- Privacy Policy

Home » Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Table of Contents

Evaluating Research

Research evaluation is a systematic process used to assess the quality, relevance, credibility, and overall contribution of a research study. Effective evaluation allows researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to determine the reliability of findings, understand the study’s strengths and limitations, and make informed decisions based on evidence. Research evaluation is crucial across disciplines, ensuring that conclusions drawn from studies are valid, meaningful, and applicable.

Why Evaluate Research?

Evaluating research provides several benefits, including:

- Ensuring Credibility : Confirms the reliability and validity of research findings.

- Identifying Limitations : Highlights potential biases, methodological flaws, or gaps.

- Promoting Accountability : Helps allocate funding and resources to high-quality studies.

- Supporting Decision-Making : Enables stakeholders to make informed decisions based on rigorous evidence.

Process of Evaluating Research

The evaluation process typically involves several steps, from understanding the research context to assessing methodology, analyzing data quality, and interpreting findings. Below is a step-by-step guide for evaluating research.

Step 1: Understand the Research Context

- Identify the Purpose : Determine the study’s objectives and research questions.

- Contextual Relevance : Evaluate the study’s relevance to current knowledge, theory, or practice.

Example : For a study examining the effects of social media on mental health, assess whether the study addresses an important and timely issue in the field of psychology.

Step 2: Assess Research Design and Methodology

- Design Appropriateness : Determine if the research design is suitable for answering the research question (e.g., experimental, observational, qualitative, or quantitative).

- Sampling : Evaluate the sample size, sampling methods, and participant selection to ensure they are representative of the population being studied.

- Variables and Measures : Review how variables were defined and measured, and ensure that the measures are valid and reliable.

Example : In an experimental study on cognitive performance, check if participants were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups to ensure the design minimizes bias.

Step 3: Evaluate Data Collection and Analysis

- Data Collection Methods : Assess the tools, procedures, and sources used for data collection. Ensure they align with the research question and minimize bias.

- Statistical Analysis : Review the statistical methods used to analyze data. Check for appropriate use of tests, proper handling of variables, and accurate interpretation of results.

- Ethics and Integrity : Consider whether data collection and analysis adhered to ethical guidelines, including participant consent, data confidentiality, and unbiased reporting.

Example : If a study uses surveys to collect data on job satisfaction, evaluate if the survey questions are clear, unbiased, and relevant to the research objectives.

Step 4: Interpret Results and Findings

- Relevance of Findings : Determine whether the findings answer the research question and contribute meaningfully to the field.

- Consistency with Existing Knowledge : Check if the results align with or contradict previous research. If they contradict, consider potential explanations for the differences.

- Generalizability : Evaluate whether the findings are applicable to a broader population or specific to the study sample.

Example : For a study on the effects of a dietary supplement on athletic performance, assess whether the findings could be generalized to athletes of different ages, genders, or skill levels.

Step 5: Assess Limitations and Biases

- Identifying Limitations : Recognize any acknowledged limitations in the study, such as small sample size, selection bias, or short duration.

- Potential Biases : Consider potential sources of bias, including researcher bias, funding source bias, or publication bias.

- Impact on Validity : Evaluate how limitations and biases might impact the study’s internal and external validity.

Example : If a study on drug efficacy was funded by a pharmaceutical company, acknowledge the potential for funding bias and whether safeguards were in place to maintain objectivity.

Step 6: Conclude with Overall Quality and Contribution

- Summarize Strengths and Weaknesses : Provide an overview of the study’s strengths and limitations, focusing on aspects that affect the reliability and applicability of the findings.

- Contribution to the Field : Assess the overall contribution to knowledge, practice, or policy, and identify any recommendations for future research or application.

Example : Conclude by summarizing whether the study’s methodology and findings are robust and suggest areas for future research, such as longer follow-up periods or larger sample sizes.

Examples of Research Evaluation

- Purpose : To assess whether stress levels affect productivity.

- Evaluation Process : Review if the sample includes participants with varying stress levels, if the stress is accurately measured (e.g., cortisol levels), and if the analysis properly accounts for confounding variables like sleep or work environment.

- Conclusion : The study could be evaluated as robust if it uses valid measures and controlled conditions, with future research suggested on different population groups.

- Purpose : To determine if digital learning tools improve student outcomes.

- Evaluation Process : Assess the appropriateness of the sample (students with similar baseline knowledge), methodology (controlled comparisons of digital vs. traditional methods), and results interpretation.

- Conclusion : Evaluate if findings are generalizable to broader educational contexts and whether technology access could be a limitation.

- Purpose : To determine the efficacy of a new medication for treating anxiety.

