- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

Key Study: HM’s case study (Milner and Scoville, 1957)

Travis Dixon January 29, 2019 Biological Psychology , Cognitive Psychology , Key Studies

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

HM’s case study is one of the most famous and important case studies in psychology, especially in cognitive psychology. It was the source of groundbreaking new knowledge on the role of the hippocampus in memory.

Background Info

“Localization of function in the brain” means that different parts of the brain have different functions. Researchers have discovered this from over 100 years of research into the ways the brain works. One such study was Milner’s case study on Henry Molaison.

The memory problems that HM experienced after the removal of his hippocampus provided new knowledge on the role of the hippocampus in memory formation (image: wikicommons)

At the time of the first study by Milner, HM was 29 years old. He was a mechanic who had suffered from minor epileptic seizures from when he was ten years old and began suffering severe seizures as a teenager. These may have been a result of a bike accident when he was nine. His seizures were getting worse in severity, which resulted in HM being unable to work. Treatment for his epilepsy had been unsuccessful, so at the age of 27 HM (and his family) agreed to undergo a radical surgery that would remove a part of his brain called the hippocampus . Previous research suggested that this could help reduce his seizures, but the impact it had on his memory was unexpected. The Doctor performing the radical surgery believed it was justified because of the seriousness of his seizures and the failures of other methods to treat them.

Methods and Results

In one regard, the surgery was successful as it resulted in HM experiencing less seizures. However, immediately after the surgery, the hospital staff and HM’s family noticed that he was suffering from anterograde amnesia (an inability to form new memories after the time of damage to the brain):

Here are some examples of his memory loss described in the case study:

- He could remember something if he concentrated on it, but if he broke his concentration it was lost.

- After the surgery the family moved houses. They stayed on the same street, but a few blocks away. The family noticed that HM as incapable of remembering the new address, but could remember the old one perfectly well. He could also not find his way home alone.

- He could not find objects around the house, even if they never changed locations and he had used them recently. His mother had to always show him where the lawnmower was in the garage.

- He would do the same jigsaw puzzles or read the same magazines every day, without ever apparently getting bored and realising he had read them before. (HM loved to do crossword puzzles and thought they helped him to remember words).

- He once ate lunch in front of Milner but 30 minutes later was unable to say what he had eaten, or remember even eating any lunch at all.

- When interviewed almost two years after the surgery in 1955, HM gave the date as 1953 and said his age was 27. He talked constantly about events from his childhood and could not remember details of his surgery.

Later testing also showed that he had suffered some partial retrograde amnesia (an inability to recall memories from before the time of damage to the brain). For instance, he could not remember that one of his favourite uncles passed away three years prior to his surgery or any of his time spent in hospital for his surgery. He could, however, remember some unimportant events that occurred just before his admission to the hospital.

Brenda Milner studied HM for almost 50 years – but he never remembered her.

Results continued…

His memories from events prior to 1950 (three years before his surgery), however, were fine. There was also no observable difference to his personality or to his intelligence. In fact, he scored 112 points on his IQ after the surgery, compared with 104 previously. The IQ test suggested that his ability in arithmetic had apparently improved. It seemed that the only behaviour that was affected by the removal of the hippocampus was his memory. HM was described as a kind and gentle person and this did not change after his surgery.

The Star Tracing Task

In a follow up study, Milner designed a task that would test whether or not HMs procedural memory had been affected by the surgery. He was to trace an outline of a star, but he could only see the mirrored reflection. He did this once a day over a period of a few days and Milner observed that he became faster and faster. Each time he performed the task he had no memory of ever having done it before, but his performance kept improving. This is further evidence for localization of function – the hippocampus must play a role in declarative (explicit) memory but not procedural (implicit) memory.

Cognitive psychologists have categorized memories into different types. HM’s study suggests that the hippocampus is essential for explicit (conscious) and declarative memory, but not implicit (unconscious) procedural memory.

Was his memory 100% gone? Another follow-up study

Interestingly, HM showed signs of being able to remember famous people who had only become famous after his surgery, like Lee Harvey Oswald (who assassinated JFK in 1963). (Image: wikicommons)

Another fascinating follow-up study was conducted by two researchers who wanted to see if HM had learned anything about celebrities that became famous after his surgery. At first they tested his knowledge of celebrities from before his surgery, and he knew these just as well as controls. They then showed him two names at a time, one a famous name (e.g. Liza Minelli, Lee Harvey Oswald) and the other was a name randomly taken from the phonebook. He was asked to choose the famous name and he was correct on a significant number of trials (i.e. the statistics tests suggest he wasn’t just guessing). Even more incredible was that he remembered some details about these people when asked why they were famous. For example, he could remember that Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated the president. One explanation given for the memory of these facts is that there was an emotional component. E.g. He liked these people, or the assassination was so violent, that he could remember a few details.

HM became a hugely important case study for neuro and cognitive Psychologists. He was interviewed and tested by over 100 psychologists during the 53 years after his operation. Directly after his surgery, he lived at home with his parents as he was unable to live independently. He moved to a nursing home in 1980 and stayed there until his death in 2008. HM donated his brain to science and it was sliced into 2,401 thin slices that will be scanned and published electronically.

