially justified choosing the switched face, but later indicated some suspicion that the wrong picture had been presented. Most participants who detected a switch attributed it to a technical error rather than suspecting that it was part of the research procedure.

But is it Real? The Value of Replication

The video you just watched described an experiment with a surprising result: more than 75% of the time, people make a choice and then, without indicating that anything is amiss, they proceed to justify a choice they did not make. But how solid is this study and how much can we believe these results? Maybe the choice blindness experiment reported real results, but (even assuming that the experimenters were completely honest and careful) could this have just been a weird outcome that will never happen again? In other words, is this a reliable result or just a fluke?

There is only one way to determine if a phenomenon is reliable, and that is replication . If you can’t replicate an effect, then you shouldn’t waste people’s time reading about it in a scientific paper.

There are at least three different types of replication.

- Direct Replication : Conduct exactly the same study again, usually with new participants from the same population as the original study. A successful replication would produce results similar to those in the original study.

- Systematic Replication : Conduct a study that is similar to the original one, but using slightly different methods or stimuli.

- Conceptual Replication : Conduct a very different study that still tests the original idea. In the current context, a conceptual replication would test the choice blindness idea using a method that did not involve choosing attractive people.

So, can you believe the choice blindness phenomenon?

In the years just before they published their 2005 study, the experimenters conducted two similar studies. For these studies, the pictures were presented on a computer screen, and the computer switched the pictures on the critical trials, so no magic was necessary. The results were very similar to the results of the study reported in the video above.

When the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) made the video, they reconstructed the experiment in a form very similar to the original. They reported that 80% of the participants did not notice any switching of pictures—a result very similar to the original. Unfortunately, without a published report of the study, it is impossible to know if the scientific standards of the original study had been maintained.

In 2014, researchers at the National University of Singapore reported a study similar to the experiment shown in the video. The stimuli were presented using a computer rather than a live experimenter. In addition to choosing one of the two faces, the participants rated their confidence in their choice and they typed their explanation of their preference. The faces were all of Caucasian women (as in the original study), but the participants were all of Asian descent (ethnic backgrounds: Chinese, Indian, and Vietnamese). Their results were similar to those of the original study.

Here is video showing another study by Johannson and Hall. The video has no sound—only subtitles.

You can view the transcript for “Using Choice Blindness to Shift Political Attitudes and Voter Intentions” here (opens in new window) .

Link to Learning

Visit this link to watch another video related about conceptual replication, this time related to taste.

From Phenomenon to Scientific Exploration

What you saw in the video is what a scientist would call a phenomenon—that is, a behavior that happens under certain conditions. The video showed that, if an experimenter is tricky enough, he or she can get people to justify choices that they never made. If you find this phenomenon interesting, then it may be worth your time to try to find out why it happens. (If you didn’t think it was interesting, then you will probably move on to find something that inspires you.)

Any of the choices in the list above could explain—fully or in part—the choice blindness phenomenon, but each idea would need to be tested. That is where the science comes in. The starting point for science is something interesting (a surprising phenomenon). If we are motivated to ask why something happened, then we jump into the real work of science: exploring possible explanations.

The next scientific step systematically (i.e., carefully and with specific purposes) changes elements of the procedures or stimuli to see how these changes affect the results. Remember that our dependent variable is the probability that the change in faces will be detected. So now we try to learn more about change blindness by seeing how changing specific details (independent variables) either increase or decrease people’s likelihood of noticing the switch in faces.

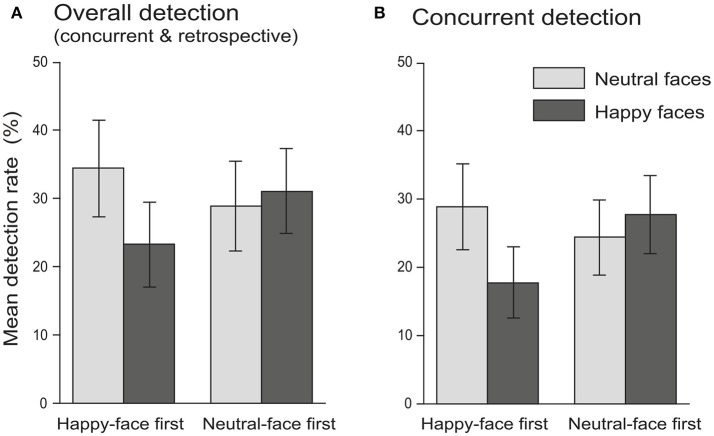

Two Variables: Time and Similarity

In the 2005 study, Johansson and Hall looked at two interesting variables that might influence detection of the mismatch. First, how rushed were the participants to make their decision? They gave some people only 2 seconds to choose the more attractive person. Others were given 5 seconds, and another group was given as long as people wanted (free choice). Should more time make someone more likely or less likely to notice that they have been given the picture they did not choose?