- Evaluation Process : Review if participants were randomly assigned, if a placebo was used, and if double-blinding was implemented to minimize bias.

- Conclusion : If the study follows a strong experimental design, it could be deemed credible. Note potential side effects for further investigation.

Methods for Evaluating Research

Several methods are used to evaluate research, depending on the type of study, objectives, and evaluation criteria. Common methods include peer review , meta-analysis , systematic reviews , and quality assessment frameworks .

1. Peer Review

Definition : Peer review is a method in which experts in the field evaluate the study before publication. They assess the study’s quality, methodology, and contribution to the field.

Advantages :

- Increases the credibility of the research.

- Provides feedback on methodological rigor and relevance.

Example : Before publishing a study on environmental sustainability, experts in environmental science review its methods, findings, and implications.

2. Meta-Analysis

Definition : Meta-analysis is a statistical technique that combines results from multiple studies to draw broader conclusions. It focuses on studies with similar research questions or variables.

- Offers a comprehensive view of a topic by synthesizing findings from various studies.

- Identifies overall trends and potential effect sizes.

Example : Conducting a meta-analysis of studies on cognitive behavioral therapy to determine its effectiveness for treating depression across diverse populations.

3. Systematic Review

Definition : A systematic review evaluates and synthesizes findings from multiple studies, providing a high-level summary of evidence on a particular topic.

- Follows a structured, transparent process for identifying and analyzing studies.

- Helps identify gaps in research, limitations, and consistencies.

Example : A systematic review of research on the impact of exercise on mental health, summarizing evidence on exercise frequency, intensity, and outcomes.

4. Quality Assessment Frameworks

Definition : Quality assessment frameworks are tools used to evaluate the rigor and validity of research studies, often using checklists or scales.

Examples of Quality Assessment Tools :

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) : Provides checklists for evaluating qualitative and quantitative research.

- GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) : Assesses the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

- PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) : A guideline for systematic reviews, ensuring clarity and transparency in reporting.

Example : Using the CASP checklist to evaluate a qualitative study on patient satisfaction with healthcare services by assessing sampling, ethical considerations, and data validity.

Evaluating research is a critical process that enables researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to determine the quality and applicability of study findings. By following a structured evaluation process and using established methods like peer review, meta-analysis, systematic review, and quality assessment frameworks, stakeholders can make informed decisions based on robust evidence. Effective research evaluation not only enhances the credibility of individual studies but also contributes to the advancement of knowledge across disciplines.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Blackwell Publishing.

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., & Altman, D. G. (2008). Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Greenhalgh, T. (2019). How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine and Healthcare (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0). The Cochrane Collaboration.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Techniques – Methods, Types and Examples

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

The Federal Evaluation Toolkit BETA

Evaluation 101.

What is evaluation? How can it help me do my job better? Evaluation 101 provides resources to help you answer those questions and more. You will learn about program evaluation and why it is needed, along with some helpful frameworks that place evaluation in the broader evidence context. Other resources provide helpful overviews of specific types of evaluation you may encounter or be considering, including implementation, outcome, and impact evaluations, and rapid cycle approaches.

What is Evaluation?

Heard the term "evaluation," but are still not quite sure what that means? These resources help you answer the question, "what is evaluation?," and learn more about how evaluation fits into a broader evidence-building framework.

What is Program Evaluation?: A Beginners Guide

Program evaluation uses systematic data collection to help us understand whether programs, policies, or organizations are effective. This guide explains how program evaluation can contribute to improving program services. It provides a high-level, easy-to-read overview of program evaluation from start (planning and evaluation design) to finish (dissemination), and includes links to additional resources.

Types of Evaluation

What's the difference between an impact evaluation and an implementation evaluation? What does each type of evaluation tell us? Use these resources to learn more about the different types of evaluation, what they are, how they are used, and what types of evaluation questions they answer.

Common Framework for Research and Evaluation The Administration for Children & Families Common Framework for Research and Evaluation (OPRE Report #2016-14). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/acf_common_framework_for_research_and_evaluation_v02_a.pdf" aria-label="Info for Common Framework for Research and Evaluation">

Building evidence is not one-size-fits all, and different questions require different methods and approaches. The Administration for Children & Families Common Framework for Research and Evaluation describes, in detail, six different types of research and evaluation approaches – foundational descriptive studies, exploratory descriptive studies, design and development studies, efficacy studies, effectiveness studies, and scale-up studies – and can help you understand which type of evaluation might be most useful for you and your information needs.

Formative Evaluation Toolkit Formative evaluation toolkit: A step-by-step guide and resources for evaluating program implementation and early outcomes . Washington, DC: Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services." aria-label="Info for Formative Evaluation Toolkit">

Formative evaluation can help determine whether an intervention or program is being implemented as intended and producing the expected outputs and short-term outcomes. This toolkit outlines the steps involved in conducting a formative evaluation and includes multiple planning tools, references, and a glossary. Check out the overview to learn more about how this resource can help you.