Critical Thinking Considerations

- How does this case study demonstrate localization of function in the brain? (e.g.c reating new long-term memories; procedural memories; storing and retrieving long term memories; intelligence; personality) ( Application )

- What are the ethical considerations involved in this study? ( Analysis )

- What are the strengths and limitations of this case study? ( Evaluation )

- Why would ongoing studies of HM be important? (Think about memory, neuroplasticity and neurogenesis) ( Analysis/Synthesis/Evaluation )

- How can findings from this case study be used to support and/or challenge the Multi-store Model of Memory? ( Application / Synthesis/Evaluation )

Exam Tips This study can be used for the following topics: Localization – the role of the hippocampus in memory Techniques to study the brain – MRI has been used to find out the exact location and size of damage to HM’s brain Bio and cognitive approach research method s – case study Bio and cognitive approach ethical considerations – anonymity Emotion and cognition – the follow-up study on HM and memories of famous people could be used in an essay to support the idea that emotion affects memory Models of memory – the multi-store model : HM’s study provides evidence for the fact that our memories all aren’t formed and stored in one place but travel from store to store (because his transfer from STS to LTS was damaged – if it was all in one store this specific problem would not occur)

Milner, Brenda. Scoville, William Beecher. “Loss of Recent Memory after Bilateral Hippocampal Lesions”. The Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1957; 20: 11 21. (Accessed from web.mit.edu )

The man who couldn’t remember”. nova science now. an interview with brenda corkin . 06.01.2009. .

Here’s a good video recreation documentary of HM’s case study…

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

Cognitive Approach in Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of the mind as an information processor. It concerns how we take in information from the outside world, and how we make sense of that information.

Cognitive psychology studies mental processes, including how people perceive, think, remember, learn, solve problems, and make decisions.

Cognitive psychologists try to build cognitive models of the information processing that occurs inside people’s minds, including perception, attention, language, memory, thinking, and consciousness.

Cognitive psychology became of great importance in the mid-1950s. Several factors were important in this:

- Dissatisfaction with the behaviorist approach in its simple emphasis on external behavior rather than internal processes.

- The development of better experimental methods.

- Comparison between human and computer processing of information . Using computers allowed psychologists to try to understand the complexities of human cognition by comparing it with computers and artificial intelligence.

The emphasis of psychology shifted away from the study of conditioned behavior and psychoanalytical notions about the study of the mind, towards the understanding of human information processing using strict and rigorous laboratory investigation.

Summary Table

Theoretical assumptions.

Mediational processes occur between stimulus and response:

The behaviorist approach only studies external observable (stimulus and response) behavior that can be objectively measured.

They believe that internal behavior cannot be studied because we cannot see what happens in a person’s mind (and therefore cannot objectively measure it).

However, cognitive psychologists consider it essential to examine an organism’s mental processes and how these influence behavior.

Cognitive psychology assumes a mediational process occurs between stimulus/input and response/output.

These are mediational processes because they mediate (i.e., go-between) between the stimulus and the response. They come after the stimulus and before the response.

Instead of the simple stimulus-response links proposed by behaviorism, the mediational processes of the organism are essential to understand.

Without this understanding, psychologists cannot have a complete understanding of behavior.

The mediational (i.e., mental) event could be memory , perception , attention or problem-solving, etc.

- Perception : how we process and interpret sensory information.

- Attention : how we selectively focus on certain aspects of our environment.

- Memory : how we encode, store, and retrieve information.

- Language : how we acquire, comprehend, and produce language.

- Problem-solving and decision-making : how we reason, make judgments, and solve problems.

- Schemas : Cognitive psychologists assume that people’s prior knowledge, beliefs, and experiences shape their mental processes.

For example, the cognitive approach suggests that problem gambling results from maladaptive thinking and faulty cognitions, which both result in illogical errors.

Gamblers misjudge the amount of skill involved with ‘chance’ games, so they are likely to participate with the mindset that the odds are in their favour and that they may have a good chance of winning.

Therefore, cognitive psychologists say that if you want to understand behavior, you must understand these mediational processes.

Psychology should be seen as a science:

This assumption is based on the idea that although not directly observable, the mind can be investigated using objective and rigorous methods, similar to how other sciences study natural phenomena.

Controlled experiments

The cognitive approach believes that internal mental behavior can be scientifically studied using controlled experiments .

It uses the results of its investigations to make inferences about mental processes.

Cognitive psychology uses highly controlled laboratory experiments to avoid the influence of extraneous variables .

This allows the researcher to establish a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

These controlled experiments are replicable, and the data obtained is objective (not influenced by an individual’s judgment or opinion) and measurable. This gives psychology more credibility.

Operational definitions

Cognitive psychologists develop operational definitions to study mental processes scientifically.

These definitions specify how abstract concepts, such as attention or memory, can be measured and quantified (e.g., verbal protocols of thinking aloud). This allows for reliable and replicable research findings.

Falsifiability

Falsifiability in psychology refers to the ability to disprove a theory or hypothesis through empirical observation or experimentation. If a claim is not falsifiable, it is considered unscientific.

Cognitive psychologists aim to develop falsifiable theories and models, meaning they can be tested and potentially disproven by empirical evidence.

This commitment to falsifiability helps to distinguish scientific theories from pseudoscientific or unfalsifiable claims.

Empirical evidence

Cognitive psychologists rely on empirical evidence to support their theories and models.

They collect data through various methods, such as experiments, observations, and questionnaires, to test hypotheses and draw conclusions about mental processes.

Cognitive psychologists assume that mental processes are not random but are organized and structured in specific ways. They seek to identify the underlying cognitive structures and processes that enable people to perceive, remember, and think.

Cognitive psychologists have made significant contributions to our understanding of mental processes and have developed various theories and models, such as the multi-store model of memory , the working memory model , and the dual-process theory of thinking.

Humans are information processors:

The idea of information processing was adopted by cognitive psychologists as a model of how human thought works.

The information processing approach is based on several assumptions, including:

- Information is processed by a series of systems : The information processing approach proposes that a series of cognitive systems, such as attention, perception, and memory, process information from the environment. Each system plays a specific role in processing the information and passing it along to the next stage.

- Processing systems transform information : As information passes through these cognitive systems, it is transformed or modified in systematic ways. For example, incoming sensory information may be filtered by attention, encoded into memory, or used to update existing knowledge structures.