The second variable was how similar the two faces were to one another. In some cases, the two faces were similar to each other in general features, while in other cases the two faces were more distinctly different. If the two faces are quite different, how should that affect your ability to notice?

If we put the two manipulated variables (time and similarity) together, that gives us six conditions:

In the figure below, adjust the bars to fit your predictions about how often people would notice the picture switch. Higher bars mean people more often noticed that the cards had been switched. Lower bars mean that people made one choice and didn’t notice when they were given the wrong picture. This isn’t easy because you need to take account of the two variables: (1) amount of time looking at the pictures before your choice and (2) similarity of the faces in the pictures.

Most people make predictions that put the red bars lowest, the purple bars in the middle, and the green bars highest. This supports the idea that the more time you have to look at the pictures, the more likely you are to notice that the picture you have chosen is not the one the experimenter gave you.

People also expect that the switch will be more noticeable if the faces are dissimilar. For example, if we look at the green bars with unlimited time, it makes sense that people will generally notice when the faces have been switched on them, and this is much greater when the two faces are very different (dissimilar condition) than when they are similar (similar condition).

Most people find it hard to believe that lots of people will be tricked by the switch in faces, even if the experimenter has good magician skills. So, what did happen?

First, people generally did not notice the change in faces. Overall, participants on fewer than 20% of the trials noticed any of the card switches. Most participants simply did not realize that the faces had been switched, and many were either very surprised when they were told what had happened or they simply didn’t believe the experimenters.

There was an effect of time. The red bars (2 seconds to choose) are lower than the purple bars (5 seconds to choose), and the purple bars are lower than the green bars (unlimited time to choose), but the differences are fairly modest. The bigger surprise was the LACK of difference between the similar and dissimilar faces. In all three time conditions, there was no significant difference—barely a measurable difference–between the similar and dissimilar faces conditions. [3]

What Do These Results Tell Us?

With just these results, we are still a long way from understanding choice blindness. The experiment you just read takes us a couple of steps in the right direction. First, the similarity of the faces is (surprisingly) not a particularly influential factor. This does not mean that the case is closed and similarity is unimportant, but it does suggest that confusion due to similarity may not be the whole story.

The amount of time participants had to choose did have a big influence on detection of a switch in faces. When the participants were rushed (2 second condition), the chance of detecting a change was very slight. Given 5 seconds, detection improved, but not by a great amount. Unlimited time to choose made a substantial difference, but detection was still only around 25%. These results suggest that time to choose may be an important factor, but it is not the whole story. Furthermore, we are still not sure what it was about the extra time that led to improved detection. Did more time allow the participants to remember the faces better? Or perhaps their memory for faces was not improved, but they had more time to think of reasons they preferred one person over the other (her earrings, the way her hair flowed, a look in her eyes). These preferred features could signal to them that something was missing when the wrong picture was presented.

If you explore the research literature on choice blindness, you will find that the phenomenon has been studied from many angles. Experiments have been conducted in university laboratories and on the streets of a city in the Netherlands. Choice blindness in the video involved remembering what someone looked like, but choices involving sound, taste, and smell have also produced choice blindness. Even people’s judgments about their own personality and preferences is open to choice blindness. We don’t fully understand when and why choice blindness occurs, but it is an intriguing phenomenon, open to scientific curiosity.

A Final Thought

In a TED talk from 2016, Petter Johannson describes choice blindness to an audience. At the end he acknowledges that choice blindness can make people look silly or worse, but he also believes that this research provides us with an insight about people that may be reason for hope in a world seemingly full of discord and bereft of compromise.

Here are the closing lines from his TED talk:

This [choice blindness] may all seem a bit disturbing. But if you want to look at it from a positive direction, it could be seen as showing: Okay, so we’re all a little bit more flexible than we think. We can change our minds. Our attitudes are not set in stone. And we can also change the minds of others if we can only get them to engage with the issue and see it from the opposite view. … Getting rid of the need to stay consistent is actually a huge relief and makes [social] life so much easier to live. So the conclusion must be, “Know that you don’t know yourself. Or at least not as well as you think you do.”