Introduction to Randomized Evaluations

Randomized evaluations, also known as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are one of the most rigorous evaluation methods used to conduct impact evaluations to determine the extent to which your program, policy, or initiative caused the outcomes you see. They use random assignment of people/organizations/communities affected by the program or policy to rule out other factors that might have caused the changes your program or policy was designed to achieve. This in-depth resource introduces randomized evaluations in a non-technical way, provides examples of RCTs in practice, describes when RCTs might be the right approach, and offers a thorough FAQ about RCTs.

Rapid Cycle Evaluation at a Glance Rapid Cycle Evaluation at a Glance (OPRE #2020-152). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/rapid-cycle-evaluation-glance" aria-label="Info for Rapid Cycle Evaluation at a Glance">

Rapid Cycle Evaluation (RCE) can be used to efficiently assess implementation and inform program improvement. This brief provides an introduction to RCE, describing what it is, how it compares to other methods, when and how to use it, and includes more in-depth resources. Use this brief to help you figure out whether RCE makes sense for your program.

Evaluation.gov

An official website of the Federal Government

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Evaluating Sources: General Guidelines

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Once you have an idea of the types of sources you need for your research, you can spend time evaluating individual sources. If a bibliographic citation seems promising, it’s a good idea to spend a bit more time with the source before you determine its credibility. Below are some questions to ask and things to consider as you read through a source.

Find Out What You Can about the Author

One of the first steps in evaluating a source is to locate more information about the author. Sometimes simply typing an author’s name into a search engine will give you an initial springboard for information. Finding the author’s educational background and areas of expertise will help determine whether the author has experience in what they’re writing about. You should also examine whether the author has other publications and if they are with well-known publishers or organizations.

Read the Introduction / Preface

Begin by reading the Introduction or the Preface—What does the author want to accomplish? Browse through the Table of Contents and the Index. This will give you an overview of the source. Is your topic covered in enough depth to be helpful? If you don't find your topic discussed, try searching for some synonyms in the Index.

If your source does not contain any of these elements, consider reading the first few paragraphs of the source and determining whether it includes enough information on your topic for it to be relevant.

Determine the Intended Audience

Consider the tone, style, vocabulary, level of information, and assumptions the author makes about the reader. Are they appropriate for your needs? Remember that scholarly sources often have a very particular audience in mind, and popular sources are written for a more general audience. However, some scholarly sources may be too dense for your particular research needs, so you may need to turn to sources with a more general audience in mind.

Determine whether the Information is Fact, Opinion, or Propaganda

Information can usually be divided into three categories: fact, opinion, and propaganda. Facts are objective, while opinions and propaganda are subjective. A fact is something that is known to be true. An opinion gives the thoughts of a particular individual or group. Propaganda is the (usually biased) spreading of information for a specific person, group, event, or cause. Propaganda often relies on slogans or emotionally-charged images to influence an audience. It can also involve the selective reporting of true information in order to deceive an audience.

- Fact: The Purdue OWL was launched in 1994.

- Opinion: The Purdue OWL is the best website for writing help.

- Propaganda: Some students have gone on to lives of crime after using sites that compete with the Purdue OWL. The Purdue OWL is clearly the only safe choice for student writers.

The last example above uses facts in a bad-faith way to take advantage of the audience's fear. Even if the individual claim is true, the way it is presented helps the author tell a much larger lie. In this case, the lie is that there is a link between the websites students visit for writing help and their later susceptibility to criminal lifstyles. Of course, there is no such link. Thus, when examining sources for possible propaganda, be aware that sometimes groups may deploy pieces of true information in deceptive ways.

Note also that the difference between an opinion and propaganda is that propaganda usually has a specific agenda attached—that is, the information in the propaganda is being spread for a certain reason or to accomplish a certain goal. If the source appears to represent an opinion, does the author offer legitimate reasons for adopting that stance? If the opinion feels one-sided, does the author acknowledge opposing viewpoints? An opinion-based source is not necessarily unreliable, but it’s important to know whether the author recognizes that their opinion is not the only opinion.

Identify the Language Used

Is the language objective or emotional? Objective language sticks to the facts, but emotional language relies on garnering an emotional response from the reader. Objective language is more commonly found in fact-based sources, while emotional language is more likely to be found in opinion-based sources and propaganda.

Evaluate the Evidence Listed

If you’re just starting your research, you might look for sources that include more general information. However, the deeper you get into your topic, the more comprehensive your research will need to be.