- Research aims to specify underlying processes and structures : The primary goal of research within the information processing approach is to identify, describe, and understand the specific cognitive processes and mental structures that underlie various aspects of cognitive performance, such as learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

- Human information processing resembles computer processing : The information processing approach draws an analogy between human cognition and computer processing. Just as computers take in information, process it according to specific algorithms, and produce outputs, the human mind is thought to engage in similar processes of input, processing, and output.

Computer-Mind Analogy

The computer-brain metaphor, or the information processing approach, is a significant concept in cognitive psychology that likens the human brain’s functioning to that of a computer.

This metaphor suggests that the brain, like a computer, processes information through a series of linear steps, including input, storage, processing, and output.

According to this assumption, when we interact with the environment, we take in information through our senses (input).

This information is then processed by various cognitive systems, such as perception, attention, and memory. These systems work together to make sense of the input, organize it, and store it for later use.

During the processing stage, the mind performs operations on the information, such as encoding, transforming, and combining it with previously stored knowledge. This processing can involve various cognitive processes, such as thinking, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

The processed information can then be used to generate outputs, such as actions, decisions, or new ideas. These outputs are based on the information that has been processed and the individual’s goals and motivations.

This has led to models showing information flowing through the cognitive system, such as the multi-store memory model.

The information processing approach also assumes that the mind has a limited capacity for processing information, similar to a computer’s memory and processing limitations.

This means that humans can only attend to and process a certain amount of information at a given time, and that cognitive processes can be slowed down or impaired when the mind is overloaded.

The Role of Schemas

A schema is a “packet of information” or cognitive framework that helps us organize and interpret information. It is based on previous experience.

Cognitive psychologists assume that people’s prior knowledge, beliefs, and experiences shape their mental processes. They investigate how these factors influence perception, attention, memory, and thinking.

Schemas help us interpret incoming information quickly and effectively, preventing us from being overwhelmed by the vast amount of information we perceive in our environment.

Schemas can often affect cognitive processing (a mental framework of beliefs and expectations developed from experience). As people age, they become more detailed and sophisticated.

However, it can also lead to distortion of this information as we select and interpret environmental stimuli using schemas that might not be relevant.

This could be the cause of inaccuracies in areas such as eyewitness testimony. It can also explain some errors we make when perceiving optical illusions.

1. Behaviorist Critique

B.F. Skinner criticizes the cognitive approach. He believes that only external stimulus-response behavior should be studied, as this can be scientifically measured.

Therefore, mediation processes (between stimulus and response) do not exist as they cannot be seen and measured.

Behaviorism assumes that people are born a blank slate (tabula rasa) and are not born with cognitive functions like schemas , memory or perception .

Due to its subjective and unscientific nature, Skinner continues to find problems with cognitive research methods, namely introspection (as used by Wilhelm Wundt).

2. Complexity of mental experiences

Mental processes are highly complex and multifaceted, involving a wide range of cognitive, affective, and motivational factors that interact in intricate ways.

The complexity of mental experiences makes it difficult to isolate and study specific mental processes in a controlled manner.

Mental processes are often influenced by individual differences, such as personality, culture, and past experiences, which can introduce variability and confounds in research .

3. Experimental Methods

While controlled experiments are the gold standard in cognitive psychology research, they may not always capture real-world mental processes’ complexity and ecological validity.

Some mental processes, such as creativity or decision-making in complex situations, may be difficult to study in laboratory settings.

Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers believes that using laboratory experiments by cognitive psychology has low ecological validity and creates an artificial environment due to the control over variables .

Rogers emphasizes a more holistic approach to understanding behavior.

The cognitive approach uses a very scientific method that is controlled and replicable, so the results are reliable.

However, experiments lack ecological validity because of the artificiality of the tasks and environment, so they might not reflect the way people process information in their everyday lives.

For example, Baddeley (1966) used lists of words to find out the encoding used by LTM.

However, these words had no meaning to the participants, so the way they used their memory in this task was probably very different from what they would have done if the words had meaning for them.

This is a weakness, as the theories might not explain how memory works outside the laboratory.

4. Computer Analogy

The information processing paradigm of cognitive psychology views the minds in terms of a computer when processing information.

However, although there are similarities between the human mind and the operations of a computer (inputs and outputs, storage systems, and the use of a central processor), the computer analogy has been criticized.

For example, the human mind is characterized by consciousness, subjective experience, and self-awareness , which are not present in computers.

Computers do not have feelings, emotions, or a sense of self, which play crucial roles in human cognition and behavior.

The brain-computer metaphor is often used implicitly in neuroscience literature through terms like “sensory computation,” “algorithms,” and “neural codes.” However, it is difficult to identify these concepts in the actual brain.

5. Reductionist

The cognitive approach is reductionist as it does not consider emotions and motivation, which influence the processing of information and memory. For example, according to the Yerkes-Dodson law , anxiety can influence our memory.

Such machine reductionism (simplicity) ignores the influence of human emotion and motivation on the cognitive system and how this may affect our ability to process information.

Early theories of cognitive approach did not always recognize physical ( biological psychology ) and environmental (behaviorist approach) factors in determining behavior.

However, it’s important to note that modern cognitive psychology has evolved to incorporate a more holistic understanding of human cognition and behavior.

1. Importance of cognitive factors versus external events

Cognitive psychology emphasizes the role of internal cognitive processes in shaping emotional experiences, rather than solely focusing on external events.

Beck’s cognitive theory suggests that it is not the external events themselves that lead to depression, but rather the way an individual interprets and processes those events through their negative schemas.

This highlights the importance of addressing cognitive factors in the treatment of depression and other mental health issues.