CC licensed content, Original

- Psychology in Real Life: Choice Blindness. Authored by : Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Actors Headshots . Authored by : Vanity Studios. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/149481436@N03/34277183806/in/photostream/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/boy-portrait-outdoors-facial-men-s-3566903/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- man with beard. Authored by : Simon Robben. Provided by : Pexels. Located at : https://www.pexels.com/photo/face-facial-hair-fine-looking-guy-614810/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- image of businessman. Authored by : RoyalAnwar. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/model-businessman-corporate-2911332/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- man in black shirt. Authored by : songjayjay. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/face-men-s-asia-shirts-blacj-young-1391628/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- woman headshot. Authored by : Richard Ha. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/richardha101/31951459743/in/photolist-QFrzNX-V9Amf2-UM2ZU5-HMQxnd-WmpZx1-5ztiGT-ovm92d-28C1Eyi-qhwZzM-8szjMV-YRsM5B-LCTNFR-LtgVC9-LCUgd8-8gRLbQ-REArrY-WQNThG-ph52sx-2bC2DwH-qE61yp-28NspiC-21h8cj4-RVoBBc-29GiNJ3-21QEU6M-M1YTcp-PePwTJ-LALKtr-RVoBtg-Ry1bpy-FVr9BB-282GDDG-V7zSQJ-NwmdK9-29bSs5N-29mSb5G-272dN8p-26brtas-28tTQWf-RS1osg-WHoUSc-25uETMH-D7crwK-28m9fEh-25taZPB-JCwqE7-241e8Xp-265Ce4A-22V7VVo-25N7i4q . License : CC BY: Attribution

- businesswoman headshot. Authored by : Richard Rives. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/richpat2/38251159285/in/photostream/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

All rights reserved content

- BBC Choice Blindness. Authored by : BBC. Provided by : ChoiceBlindnessLab. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRqyw-EwgTk . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Using Choice Blindness to Shift Political Attitudes and Voter Intentions. Provided by : ChoiceBlindnessLab. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_htNx0eWmgs . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Petter Johannson, Lars Hall, Sverker Sikström, & Andreas Olsson. (2005). Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task. Science, 310 (7 October 2005), 116-119. ↵

- The video is a segment from a BBC video from the science series called Horizons. This particular show was about decision making ↵

- The results are more complex than the figure suggests. The data shown above are limited to first detections of the switch in pictures. After people notice that there has been a switch, they tend to be a bit suspicious and they are more vigilant about noticing changes. If all trials are taken into account, the data are still similar to these, but not quite as pretty. See the original paper for all the details. ↵

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

- Psychology >

Choice Blindness

Peter johansson's experiment, peter johansson's experiment.

Choice blindness refers to ways in which people are blind to their own choices and preferences. Lars Hall and Peter Johansson further explain this phenomenon in their study.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Social Psychology Experiments

- Milgram Experiment

- Bobo Doll Experiment

- Stanford Prison Experiment

- Asch Experiment

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Social Psychology Experiments

- 2.1 Asch Figure

- 3 Bobo Doll Experiment

- 4 Good Samaritan Experiment

- 5 Stanford Prison Experiment

- 6.1 Milgram Experiment Ethics

- 7 Bystander Apathy

- 8 Sherif’s Robbers Cave

- 9 Social Judgment Experiment

- 10 Halo Effect

- 11 Thought-Rebound

- 12 Ross’ False Consensus Effect

- 13 Interpersonal Bargaining

- 14 Understanding and Belief

- 15 Hawthorne Effect

- 16 Self-Deception

- 17 Confirmation Bias

- 18 Overjustification Effect

- 19 Choice Blindness

- 20.1 Cognitive Dissonance

- 21.1 Social Group Prejudice

- 21.2 Intergroup Discrimination

- 21.3 Selective Group Perception

Choice Blindness is type of a broader phenomenon called the introspection illusion. Here, people wrongly think they have direct insight into the origins of their mental states, while treating other’s introspections as unreliable.

Let’s look at choice blindness this way. We think we want A but when we are given B, we make up all kinds of reasons that would persuade us into believing that B is a much better alternative and how we actually wanted it all along.

Lars Hall and Peter Johansson further explain choice blindness in their study.

Statement of the Problem

Peter Johansson together with his colleagues collectively investigated subjects’ insight into their own preferences using a new technique.

The researchers’ aim was to measure whether participants notice that something went wrong with their choice, during and after the experimental task.

Methodology

The experimenters presented subjects two photos of female faces and were asked which they found more attractive.

They were given a closer look at their "chosen" photograph and asked to verbally explain their choice immediately.

The trial was repeated 15 times for watch volunteer, using different pairs of faces but in three of the trials, unknown to the subjects, a card magic trick was used to extremely exchange one face for the other after a decision has been made. The subjects end up with the face they did not actually choose. And they were again, asked to explain why made them choose that particular face, even though it wasn’t really their first choice.

Majority of the participants failed to actually notice that the picture they were looking at wasn’t their original choice. Many subjects confabulated explanations of their choice.