If you’re reading an opinion-based source, ask yourself whether there’s enough evidence to back up the opinions. If you’re reading a fact-based source, be sure that it doesn’t oversimplify the topic.

The more familiar you become with your topic, the easier it will be for you to evaluate the evidence in your sources.

Cross-Check the Information

When you verify the information in one source with information you find in another source, this is called cross-referencing or cross-checking. If the author lists specific dates or facts, can you find that same information somewhere else? Having information listed in more than one place increases its credibility.

Check the Timeliness of the Source

How timely is the source? Is the source twenty years out of date? Some information becomes dated when new research is available, but other older sources of information can still be useful and reliable fifty or a hundred years later. For example, if you are researching a scientific topic, you will want to be sure you have the most up-to-date information. However, if you are examining an historical event, you may want to find primary documents from the time of the event, thus requiring older sources.

Examine the List of References

Check for a list of references or other citations that look as if they will lead you to related material that would be good sources. If a source has a list of references, it often means that the source is well-researched and thorough.

As you continue to encounter more sources, evaluating them for credibility will become easier.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Changing how we evaluate research is difficult, but not impossible

Stephen curry.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 May 7; Accepted 2020 Aug 6; Collection date 2020.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) was published in 2013 and described how funding agencies, institutions, publishers, organizations that supply metrics, and individual researchers could better evaluate the outputs of scientific research. Since then DORA has evolved into an active initiative that gives practical advice to institutions on new ways to assess and evaluate research. This article outlines a framework for driving institutional change that was developed at a meeting convened by DORA and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The framework has four broad goals: understanding the obstacles to changes in the way research is assessed; experimenting with different approaches; creating a shared vision when revising existing policies and practices; and communicating that vision on campus and beyond.

Research organism: None

Introduction

Declarations can inspire revolutionary change, but the high ideals inspiring the revolution must be harnessed to clear guidance and tangible goals to drive effective reform. When the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) was published in 2013, it catalogued the problems caused by the use of journal-based indicators to evaluate the performance of individual researchers, and provided 18 recommendations to improve such evaluations. Since then, DORA has inspired many in the academic community to challenge long-standing research assessment practices, and over 150 universities and research institutions have signed the declaration and committed to reform.

But experience has taught us that this is not enough to change how research is assessed. Given the scale and complexity of the task, additional measures are called for. We have to support institutions in developing the processes and resources needed to implement responsible research assessment practices. That is why DORA has transformed itself from a website collecting signatures to a broader campaigning initiative that can provide practical guidance. This will help institutions to seize the opportunities created by the momentum now building across the research community to reshape how we evaluate research.

Systemic change requires fundamental shifts in policies, processes and power structures, as well as in deeply held norms and values. Those hoping to drive such change need to understand all the stakeholders in the system: in particular, how do they interact with and depend on each other, and how do they respond to internal and external pressures? To this end DORA and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) convened a meeting in October 2019 that brought together researchers, university administrators, librarians, funders, scientific societies, non-profits and other stakeholders to discuss these questions. Those taking part in the meeting ( https://sfdora.org/assessingresearch/agenda/ ) discussed emerging policies and practices in research assessment, and how they could be aligned with the academic missions of different institutions.

The discussion helped to identify what institutional change could look like, to surface new ideas, and to formulate practical guidance for research institutions looking to embrace reform. This guidance – summarized below – provides a framework for action that consists of four broad goals: i) understand obstacles that prevent change; ii) experiment with different ideas and approaches at all levels; iii) create a shared vision for research assessment when reviewing and revising policies and practices; iv) communicate that vision on campus and externally to other research institutions.

Understand obstacles that prevent change

Most academic reward systems rely on proxy measures of quality to assess researchers. This is problematic when there is an over-reliance on these proxy measures, particularly so if aggregate measures are used that mask the variations between individuals and individual outputs. Journal-based metrics and the H-index, alongside qualitative notions of publisher prestige and institutional reputation, present obstacles to change that have become deeply entrenched in academic evaluation. This has happened because such measures contain an appealing kernel of meaning (though the appeal only holds so long as one operates within the confines of the law of averages) and because they provide a convenient shortcut for busy evaluators. Additionally, the over-reliance on proxy measures that tend to be focused on research can discourage researchers from working on other activities that are also important to the mission of most research institutions, such as teaching, mentoring, and work that has societal impact.

Rethinking research assessment therefore means addressing the privilege that exists in academia, and taking proper account of how luck and opportunity can influence decision-making more than personal characteristics such as talent, skill and tenacity.