Social exchange theory (Thibaut & Kelly, 1959) emphasizes that relationships are formed through internal mental processes, such as decision-making, rather than solely based on external factors.

The computer analogy can be applied to this concept, where individuals observe behaviors (input), process the costs and benefits (processing), and then make a decision about the relationship (output).

2. Interdisciplinary approach

While early cognitive psychology may have neglected physical and environmental factors, contemporary cognitive psychology has increasingly integrated insights from other approaches.

Cognitive psychology draws on methods and findings from other scientific disciplines, such as neuroscience , computer science, and linguistics, to inform their understanding of mental processes.

This interdisciplinary approach strengthens the scientific basis of cognitive psychology.

Cognitive psychology has influenced and integrated with many other approaches and areas of study to produce, for example, social learning theory , cognitive neuropsychology, and artificial intelligence (AI).

3. Real World Applications

Another strength is that the research conducted in this area of psychology very often has applications in the real world.

By highlighting the importance of cognitive processing, the cognitive approach can explain mental disorders such as depression.

Beck’s cognitive theory of depression argues that negative schemas about the self, the world, and the future are central to the development and maintenance of depression.

These negative schemas lead to biased processing of information, selective attention to negative aspects of experience, and distorted interpretations of events, which perpetuate the depressive state.

By identifying the role of cognitive processes in mental disorders, cognitive psychology has informed the development of targeted interventions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy aims to modify the maladaptive thought patterns and beliefs that underlie emotional distress, helping individuals to develop more balanced and adaptive ways of thinking.

CBT’s basis is to change how people process their thoughts to make them more rational or positive.

Through techniques such as cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments, and guided discovery, CBT helps individuals to challenge and change their negative schemas, leading to improvements in mood and functioning.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been very effective in treating depression (Hollon & Beck, 1994), and moderately effective for anxiety problems (Beck, 1993).

Issues and Debates

Free will vs. determinism.

The cognitive approach’s position is unclear. It argues that cognitive processes are influenced by experiences and schemas, which implies a degree of determinism.

On the other hand, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) operates on the premise that individuals can change their thought patterns, suggesting a capacity for free will.

Nature vs. Nurture

The cognitive approach takes an interactionist view of the debate, acknowledging the influence of both nature and nurture on cognitive processes.

It recognizes that while some cognitive abilities, such as language acquisition, may have an innate component (nature), experiences and learning (nurture) also shape the way information is processed.

Holism vs. Reductionism

The cognitive approach tends to be reductionist in its methodology, as it often studies cognitive processes in isolation.

For example, researchers may focus on memory processes without considering the influence of other cognitive functions or environmental factors.

While this approach allows for more controlled study, it may lack ecological validity, as in real life, cognitive processes typically interact and function simultaneously.

Idiographic vs. Nomothetic

The cognitive approach is primarily nomothetic, as it seeks to establish general principles and theories of information processing that apply to all individuals.

It aims to identify universal patterns and mechanisms of cognition rather than focusing on individual differences.

History of Cognitive Psychology

- Wolfgang Köhler (1925) – Köhler’s book “The Mentality of Apes” challenged the behaviorist view by suggesting that animals could display insightful behavior, leading to the development of Gestalt psychology.

- Norbert Wiener (1948) – Wiener’s book “Cybernetics” introduced concepts such as input and output, which influenced the development of information processing models in cognitive psychology.

- Edward Tolman (1948) – Tolman’s work on cognitive maps in rats demonstrated that animals have an internal representation of their environment, challenging the behaviorist view.

- George Miller (1956) – Miller’s paper “The Magical Number 7 Plus or Minus 2” proposed that short-term memory has a limited capacity of around seven chunks of information, which became a foundational concept in cognitive psychology.

- Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon (1972) – Newell and Simon developed the General Problem Solver, a computer program that simulated human problem-solving, contributing to the growth of artificial intelligence and cognitive modeling.

- George Miller and Jerome Bruner (1960) – Miller and Bruner established the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard, which played a significant role in the development of cognitive psychology as a distinct field.

- Ulric Neisser (1967) – Neisser’s book “Cognitive Psychology” formally established cognitive psychology as a separate area of study, focusing on mental processes such as perception, memory, and thinking.

- Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968) – Atkinson and Shiffrin proposed the Multi-Store Model of memory, which divided memory into sensory, short-term, and long-term stores, becoming a key model in the study of memory.

- Eleanor Rosch’s (1970s) research on natural categories and prototypes, which influenced the study of concept formation and categorization.

- Endel Tulving’s (1972) distinction between episodic and semantic memory, which further developed the understanding of long-term memory.

- Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) proposal of the Working Memory Model, which expanded on the concept of short-term memory and introduced the idea of a central executive.

- Marvin Minsky’s (1975) framework of frames in artificial intelligence, which influenced the understanding of knowledge representation in cognitive psychology.

- David Rumelhart and Andrew Ortony’s (1977) work on schema theory, which described how knowledge is organized and used for understanding and remembering information.

- Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman’s (1970s-80s) research on heuristics and biases in decision making, which led to the development of behavioral economics and the study of judgment and decision-making.

- David Marr’s (1982) computational theory of vision, which provided a framework for understanding visual perception and influenced the field of computational cognitive science.

- The development of connectionism and parallel distributed processing (PDP) models in the 1980s, which provided an alternative to traditional symbolic models of cognitive processes.

- Noam Chomsky’s (1980s) theory of Universal Grammar and the language acquisition device, which influenced the study of language and cognitive development.

- The emergence of cognitive neuroscience in the 1990s, which combined techniques from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and computer science to study the neural basis of cognitive processes.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Chapter: Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Spence, K. W., & Spence, J. T. The psychology of learning and motivation (Volume 2). New York: Academic Press. pp. 89–195.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47-89). Academic Press.