For example, the subject may say:

I preferred this one because I prefer blondes.

when he in fact his original choice was the brunette, but he was handed a blonde. These must have been confabulated because they explain a preference that they did not really make to begin with.

Common sense would tell that all of us would of course notice such a big change in the outcome of a choice. But results showed that in 75% of the trials, the participants were blind to the mismatch. What’s more interesting is that, not only were a large number of participants were clueless of the switch, when allowed to take a longer look at their choice, they were able to make up a detailed explanation for why they chose that face when originally, they actually rejected it. The experimenters coined the term choice blindness for this failure to detect a mismatch.

A few, less than 1/10 of the manipulations were easily spotted by the participants. Not more than 20% of all manipulations were actually exposed, towards the end of each experiment.

After the experiment, the participants were presented a hypothetical scenario:

Suppose you were involved in an experiment where the faces you chose were switched. Would you notice?

84% of the participants said in the post-test interview that they would. Researchers called this choice blindness. When the truth was revealed to some, they expressed surprise and even disbelief.

Johansson further explains that when individuals were asked to reason out their choices, they remained confident in their verbal reports and had the same state of emotionality and expressed the same level of detail for faces they have and have not chosen.

Another important finding is that the effects of choice blindness go beyond snap judgements. Depending on what the participants say in response to the mismatched outcomes of choices (whether they give short or long explanations, give numerical rating or labelling, and so on), it was found that this interaction could change their future preferences to the extent that they come to prefer the previously rejected alternative. This gave the researchers a rare glimpse into the complicated dynamics of self-feedback ("I chose this, I publicly said so, therefore I must like it"), which is suspect as to what lies behind the formation of many everyday preferences.

The researchers did not know how or why choice blindness occur but they think it gets to the very heart of how we make decisions in our everyday life. According to Hall, one of the researchers, choice blindness doesn’t always happen. Therefore the concept of intention needs to be re-evaluated and investigated more closely.

There are several theories about decision-making that assume that we recognize when our intentions and the outcome of our choices do not match up but Johansson’s study shows that this assumption is not always the case. His experiment challenges both current theories of decision-making and common sense notions of choice and self-knowledge.

Application

Experiments on choice blindness can be used to provide a way to study subjectivity and introspection, topics once considered by scientists to be extremely difficult or even impossible to measure or evaluate scientifically.

Why does this happen? According to Jonah Lehrer, these confabulations are sometimes necessary half-truths that preserve the unity of oneself. Lehrer further explains: “just as a novelist creates a narrative, we create a sense of being. The self, in this sense, is our work of art, a fiction created by the mind in order to make sense of its own fragments.”

Introspection Illusion

‘Choice Blindness’ and How We Fool Ourselves

Confabulations by Jonah Lehrer

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Explorable.com (Mar 20, 2010). Choice Blindness. Retrieved Jan 27, 2025 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/choice-blindness

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Want to stay up to date? Follow us!

Save this course for later.

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

Thinking and Intelligence

Psych in real life: choice blindness, learning objectives.

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving, including choice blindness

Choice Blindness

Some choices are easy (“Do you want pepperoni or anchovies on your pizza?”) and some choices are hard (“Are you going to get Amazon Echo or Google Home?”), but most of us like to think that we “know our own mind”—that is, when we finally make a choice, we are clear about our decision. Research by psychologists in Sweden shows that this confidence in our own self-knowledge may not always be justified.

Choice blindness is the failure to recall a choice immediately after we have made that choice. If you go to an ice cream store, order a chocolate cone, and then accept a strawberry cone without noticing, that is choice blindness. If you go to an electronics store, select the new 55-inch Vizio television, and then fail to notice when they bring out (and expect you to pay for) the far more expensive 55-inch Sony television, that is choice blindness. If you order a burger and fries, and then don’t notice when soup-and-salad is placed in front of you, that is choice blindness.

As you have seen, Johannson, Hall, and their colleagues [1] found a method for inducing choice blindness in a laboratory setting, but they wanted to do more than simply demonstrate that people sometimes forget their choices. As psychological scientists, their goal is to explore an interesting phenomenon (i.e., choice blindness) to understand why it happens and to see if it tells us anything new about the way our minds work.

The Attraction Preference Experiment

You can learn the basics of the experiment conducted by Petter Johannson, Lars Hall and their colleagues by watching the following video [2] .

Johannson and Hall were curious to see how often people noticed that there was a mismatch between their choice and the picture they were told they had chosen. Here’s how the experiment worked. Imagine that you are sitting across a table from an experimenter, who is dressed in a long sleeved black shirt. He shows you a pair of pictures of head-and-shoulder shots of two males or two females. On each trial, you indicate which of the two people in the pictures you find more attractive. After you make your choice, the experimenter hands you the card you just pointed at and asks you to explain why you preferred this person.