The use of proxy measures also preserves biases against scholars who still feel the force of historical and geographical exclusion from the research community. Progress toward gender and race equality has been made in recent years, but the pace of change remains unacceptably slow. A recent study of basic science departments in US medical schools suggests that under current practices, a level of faculty diversity representative of the national population will not be achieved until 2080 ( Gibbs et al., 2016 ).

Rethinking research assessment therefore means addressing the privilege that exists in academia, and taking proper account of how luck and opportunity can influence decision-making more than personal characteristics such as talent, skill and tenacity. As a community, we need to take a hard look – without averting our gaze from the prejudices that attend questions of race, gender, sexuality, or disability – at what we really mean when we talk about 'success' and 'excellence' if we are to find answers congruent with our highest aspirations.

This is by no means easy. Many external and internal pressures stand in the way of meaningful change. For example, institutions have to wrestle with university rankings as part of research assessment reform, because stepping away from the surrogate, selective, and incomplete 'measures' of performance totted up by rankers poses a reputational threat. Grant funding, which is commonly seen as an essential signal of researcher success, is clearly crucial for many universities and research institutions: however, an overemphasis on grants in decisions about hiring, promotion and tenure incentivizes researchers to discount other important parts of their job. The huge mental health burden of hyper-competition is also a problem that can no longer be ignored ( Wellcome, 2020a ).

Experiment with different ideas and approaches at all levels

Culture change is often driven by the collective force of individual actions. These actions take many forms, but spring from a common desire to champion responsible research assessment practices. At the DORA/HHMI meeting Needhi Bhalla (University of California, Santa Cruz) advocated strategies that have been proven to increase equity in faculty hiring – including the use of diversity statements to assess whether a candidate is aligned with the department's equity mission – as part of a more holistic approach to researcher evaluation ( Bhalla, 2019 ). She also described how broadening the scope of desirable research interests in the job descriptions for faculty positions in chemistry at the University of Michigan resulted in a two-fold increase of applicants from underrepresented groups ( Stewart and Valian, 2018 ). As a further step, Bhalla's department now includes untenured assistant professors in tenure decisions: this provides such faculty with insights into the tenure process.

The seeds planted by individual action must be encouraged to grow, so that discussions about research assessment can reach across the entire institution.

The actions of individual researchers, however exemplary, are dependent on career stage and position: commonly, those with more authority have more influence. As chair of the cell biology department at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Sandra Schmid used her position to revise their hiring procedure to focus on key research contributions, rather than publication or grant metrics, and to explore how the applicant's future plans might best be supported by the department. According to Schmid, the department's job searches were given real breadth and depth by the use of Skype interviews (which enhanced the shortlisting process by allowing more candidates to be interviewed) and by designating faculty advocates from across the department for each candidate ( Schmid, 2017 ). Another proposal for shifting the attention of evaluators from proxies to the content of an applicant's papers and other contributions is to instruct applicants for grants and jobs to remove journal names from CVs and publication lists ( Lobet, 2020 ).

The seeds planted by individual action must be encouraged to grow, so that discussions about research assessment can reach across the entire institution. This is rarely straightforward, given the size and organizational autonomy within modern universities, which is why some have set up working groups to review their research assessment policies and practices. At the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) and Imperial College London, for example, the working groups produced action plans or recommendations that have been adopted by the university and are now being implemented ( UOC, 2019 ; Imperial College, 2020 ). University Medical Center (UMC) Utrecht has gone a step further: in addition to revising its processes and criteria for promotion and for internal evaluation of research programmes ( Benedictus et al., 2016 ), it is undertaking an in-depth evaluation of how the changes are impacting their researchers (see below).

To increase their chances of success these working groups need to ensure that women and other historically excluded groups have a voice. It is also important that the viewpoints of administrators, librarians, tenured and non-tenured faculty members, postdocs, and graduate students are all heard. This level of inclusion is important because when communities impacted by new practices are involved in their design, they are more likely to adopt them. But the more views there are around the table, the more difficult it can be to reach a consensus. Everyone brings their own frame-of-reference, their own ideas, and their own experiences. To help ensure that working groups do not become mired in minutiae, their objectives should be defined early in the process and should be simple, clear and realistic.

Create a shared vision

Aligning policies and practices with an institution's mission.

The re-examination of an institution's policies and procedures can reveal the real priorities that may be glossed over in aspirational mission statements. Although the journal impact factor (JIF) is widely discredited as a tool for research assessment, more than 40% of research-intensive universities in the United States and Canada explicitly mention the JIF in review, promotion, and tenure documents ( McKiernan et al., 2019 ). The number of institutions where the JIF is not mentioned in such documents, but is understood informally to be a performance criterion, is not known. A key task for working groups is therefore to review how well the institution's values, as expressed in its mission statement, are embedded in its hiring, promotion, and tenure practices. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are increasingly advertised as core values, but work in these areas is still often lumped into the service category, which is the least recognized type of academic contribution when it comes to promotion and tenure ( Schimanski and Alperin, 2018 ).