Beck, A. T, & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace and Company.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use . Praeger.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (Ed.). (1995). The Cognitive Neurosciences. MIT Press.

Hollon, S. D., & Beck, A. T. (1994). Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In A. E. Bergin & S.L. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 428—466) . New York: Wiley.

Köhler, W. (1925). An aspect of Gestalt psychology. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 32(4) , 691-723.

Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information . W. H. Freeman.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review , 63 (2): 81–97.

Minsky, M. (1975). A framework for representing knowledge. In P. H. Winston (Ed.), The Psychology of Computer Vision (pp. 211-277). McGraw-Hill.

Neisser, U (1967). Cognitive psychology . Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York

Newell, A., & Simon, H. (1972). Human problem solving . Prentice-Hall.

Rosch, E. H. (1973). Natural categories. Cognitive Psychology, 4 (3), 328-350.

Rumelhart, D. E., & McClelland, J. L. (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 1: Foundations. MIT Press.

Rumelhart, D. E., & Ortony, A. (1977). The representation of knowledge in memory. In R. C. Anderson, R. J. Spiro, & W. E. Montague (Eds.), Schooling and the Acquisition of Knowledge (pp. 99-135). Erlbaum.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185 (4157), 1124-1131.

Thibaut, J., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups . New York: Wiley.

Tolman, E. C., Hall, C. S., & Bretnall, E. P. (1932). A disproof of the law of effect and a substitution of the laws of emphasis, motivation and disruption. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 15(6) , 601.

Tolman E. C. (1948). Cognitive maps in rats and men . Psychological Review. 55, 189–208

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory (pp. 381-403). Academic Press.

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics or control and communication in the animal and the machine . Paris, (Hermann & Cie) & Camb. Mass. (MIT Press).

Further Reading

- Why Your Brain is Not a Computer

- Cognitive Psychology Historial Development

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Treatment of Limerence Using a Cognitive Behavioral Approach: A Case Study

Brandy e wyant , mph, msw, lcsw.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Brandy E Wyant, Independent Researcher, Arlington, MA, USA. Email: [email protected]

Collection date 2021.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Limerence is an underresearched condition of unknown prevalence that causes significant loss of productivity and emotional distress to sufferers. Individuals with limerence display an obsessive attachment to a particular person or “limerent object” (LO) that interferes with daily functioning and the formation and maintenance of healthy relationships. The current study proposes a conceptualization of the condition in a 28-year-old individual and describes a treatment approach using cognitive-behavioral techniques, most notably exposure responsive prevention as used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The number and type of compulsive rituals performed by the treated individual were notably decreased at 9-month follow-up after treatment, and a subjective assessment of dysfunctional thought patterns related to the LO also suggested improvement. A novel screening instrument is presented, as validated screening instruments do not yet exist. Implications for diagnosis and treatment are discussed.

Keywords: cognitive behavioral therapy, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety

Introduction

Psychologist Dorothy Tennov coined the term limerence in the early 1970s after conducting over 300 interviews to gather qualitative data on the experience of romantic love ( 1 ). Tennov noted a particular manifestation of “being in love” that many of her interviewees described in a similar way – an involuntary, overwhelming longing for another person's attention and positive regard. This attachment was typically unrequited, developing for someone unavailable to reciprocate feelings.

Uncertainty is the driving force behind the development and maintenance of limerence ( 2 ). The individual experiencing limerence feels an attraction towards a particular “limerent object” (LO) whose willingness to reciprocate is uncertain. The greater the degree of uncertainty, the more intensely the individual ruminates about the LO, and the greater the desire for reciprocation. This pattern of uncertainty about the LO's feelings and availability may distinguish limerence from the early stages of a typical romantic relationship, in which both partners often experience infatuation or obsession with each other.

Individuals experiencing limerence struggle with near-constant rumination about the LO ( 3 ). They may also engage in rituals that interfere with their other responsibilities, such as staring at photos of the LO or repeatedly reading messages from them. Frequently, the sufferer mentally replays past interactions with the LO, searching for indications of how the LO might feel towards them. When the LO shows affection or approval, the limerent individual's mood soars to ecstatic, and in the face of actual or perceived disapproval, the mood plummets to despair ( 3 ).

Wakin and Vo furthered Tennov's work with a proposed model of limerence that drew parallels with both obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and substance use disorder (SUD) yet distinguished it as a unique condition ( 3 ). Due to the presence of both intrusive thoughts and compulsive rituals, individuals experiencing limerence may meet diagnostic criteria for OCD if these thoughts and rituals cause significant distress and impairment in functioning ( 4 ). Wakin and Vo further noted that separation from the LO results in withdrawal symptoms such as pain in the chest or abdomen, sleep disturbance, irritability, and depression. Additionally, the compulsive behavior that accompanies limerence is reminiscent of a substance use disorder, namely the amount of time that is spent planning for and gaining access to the LO, even when the limerent individual is fully aware of the negative effects of this behavior ( 3 ). Fisher et al. further assert that romantic love may itself be a form of addiction, because brain scanning has revealed that feelings of intense romantic love involve the same regions of the brain, referred to as the reward center, that are also activated in behavioral addictions, for example, gambling, or SUD ( 5 ).

Tennov reported that limerent episodes may occur just once in a person's life or sequentially for a series of different limerent objects. Each episode may last for a few weeks or for decades, with the average episode lasting between 18 months and 3 years ( 1 ). Individuals of all ages and genders may be affected, and the LO is not necessarily of the same gender to which the individual is sexually attracted, implying that limerence is distinct from sexual attraction ( 6 ). As Tennov notes, “sex is neither essential nor, in itself, adequate to satisfy the limerent need…Limerence is a desire for more than sex…” [emphasis original] ( 1 ).