Except that this didn’t always happen this way. Using a magician’s trick, on some trials, when the experimenter handed you the card, he actually handed you the card you did NOT choose.

You can view the transcript for “BBC Choice Blindness” here (opens in new window) .

The researchers tested 120 college students (70 female, 50 male). The pictures were all of women. As the video showed, they made their choice and then immediately explained the reasons for their preference. Only 13% of the switches were detected immediately. Approximately 10% more switches were mentioned “retrospectively”, where a participant initially justified choosing the switched face, but later indicated some suspicion that the wrong picture had been presented. Most participants who detected a switch attributed it to a technical error rather than suspecting that it was part of the research procedure.

But is it Real? The Value of Replication

The video you just watched described an experiment with a surprising result: more than 75% of the time, people make a choice and then, without indicating that anything is amiss, they proceed to justify a choice they did not make. But how solid is this study and how much can we believe these results? Maybe the choice blindness experiment reported real results, but (even assuming that the experimenters were completely honest and careful) could this have just been a weird outcome that will never happen again? In other words, is this a reliable result or just a fluke?

There is only one way to determine if a phenomenon is reliable, and that is replication . If you can’t replicate an effect, then you shouldn’t waste people’s time reading about it in a scientific paper.

There are at least three different types of replication.

- Direct Replication : Conduct exactly the same study again, usually with new participants from the same population as the original study. A successful replication would produce results similar to those in the original study.

- Systematic Replication : Conduct a study that is similar to the original one, but using slightly different methods or stimuli.

- Conceptual Replication : Conduct a very different study that still tests the original idea. In the current context, a conceptual replication would test the choice blindness idea using a method that did not involve choosing attractive people.

So, can you believe the choice blindness phenomenon?

In the years just before they published their 2005 study, the experimenters conducted two similar studies. For these studies, the pictures were presented on a computer screen, and the computer switched the pictures on the critical trials, so no magic was necessary. The results were very similar to the results of the study reported in the video above.

When the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) made the video, they reconstructed the experiment in a form very similar to the original. They reported that 80% of the participants did not notice any switching of pictures—a result very similar to the original. Unfortunately, without a published report of the study, it is impossible to know if the scientific standards of the original study had been maintained.

In 2014, researchers at the National University of Singapore reported a study similar to the experiment shown in the video. The stimuli were presented using a computer rather than a live experimenter. In addition to choosing one of the two faces, the participants rated their confidence in their choice and they typed their explanation of their preference. The faces were all of Caucasian women (as in the original study), but the participants were all of Asian descent (ethnic backgrounds: Chinese, Indian, and Vietnamese). Their results were similar to those of the original study.

Here is video showing another study by Johannson and Hall. The video has no sound—only subtitles.

You can view the transcript for “Using Choice Blindness to Shift Political Attitudes and Voter Intentions” here (opens in new window) .

Link to Learning

Visit this link to watch another video related about conceptual replication , this time related to taste.

From Phenomenon to Scientific Exploration

What you saw in the video is what a scientist would call a phenomenon—that is, a behavior that happens under certain conditions. The video showed that, if an experimenter is tricky enough, they can get people to justify choices that they never made. If you find this phenomenon interesting, then it may be worth your time to try to find out why it happens. (If you didn’t think it was interesting, then you will probably move on to find something that inspires you.)

Any of the choices in the list above could explain—fully or in part—the choice blindness phenomenon, but each idea would need to be tested. That is where the science comes in. The starting point for science is something interesting (a surprising phenomenon). If we are motivated to ask why something happened, then we jump into the real work of science: exploring possible explanations.

The next scientific step systematically (i.e., carefully and with specific purposes) changes elements of the procedures or stimuli to see how these changes affect the results. Remember that our dependent variable is the probability that the change in faces will be detected. So now we try to learn more about change blindness by seeing how changing specific details (independent variables) either increase or decrease people’s likelihood of noticing the switch in faces.

Two Variables: Time and Similarity

In the 2005 study, Johansson and Hall looked at two interesting variables that might influence detection of the mismatch. First, how rushed were the participants to make their decision? They gave some people only 2 seconds to choose the more attractive person. Others were given 5 seconds, and another group was given as long as people wanted (free choice). Should more time make someone more likely or less likely to notice that they have been given the picture they did not choose?

The second variable was how similar the two faces were to one another. In some cases, the two faces were similar to each other in general features, while in other cases the two faces were more distinctly different. If the two faces are quite different, how should that affect your ability to notice?

Figure 1 . Johansson and Hall wanted to know if people were more likely to notice a similar or dissimilar image when shown a picture they did not chose.