A complicating factor here is that while mission statements publicly signal organizational values, the commitments entailed by those statements are delivered by individuals, who are prone to unacknowledged biases, such as the perception gap between what people say they value and what they think others hold most dear. For example, when Meredith Niles and colleagues surveyed faculty at 55 institutions, they found that academics value readership most when selecting where to publish their work ( Niles et al., 2019 ). But when asked how their peers decide to publish, a disconnect was revealed: most faculty members believe their colleagues make choices based on the prestige of the journal or publisher. Similar perception gaps are likely to be found when other performance proxies (such as grant funding and student satisfaction) are considered.

Bridging perception gaps requires courage and honesty within any institution – to break with the metrics game and create evaluation processes that are visibly infused with the organization's core values. To give one example, HHMI tries to advance basic biomedical research for the benefit of humanity by setting evaluation criteria that are focused on quality and impact. To increase transparency, these criteria are now published ( HHMI, 2019 ). As one element of the review, HHMI asks Investigators to "choose five of their most significant articles and provide a brief statement for each that describes the significance and impact of that contribution." It is worth noting that both published and preprint articles can be included. This emphasis on a handful of papers helps focus the review evaluation on the quality and impact of the Investigator's work.

Generic terms like 'world-class' or 'excellent' appear to provide standards for quality; however, they are so broad that they allow evaluators to apply their own definitions, creating room for bias.

Arguably, universities face a stiffer challenge here. Institutions striving to improve their research assessment practices will likely be casting anxious looks at what their competitors are up to. However, one of the hopeful lessons from the October meeting is that less courage should be required – and progress should be faster – if institutions come together to collaborate and establish a shared vision for the reform of research evaluation.

Finding conceptual clarity

Conceptual clarity in hiring, promotion, and tenure policies is another area for institutions to examine when aligning practices with values ( Hatch, 2019 ). Generic terms like 'world-class' or 'excellent' appear to provide standards for quality; however, they are so broad that they allow evaluators to apply their own definitions, creating room for bias. This is especially the case when, as is still likely, there is a lack of diversity in decision-making panels. The use of such descriptors can also perpetuate the Matthew Effect, a phenomenon in which resources accrue to those who are already well resourced. Moore et al., 2017 have critiqued the rhetoric of 'excellence' and propose instead focusing evaluation on more clearly defined concepts such as soundness and capacity-building. (See also Belcher and Palenberg, 2018 for a discussion of the many meanings of the words 'outputs', 'outcomes' and 'impacts' as applied to research in the field of international development).

Establishing standards

Institutions should also consider conceptual clarity when structuring the information requested from those applying for jobs, promotion, or funding. There have been some interesting innovations in recent years from institutions seeking to advance more holistic forms of researcher evaluation. UMC Utrecht, the Royal Society, the Dutch Research Council (NWO), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) are also experimenting with structured narrative CV formats ( Benedictus et al., 2016 ; Gossink-Melenhorst, 2019 ; Royal Society, 2020 ; SNSF, 2020 ). These can be tailored to institutional needs and values. The concise but consistently formatted structuring of information in such CVs facilitates comparison between applicants and can provide a richer qualitative picture to complement more the quantitative aspects of academic contributions.

DORA worked with the Royal Society to collect feedback on its 'Resumé for Researchers' narrative CV format, where, for example, the author provides personal details (e.g., education, key qualification and relevant positions), a personal statement, plus answers to the following four questions: how have you contributed to the generation of knowledge?; how have you contributed to the development of individuals?; how have you contributed to the wider research community?; how have you contributed to broader society? ( The template also asks about career breaks and other factors "that might have affected your progression as a researcher"). The answers to these questions will obviously depend on the experience of the applicant but, as Athene Donald of Cambridge University has written: "The topics are broad enough that most people will be able to find something to say about each of them. Undoubtedly there is still plenty of scope for the cocky to hype their life story, but if they can only answer the first [question], and give no account of mentoring, outreach or conference organization, or can't explain why what they are doing is making a contribution to their peers or society, then they probably aren't 'excellent' after all" ( Donald, 2020 ).

It is too early to say if narrative CVs are having a significant impact, but according to the NWO their use has led to an increased consensus between external evaluators and to a more diverse group of researchers being selected for funding ( DORA, 2020 ).

Even though the imposition of structure promotes consistency, there is a confounding factor of reviewer subjectivity. At the meeting, participants identified a two-step strategy to reduce the impact of individual subjectivity on decision-making. First, evaluators should identify and agree on specific assessment criteria for all the desired capabilities. The faculty in the biology department at University of Richmond, for example, discuss the types of expertise, experience, and characteristics desired for a role before soliciting applications.