Clinical descriptions of the course and treatment of limerence are extremely scarce outside of Tennov's seminal book ( 1 ) and Willmott and Bentley's more recent work ( 6 ). Therefore, in the absence of established diagnostic criteria and treatment protocols for limerence, clinicians may reasonably use evidence-based treatment for OCD, most notably exposure response prevention (ERP), to treat an individual presenting with limerence. ERP is a behavioral therapy that involves deliberately exposing an individual to a feared stimulus and preventing the individual from engaging in rituals that alleviate their anxiety ( 7 , 8 ). In the case of limerence, one may imagine the feared stimulus as separation from or rejection by the LO.

Description

The current case study describes treatment incorporating exposure response prevention (ERP), cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation techniques with a 28-year old female reporting a lifelong history of limerence. The individual undergoing treatment was the author (“BW”), and therefore consent to present this case study in article format is assumed. BW began treatment for limerence with a licensed clinical social worker in March 2016 as a 28-year old single, white cisgender female. Consent for treatment was obtained prior to beginning services. BW received individual, 45 min psychotherapy sessions once every 2 weeks throughout the treatment period.

Case History

BW reported a history since the age of 4 years of a series of sequential, non-overlapping LOs. She stated that while she never felt sexual attraction toward the LO, she experienced an intense and unrelenting desire to be closer both physically and emotionally to the LO. Her past LOs were females in a mentoring role, such as camp counselors or teachers. Especially as an undergraduate college student, obsessive thoughts about her LO negatively impacted her academic performance.

Presenting Concerns

When treatment commenced, BW reported spending several hours a day ruminating about the current LO, a coworker, and past encounters with her. She spent time on social media accounts looking at photos of the LO and frequently found ways to mention the LO in conversation with others. She was comforted by reminders of the LO in the environment, for example, passing the LO's favorite restaurant, and expressed that it was important to her to know how to access the LO if she needed her. BW cited multiple negative clinical consequences of limerence, such as difficulty concentrating at work and intense mood swings in response to contact with LO (euphoria) and separation from LO (depression), consistent with descriptions by Tennov ( 1 ) and Wakin and Vo ( 3 ). BW further reported difficulty finding the motivation to date available others due to preoccupation with the LO.

Case Conceptualization

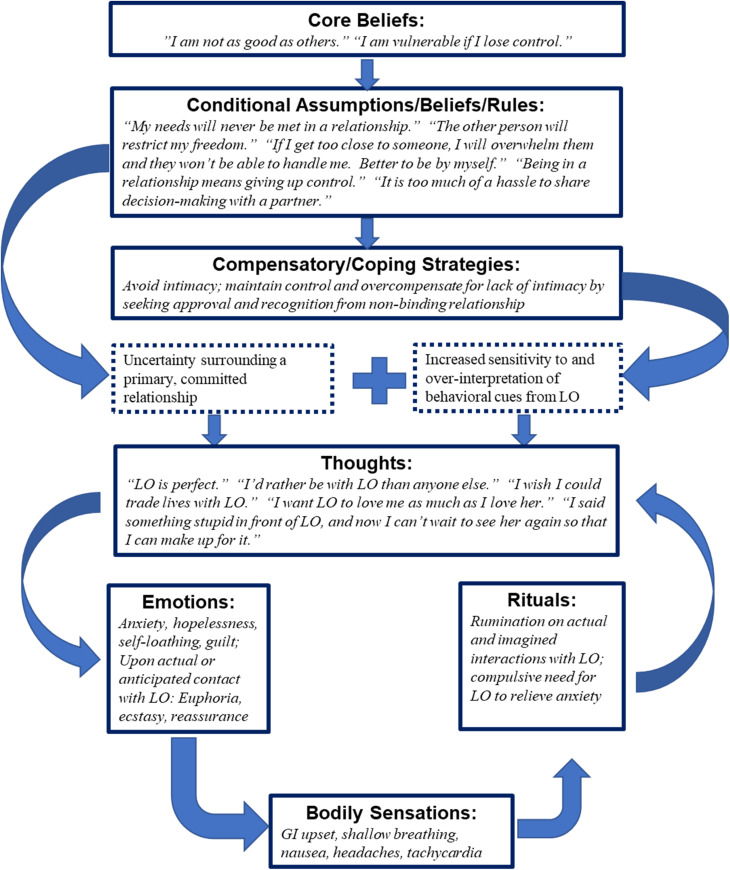

A case conceptualization diagram, adapted from Beck ( 9 ), is provided in Figure 1 . As shown in Figure 1 , BW's automatic thoughts related to limerence centered around idolization of her LO, a desire for reciprocity of feelings, and worries about how well she presented herself in front of the LO. These automatic thoughts led to unpleasant emotional and physical reactions. In response, BW engaged in rituals to increase her closeness to the LO, which brought a relief of anxiety.

Case conceptualization for development and maintenance of limerence.

Beck asserts that automatic thoughts ultimately derive from core beliefs ( 9 ). In BW's case, 2 core beliefs were identified that related to limerence: “I am not as good as others,” and “I am vulnerable if I lose control.” Beck further explains that individuals cope with negative core beliefs by developing conditional assumptions, also called intermediate beliefs ( 9 ). As shown in Figure 1 , BW's conditional assumptions centered around convincing herself that she did not want to be in a committed intimate relationship.

Treatment Approach

Session 1: baseline assessment of rituals.

BW first tracked the time spent on every “limerent ritual” that she experienced during a 2-week period using a form developed for the treatment of OCD ( 10 ). During this 2-week period, BW spent a total of over 8 h engaged in all overt rituals, and she estimated that rumination about the LO consumed between 30–90 min per day.