If we put the two manipulated variables (time and similarity) together, that gives us six conditions:

Figure 2 . The six conditions of the experiment show that people were shown either similar or dissimilar faces, or given various amounts of time.

In the figure below, adjust the bars to fit your predictions about how often people would notice the picture switch. Higher bars mean people more often noticed that the cards had been switched. Lower bars mean that people made one choice and didn’t notice when they were given the wrong picture. This isn’t easy because you need to take account of the two variables: (1) amount of time looking at the pictures before your choice and (2) similarity of the faces in the pictures.

Most people make predictions that put the red bars lowest, the purple bars in the middle, and the green bars highest. This supports the idea that the more time you have to look at the pictures, the more likely you are to notice that the picture you have chosen is not the one the experimenter gave you.

People also expect that the switch will be more noticeable if the faces are dissimilar. For example, if we look at the green bars with unlimited time, it makes sense that people will generally notice when the faces have been switched on them, and this is much greater when the two faces are very different (dissimilar condition) than when they are similar (similar condition).

Most people find it hard to believe that lots of people will be tricked by the switch in faces, even if the experimenter has good magician skills. So, what did happen?

First, people generally did not notice the change in faces. Overall, participants on fewer than 20% of the trials noticed any of the card switches. Most participants simply did not realize that the faces had been switched, and many were either very surprised when they were told what had happened or they simply didn’t believe the experimenters.

There was an effect of time. The red bars (2 seconds to choose) are lower than the purple bars (5 seconds to choose), and the purple bars are lower than the green bars (unlimited time to choose), but the differences are fairly modest. The bigger surprise was the LACK of difference between the similar and dissimilar faces. In all three time conditions, there was no significant difference—barely a measurable difference–between the similar and dissimilar faces conditions. [3]

What Do These Results Tell Us?

With just these results, we are still a long way from understanding choice blindness. The experiment you just read takes us a couple of steps in the right direction. First, the similarity of the faces is (surprisingly) not a particularly influential factor. This does not mean that the case is closed and similarity is unimportant, but it does suggest that confusion due to similarity may not be the whole story.

The amount of time participants had to choose did have a big influence on detection of a switch in faces. When the participants were rushed (2 second condition), the chance of detecting a change was very slight. Given 5 seconds, detection improved, but not by a great amount. Unlimited time to choose made a substantial difference, but detection was still only around 25%. These results suggest that time to choose may be an important factor, but it is not the whole story. Furthermore, we are still not sure what it was about the extra time that led to improved detection. Did more time allow the participants to remember the faces better? Or perhaps their memory for faces was not improved, but they had more time to think of reasons they preferred one person over the other (her earrings, the way her hair flowed, a look in her eyes). These preferred features could signal to them that something was missing when the wrong picture was presented.

If you explore the research literature on choice blindness, you will find that the phenomenon has been studied from many angles. Experiments have been conducted in university laboratories and on the streets of a city in the Netherlands. Choice blindness in the video involved remembering what someone looked like, but choices involving sound, taste, and smell have also produced choice blindness. Even people’s judgments about their own personality and preferences is open to choice blindness. We don’t fully understand when and why choice blindness occurs, but it is an intriguing phenomenon, open to scientific curiosity.

A Final Thought

Petter Johannson’s 2016 TED Talk from 2016 describes choice blindness to an audience . At the end he acknowledges that choice blindness can make people look silly or worse, but he also believes that this research provides us with an insight about people that may be reason for hope in a world seemingly full of discord and bereft of compromise.

Here are the closing lines from his TED talk:

This [choice blindness] may all seem a bit disturbing. But if you want to look at it from a positive direction, it could be seen as showing: Okay, so we’re all a little bit more flexible than we think. We can change our minds. Our attitudes are not set in stone. And we can also change the minds of others if we can only get them to engage with the issue and see it from the opposite view. … Getting rid of the need to stay consistent is actually a huge relief and makes [social] life so much easier to live. So the conclusion must be, “Know that you don’t know yourself. Or at least not as well as you think you do.”