This lays the groundwork for the second step, which is to define the full range of performance standards for criteria to be used in the evaluation process. An example is the three-point rubric used by the Office for Faculty Equity and Welfare at University of California, Berkeley, which helps faculty to judge the commitment of applicants to advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion ( UC Berkeley, 2020 ). A strong applicant is one who "describes multiple activities in depth, with detailed information about both their role in the activities and the outcomes. Activities may span research, teaching and service, and could include applying their research skills or expertise to investigating diversity, equity and inclusion." A weaker candidate, on the other hand, is someone who provides "descriptions of activities that are brief, vague, or describe being involved only peripherally."

Recognizing collaborative contributions

Researcher evaluation is rightly preoccupied with the achievements of individuals, but increasingly, individual researchers are working within teams and collaborations. The average number of authors per paper has been increasing steadily since 1950 ( National Library of Medicine, 2020 ). Teamwork is essential to solve the most complex research and societal challenges, and is often mentioned as a core value in mission statements, but evaluating collaborative contributions and determining who did what remains challenging. In some disciplines, the order of authorship on a publication can signal how much an individual has contributed; but, as with other proxies, it is possible to end up relying more on assumptions than on information about actual contributions.

More robust approaches to the evaluation of team science are being introduced, with some aimed at behavior change. For example, the University of California Irvine has created guidance for researchers and evaluators on how team science should be described and assessed ( UC Irvine, 2019 ). In a separate development, led by a coalition of funders and universities, the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) system ( https://credit.niso.org ), which provides more granular insight into individual contributions to published papers, is being adopted by many journal publishers. But new technological solutions are also needed. For scientific papers, it is envisioned that authorship credit may eventually be assigned at a figure level to identify who designed, performed, and analyzed specific experiments for a study. Rapid Science is also experimenting with an indicator to measure effective collaboration ( http://www.rapidscience.org/about/ ).

Communicate the vision on campus and externally

Although many individual researchers feel constrained by an incentive system over which they have little control, at the institutional level and beyond they can be informed about and involved in the critical re-examination of research assessment. This is crucial if policy changes are to take root, and can happen in different ways, during and after the deliberations of the working groups described above. For example, University College London (UCL) held campus-wide and departmental-level consultations in drafting and reviewing new policies on the responsible use of bibliometrics, part of broader moves to embrace open scholarship ( UCL, 2018 ; Ayris, 2020 ). The working group at Imperial College London organized a symposium to foster a larger conversation within and beyond the university about implementing its commitment to DORA ( Imperial College, 2018 ).

Other institutions and departments have organized interactive workshops or invited speakers who advocate fresh thinking on research evaluation. UMC Utrecht, one of the most energetic reformers of research assessment, hosted a series of town hall meetings to collect faculty and staff input before formalizing its new policies. It is also working with social scientists from Leiden University to monitor how researchers at UMC are responding to the changes. Though the work is yet to be completed, they have identified three broad types of response: i) some researchers have embraced change and see the positive potential of aligning assessment criteria with real world impact and the diversity of academic responsibilities; ii) some would prefer to defend a status quo that re-affirms the value of more traditional metrics; iii) some are concerned about the uncertainty that attends the new norms for their assessment inside and outside UMC ( Benedictus et al., 2019 ). This research serves to maintain a dialogue about change within the institution and will help to refine the content and implementation of research assessment practices. However, the changes have already empowered PhD students at UMC to reshape their own evaluation by bringing a new emphasis on research competencies and professional development to the assessment of their performance ( Algra et al., 2020 ).

We encourage institutions and departments to publish information about their research assessment policies and practices so that research staff can see what is expected of them and, in turn, hold their institutions to account.

The Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) has executed a similarly deep dive into its research culture. In 2017, as part of efforts to improve its research and research assessment practices, it established the QUEST (Quality-Ethics-Open Science-Translation) Center in and launched a programme of work that combined communication, new incentives and new tools to foster institutional culture change ( Strech et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a researcher applying for promotion at the Charité University Hospital, which is part of BIH, must answer questions about their contributions to science, reproducibility, open science, and team science, while applications for intramural funding are assessed on QUEST criteria that refer to robust research practices (such as strategies to reduce the risk of bias, and transparent reporting of methods and results). To help embed these practices independent QUEST officers attend hiring commissions and funding reviewers are required to give structured written feedback. Although the impact of these changes is still being evaluated, lessons already learned include the importance of creating a positive narrative centered on improving the value of BIH research and of combining strong leadership and tangible support with bottom-up engagement by researchers, clinicians, technicians, administrators, and students across the institute ( Strech et al., 2020 ).