Sessions 2 and 3: Exposure response prevention

After monitoring the frequency of rituals for 2 weeks, BW resisted completing all rituals and tracked slip-ups. Willmott and Bentley advised that sufferers should completely avoid contact with their LO, much like an individual with SUD attempts to eliminate all use of the abused drug ( 6 ). BW was not advised similarly, as her current LO was a coworker, and she was unwilling to consider a change in her work situation for the express purpose of avoiding an LO. Therefore, treatment centered on reducing her compulsions rather than reducing contact with the LO.

Session 4: Cognitive restructuring

Wakin and Vo noted that many sufferers cope with shame over limerence by placing greater importance on the relationship with the LO ( 3 ). These idealized thoughts and beliefs serve to maintain the limerent cycle by increasing the urgency for emotional reciprocation.

BW used a list of common cognitive distortions to identify irrational thoughts and beliefs about the LO and constructed more balanced alternative statements, such as “I have had many moments of joy and fulfillment that did not involve her.”

Session 5: Behavioral activation

The remainder of treatment focused on helping BW to develop more adaptive habits that would contradict her previously held belief that she had to rely on limerent rituals for reassurance, a sense of well-being, or alleviation of boredom. BW and the therapist collaborated on a list of activities that would provide both social connection and other benefits such as physical exercise or a sense of mastery.

The self-monitoring form was repeated 9 months following its initial administration prior to the intervention. As in the first assessment, all limerent rituals were tracked for a period of 2 weeks. At follow-up, BW reduced the amount of time spent engaged in rituals from about 8 h to just 10 min, and she reduced the number of occurrences from 225 to 10 rituals.

In addition to a decrease in the number of limerent rituals that she engaged in, BW reported at 9-month follow-up that her thinking patterns about the LO had changed. While she continued to feel drawn to the LO and thought of her often, she was able to recognize her thoughts and emotions as the product of her limerence.

Validated screening instruments do not currently exist for limerence. In the weeks following her treatment for limerence, BW developed a questionnaire (see Appendix A) to assess whether her treatment gains were maintained. She self-administered the screening tool about once every 2.5 weeks for a 7-week period in August-September 2016. Results are shown in Table 1 .

Limerence Symptom Severity as Measured by Novel Screening Instrument.

Lessons Learned

Results from this case study demonstrate that exposure-response prevention, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation techniques were effective in reducing the frequency and number of compulsions as well as distorted beliefs in an individual with self-diagnosed limerence. Without a clinical definition or recognition by the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), even prevalence estimates of limerence are lacking. Treatment protocols are even more distant; most behavioral health clinicians have never heard the term “limerence,” much less knowingly treated it ( 3 ). Treatment approaches for this case were adapted from those used for anxiety disorders such as OCD.

However, limerence is in many ways distinct from OCD. While most with OCD have little ability to tolerate uncertainty, for BW, uncertainty was a driving force of the limerence. BW believed that should the LO express interest in a committed, deeper relationship, the limerence would dissipate, which is consistent with Tennov's reported observations ( 1 ). The attraction of the LO is her unavailability. As Tennov notes, “your degree of involvement increases if obstacles are externally imposed or if you doubt LO's feelings for you ( 1 ).” None of BW's LOs identified as lesbian or bisexual, and many were too many years older than she was at the time to be viable partners, for example, a 25 year-old teacher when BW was a young teenager. While not a universal experience of all individuals with limerence, BW's pattern of LOs reflects Tennov's description of “hero worship” by a young girl or woman towards an older woman ( 1 ). In addition to a desire to become physically and emotionally close to the LO, BW also experienced thoughts and feelings of idolization towards her series of LOs, whom she viewed as superior to herself in terms of personality characteristics, physical characteristics, and academic or professional achievements. She sought not only to become close to them but to emulate them. This idolization is a defining feature of limerence, though contrary to expectation, Bringle et al found that learning more information about a desired love object did not decrease obsessiveness ( 11 ).

Individuals with limerence experience a chronic, debilitating need to ruminate, idealize, and connect to the LO through rituals and compulsions. BW would often walk past or drive past an LO's home or workplace when she felt restless due to anxiety, boredom, or both. She explained that this ritual made her feel reassured that she knew how to reach the LO “if I needed her” and that her objective in walking or driving past was not to “stalk” the LO by taking note of whether she was present and what she might be doing.

BW initially demonstrated little interest in a romantic relationship, expressing a fear of losing her independence. Later in treatment, she acknowledged that her reluctance to seek out a reciprocal relationship was partly due to the sense of safety and euphoria that thoughts of the LO offered her. BW struggled to give up various safety behaviors throughout treatment, as perceived access to an LO had been consistent and reassuring throughout her life.

Limerence is distinct from the romantic or sexual attraction typically experienced by most individuals. Willmott and Bentley refuted Tennov's claim that the LO must be a potential sexual partner, noting that many limerent individuals deny sexual attraction to their LOs and experience sexual attraction to the opposite gender of the LO ( 6 ). Despite her limerent objects always having been female, BW noted that she had experienced romantic interest for males throughout her adolescence and adult life. She recounted a few specific instances of having a “crush” on an available male around her same age at the time. In each of these instances, limerence existed simultaneously for a female LO, and the thoughts and emotions associated with limerence far exceeded the intensity of her feelings of attraction for the male on which she had a crush. She would spend time fantasizing about a potential interaction with an LO in which she received a simple kind word in a passing conversation, while ignoring the potential for a more fulfilling relationship with an available partner in whom she was interested.