Candela Citations

- Psychology in Real Life: Choice Blindness. Authored by : Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Actors Headshots . Authored by : Vanity Studios. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/149481436@N03/34277183806/in/photostream/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/boy-portrait-outdoors-facial-men-s-3566903/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- man with beard. Authored by : Simon Robben. Provided by : Pexels. Located at : https://www.pexels.com/photo/face-facial-hair-fine-looking-guy-614810/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- image of businessman. Authored by : RoyalAnwar. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/model-businessman-corporate-2911332/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- man in black shirt. Authored by : songjayjay. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/face-men-s-asia-shirts-blacj-young-1391628/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- woman headshot. Authored by : Richard Ha. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/richardha101/31951459743/in/photolist-QFrzNX-V9Amf2-UM2ZU5-HMQxnd-WmpZx1-5ztiGT-ovm92d-28C1Eyi-qhwZzM-8szjMV-YRsM5B-LCTNFR-LtgVC9-LCUgd8-8gRLbQ-REArrY-WQNThG-ph52sx-2bC2DwH-qE61yp-28NspiC-21h8cj4-RVoBBc-29GiNJ3-21QEU6M-M1YTcp-PePwTJ-LALKtr-RVoBtg-Ry1bpy-FVr9BB-282GDDG-V7zSQJ-NwmdK9-29bSs5N-29mSb5G-272dN8p-26brtas-28tTQWf-RS1osg-WHoUSc-25uETMH-D7crwK-28m9fEh-25taZPB-JCwqE7-241e8Xp-265Ce4A-22V7VVo-25N7i4q . License : CC BY: Attribution

- businesswoman headshot. Authored by : Richard Rives. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/richpat2/38251159285/in/photostream/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- BBC Choice Blindness. Authored by : BBC. Provided by : ChoiceBlindnessLab. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRqyw-EwgTk . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Using Choice Blindness to Shift Political Attitudes and Voter Intentions. Provided by : ChoiceBlindnessLab. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_htNx0eWmgs . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Petter Johannson, Lars Hall, Sverker Sikström, & Andreas Olsson. (2005). Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task. Science, 310 (7 October 2005), 116-119. ↵

- The video is a segment from a BBC video from the science series called Horizons. This particular show was about decision making ↵

- The results are more complex than the figure suggests. The data shown above are limited to first detections of the switch in pictures. After people notice that there has been a switch, they tend to be a bit suspicious and they are more vigilant about noticing changes. If all trials are taken into account, the data are still similar to these, but not quite as pretty. See the original paper for all the details. ↵

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Choice Blindness in Psychology

We aren't always fully aware of the choices we make

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

What the Research Says

How choice blindness influences decisions, what causes choice blindness, real-world implications.

The concept of choice blindness suggests that people are not always aware of their choices and preferences. Choice blindness is a part of a cognitive phenomenon known as the introspection illusion . Essentially, people incorrectly believe that they fully understand the roots of their emotions and thoughts, yet believe that other people's introspections are largely unreliable.

According to research on this topic, even when you don't get what you want, there's a strong chance that you won't even notice. And you may even defend a choice just because you think it's the one you made.

For example, let's say you've been asked to taste two different types of jams and choose your favorite. You are then offered another taste of the one you selected as your favorite and asked to explain why you chose it. Do you think that you would notice if the jam that you had initially rejected was presented to you as your "favorite?"

In a pioneering study on the concept of choice blindness, researchers Johansson, Hall, Sikstrom, and Olsson examined how people often overlook differences between their intentions and outcomes. The study involved having participants look at images of two different female faces for between two to five seconds. The participants then rated which face they found the most attractive.

The researchers then changed the photo that the participants thought they had chosen to that of an entirely different woman, and the participants were asked to describe why they found the woman attractive.

Surprisingly, only 13% of the participants noticed the switch. In fact, many went on to describe the reasons why they found the face attractive, even though it was not the woman that they had chosen at all.

Further research demonstrated how these effects could influence other types of choices. In 2010 social scientists Petter Johansson, Lars Hall, and their colleagues presented just such a scenario to supermarket volunteers. They found that fewer than 20% of participants noticed that they tasted the jam they had turned down just a few moments earlier. In many cases, the difference between the two flavors differed dramatically, ranging from spicy to sweet to bitter.

In other cases, people ended up tasting the exact same jam twice. Yet when asked, people would then explain how the two tastes were different.

Such findings demonstrate that people don't always understand the inner workings of their own minds and are frequently blind to the factors that influence their choices.

Researchers have demonstrated how choice blindness impacts visual, taste, and smell preferences, but is it possible that it might have an influence on more important choices?

In a 2013 study by Hall and colleagues, researchers investigated how choice blindness might influence political attitudes. During a Swedish general election, participants were asked to state who they planned to vote for and were then asked to select their opinion for each of a number of wedge issues. Then using sleight of hand, the researchers altered their replies so that they were actually on the opposing political point of view. Participants were then asked to justify their responses on the altered issues.

Consistent with earlier research on choice blindness, only 22% of the manipulated responses were detected and more than 90% of the participants accepted and then endorsed at least one altered response.

These results suggest that our political attitudes may be more open to change than we may realize.

How do the experts define choice blindness? According to Johansson and Hall, we frequently fail to notice when we are presented with something different from what we really want, and, we will come up with reasons to defend this "choice."

So why do so many people fail to notice these switches? Are we less aware of our preferences than we think we are?

Interest in the choice at hand is one factor that might play a role. When an issue is more important to us, we might be likely to notice mismatches between what we choose and what we actually get. Additionally, the similarity of choices can have an effect—we may be less likely to notice small differences when presented with a choice we did not make.

Choice blindness can have important ramifications in the real world. The ability to recognize faces plays a major role in our everyday lives. While we might think that we are good at recognizing a face that we had previously selected, the reality is that we are actually quite poor at detecting switches.

While this kind of mistake may not always be significant, there are times when it can be life-changing. For example, eyewitness testimony is one of the more common means of identifying the supposed perpetrator of a given crime, but this kind of testimony—while compelling—is far less accurate than evidence such as DNA. It could be much easier than we think for a witness—through no malice of their own—to be manipulated into positively and confidently identifying the wrong person.

The next time you're making a decision, perhaps it will help to take an extra beat to fully understand and process your choice as you make it. You may be less susceptible to mistaking that choice for something else in the future.

Johansson P, Hall L, Sikstrom S, Olsson A. Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task . Science . 2005;310(5745):116-119. doi:10.1126/science.1111709

Hall L, Johansson P, Tärning B, Sikström S, Deutgen T. Magic at the marketplace: Choice blindness for the taste of jam and the smell of tea . Cognition. 2010;117(1): 54-61. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.06.010

Hall L, Strandberg T, Pärnamets P, Lind A, Tärning B, Johansson P. How the polls can be both spot on and dead wrong: Using choice blindness to shift political attitudes and voter intentions . PLoS ONE. 2013; 8(4) : e60554. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060554

O’Neill Shermer L, Rose KC, Hoffman A. Perceptions and credibility: Understanding the nuances of eyewitness testimony . Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice . 2011;27(2):183-203. doi:10.1177/1043986211405886

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Sad Facial Expressions Increase Choice Blindness

Zhijie zhang, wenfeng feng.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Mario Weick, University of Kent, United Kingdom

Reviewed by: Anna Sagana, Maastricht University, Netherlands; Mariya Kirichek, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, United Kingdom

*Correspondence: Zhijie Zhang [email protected]

Wenfeng Feng [email protected]

This article was submitted to Personality and Social Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2017 Aug 13; Accepted 2017 Dec 18; Collection date 2017.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

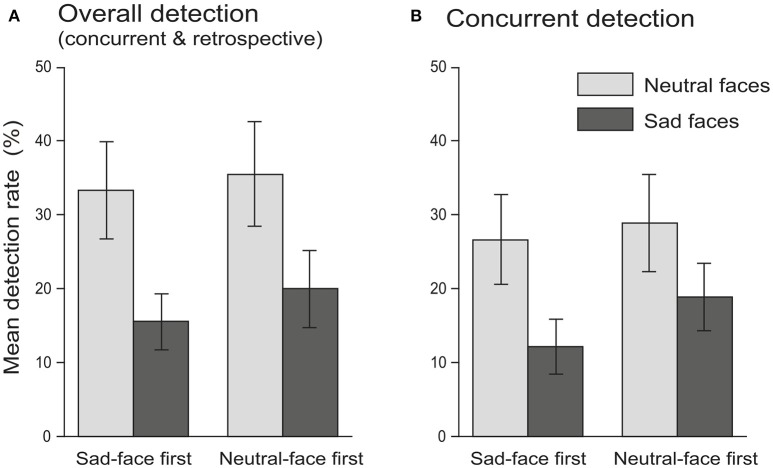

Previous studies have discovered a fascinating phenomenon known as choice blindness—individuals fail to detect mismatches between the face they choose and the face replaced by the experimenter. Although previous studies have reported a couple of factors that can modulate the magnitude of choice blindness, the potential effect of facial expression on choice blindness has not yet been explored. Using faces with sad and neutral expressions (Experiment 1) and faces with happy and neutral expressions (Experiment 2) in the classic choice blindness paradigm, the present study investigated the effects of facial expressions on choice blindness. The results showed that the detection rate was significantly lower on sad faces than neutral faces, whereas no significant difference was observed between happy faces and neutral faces. The exploratory analysis of verbal reports found that participants who reported less facial features for sad (as compared to neutral) expressions also tended to show a lower detection rate of sad (as compared to neutral) faces. These findings indicated that sad facial expressions increased choice blindness, which might have resulted from inhibition of further processing of the detailed facial features by the less attractive sad expressions (as compared to neutral expressions).

Keywords: choice blindness, facial expressions, sad faces, happy faces, neutral faces

Introduction