The present study has a few limitations. At the time of the treatment described here, no published screening instruments existed for limerence. Since then, Wolf has proposed a tool to measure limerence and conducted initial work towards validation ( 12 ). Carswell and Impett point to the lack of a consistent measure of attraction as a key limitation in the existing research on limerence ( 2 ). As this is a single case study, generalization of the results to other patients with limerence cannot be assumed before interventions are demonstrated effective in multiple trials. Additionally, a standard diagnosis of limerence does not yet exist, as it does not appear in the DSM-V. Finally, assessments of both the behavioral and cognitive symptoms of limerence were self-reported by BW and therefore subject to reporting bias and possible placebo effect.

Conclusions

This case study describes the experience of an individual experiencing obsessive thoughts and compulsive rituals intended to maintain real or imagined proximity to an attachment figure, a condition that has been called “limerence” in prior work. The individual benefitted from outpatient psychotherapy utilizing cognitive behavioral techniques, as evidenced by a subjective report of improved functioning.

Multiple descriptions of limerence's debilitating consequences exist in popular media, self-help books, and in Internet-based self-help groups ( 3 ). Despite increasing attention to the condition in recent years, the clinical community lacks validated screening instruments and treatment protocols. In fact, many mental health clinicians are largely unaware of even the concept of limerence ( 3 ). Further research is imperative to address this gap as well as to estimate the burden of limerence to society, as the financial cost of lost productivity when individuals with the condition remain untreated. Neuroimaging studies would provide evidence regarding the hypothesized similarity between limerence and substance abuse disorder. The intention of sharing this case study is to encourage these critically needed research studies as well as provide a resource for clinicians and individuals who struggle with limerence, a condition that has previously remained almost invisible to the behavioral health community.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges that the work is the author's own. This manuscript has not been previously published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. As this is a single case study, approval from an Institutional Review Board was not necessary. Because the patient in this case study was the author, no steps to ensure confidentiality were necessary.

Author Biography

Brandy E. Wyant is a clinical social worker and psychotherapist.

Original Screening Tool to Assess Symptoms of Limerence.

As you answer questions #1–8, think about the past 2 weeks.

For items #9–20, indicate how strongly you agree with the statement.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Brandy E Wyant https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5993-2801

- 1. Tennov D. Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love. New York: Stein and Day; 1979. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Carswell KL, Impett EA. What fuels passion? An integrative review of competing theories of romantic passion. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2021;15(8):e12629. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Wakin A, Vo DB. Love-variant: The Wakin-Vo model of limerence. In: Inter-Disciplinary – Net. 2nd Global Conference: Challenging Intimate Boundaries; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: Author; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Fisher HE, Xiaomeng X, Aron A, Brown LL. Intense, passionate, romantic love: a natural addiction? How the fields that investigate romance and substance abuse can inform each other. Front Psychol. 2016;7:687. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Willmott L, Bentley E. Love and limerence: Harness the limbicbrain. West Sussex: Lathbury House Limited; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ, Henk HJ. et al. Behavioral versus pharmacological treatments of obsessive compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 1998;136(3):205-16. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Steketee GS. Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Steketee GS. Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Behavioral and Cognitive Protocol for the Treatment of OCD: Therapist Protocol. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Bringle RG, Winnick T, Rydell RJ. The prevalence and nature of unrequited love. SAGE Open. 2013;3(2):1-15. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Wolf NR. Investigating limerence: Predictors of limerence, measure validation, and goal progress [Master's thesis]. [College Park: ]: University of Maryland; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.3 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This study can be used for the following topics: Localization - the role of the hippocampus in memory; Techniques to study the brain - MRI has been used to find out the exact location and size of damage to HM's brain; Bio and cognitive approach research methods - case study; Bio and cognitive approach ethical considerations - anonymity

For optimal clarity, we aim to provide a three-tiered approach to diagnosis comprising neurodegenerative clinical syndrome (e.g., primary amnesic, mixed amnesic and dysexecutive, primary progressive aphasia), level of severity (i.e., mild cognitive impairment; mild, moderate or severe dementia), and predicted underlying neuropathology (e.g., AD ...

This is a case example for the treatment of PTSD using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. It is strongly recommended by the APA Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD. Download case example (PDF, 108KB).

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of the mind as an information processor. It concerns how we take in information from the outside world, and how we make sense of that information. ... • Case studies (cognitive neuroscience) • Behavioral measures (e.g., reaction time) Assumptions ... The cognitive approach is primarily nomothetic ...

Approaches to Research : Case Study Cognitive Approach: Cognitive Processes Example Study: The Case of KF - Warrington and Shallice (1969) Aim: To investigate the possibility that short memory can be damaged without damage to the long-term ... KF case study contains a lot of quantitative data in additional to the qualitative secondary ...

the cognitive model (see the chap. 5 section entitled "Teach the Cog- nitive Model"), I mapped onto a Thought Record the situation Nancy had described to me earlier when her roommate Connie looked hurt when Nancy turned down Connie's invitation to go out to dinner (see Exhibit 7.1).

Abstract. Schwartz & Dell (2010) advocated for a major role for case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. They defined the key features of this approach and presented a number of arguments and examples illustrating the benefits of case series studies and their contribution to computational cognitive neuropsychology.

Key learning aims (1) There are high levels of co-morbid, complex mental health problems within psychiatric populations, and an increasing need for mental health practitioners to be able to work with co-morbidity effectively. (2) Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) remains one of the most well-evidenced psychological interventions with a large amount of research highlighting the effectiveness ...

In the case of limerence, one may imagine the feared stimulus as separation from or rejection by the LO. Description. The current case study describes treatment incorporating exposure response prevention (ERP), cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation techniques with a 28-year old female reporting a lifelong history of limerence.

The current study proposes a conceptualization of the condition in a 28-year-old individual and describes a treatment approach using cognitive-behavioral techniques, most notably exposure responsive prevention as used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. ... The current case study describes treatment incorporating exposure ...