Regardless of format, transparency in the communication of policy and practice is critical. We encourage institutions and departments to publish information about their research assessment policies and practices so that research staff can see what is expected of them and, in turn, hold their institutions to account. While transparency increases accountability, it has been argued that it may stifle creativity, particularly if revised policies and criteria are perceived as overly prescriptive. Such risks can be mitigated by dialogue and consultation, and we would advise institutions to emphasize the spirit, rather than the letter, of any guidance they publish.

Universities should be encouraged to share new policies and practices with one another. Research assessment reform is an iterative process, and institutions can learn from the successes and failures of others. Workable solutions may well have to be accommodated within the traditions and idiosyncrasies of different institutions. DORA is curating a collection of new practices in research assessment that institutions can use as a resource (see sfdora.org/goodpractices ), and is always interested to receive new submissions. Based on feedback from the meeting, one of us (AH) and Ruth Schmidt (Illinois Institute of Technology) have written a briefing note that helps researchers make the case for reform to their university leaders and helps institutions experiment with different ideas and approaches by pointing to five design principles for reform ( Hatch and Schmidt, 2020 ).

Looking ahead

DORA is by no means the only organization grappling with the knotty problem of reforming research evaluation. The Wellcome Trust and the INORMS research evaluation group have both recently released guidance to help universities develop new policies and practices ( Wellcome, 2020b ; INORMS, 2020 ). Such developments are aligned with the momentum of the open research movement and the greater recognition by the academy of the need to address long-standing inequities and lack of diversity. Even with new tools, aligning research assessment policies and practices to an institution's values is going to take time. There is tension between the urgency of the situation and the need to listen to and understand the concerns of the community as new policies and practices are developed. Institutions and individuals will need to dedicate time and resources to establishing and maintaining new policies and practices if academia is to succeed in its oft-stated mission of making the world a better place. DORA and its partners are committed to supporting the academic community throughout this process.

DORA receives financial support from eLife, and an eLife employee (Stuart King) is a member of the DORA steering committee.

Acknowledgements

We thank the attendees at the meeting for robust and thoughtful discussions about ways to improve research assessment. We are extremely grateful to Boyana Konforti for her keen insights and feedback throughout the writing process. Thanks also go to Bodo Stern, Erika Shugart, and Caitlin Schrein for very helpful comments, and to Rinze Benedictus, Kasper Gossink, Hans de Jonge, Ndaja Gmelch, Miriam Kip, and Ulrich Dirnagl for sharing information about interventions to improve research assessment practices at their organizations.

Biographies

Anna Hatch is the program director at DORA, Rockville, United States

Stephen Curry is Assistant Provost (Equality, Diversity & Inclusion) and Professor of Structural Biology at Imperial College, London, UK. He is also chair of the DORA steering committee

Funding Statement

No external funding was received for this work.

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Contributor Information

Anna Hatch, Email: [email protected].

Stephen Curry, Email: [email protected].

- Algra A, Koopman I, Snoek R. How young researchers can re-shape the evaluation of their work. [August 5, 2020];Nature Index. 2020 https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-young-researchers-can-re-shape-research-evaluation-universities

- Ayris P. UCL statement on the importance of open science. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/research/strategy-and-policy/ucl-statement-importance-open-science

- Belcher B, Palenberg M. Outcomes and impacts of development interventions: toward conceptual clarity. American Journal of Evaluation. 2018;39:478–495. doi: 10.1177/1098214018765698. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benedictus R, Miedema F, Ferguson MW. Fewer numbers, better science. Nature. 2016;538:453–455. doi: 10.1038/538453a. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benedictus R, Dix G, Zuijderwijk J. The evaluative breach: How research staff deal with a challenge of evaluative norms in a Dutch biomedical research institute. [July 21, 2020];2019 https://wcrif.org/images/2019/ArchiveOtherSessions/day2/62.%20CC10%20-%20Jochem%20Zuijderwijk%20-%20WCRI%20Presentation%20HK%20v5%20-%20Clean.pdf

- Bhalla N. Strategies to improve equity in faculty hiring. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2019;30:2744–2749. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E19-08-0476. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donald A. A holistic CV. [July 22, 2020];2020 http://occamstypewriter.org/athenedonald/2020/02/16/a-holistic-cv/

- DORA DORA's first funder discussion: updates from Swiss National Science Foundation, Wellcome Trust and the Dutch Research Council. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://sfdora.org/2020/04/14/doras-first-funder-discussion-updates-from-swiss-national-science-foundation-wellcome-trust-and-the-dutch-research-council/

- Gibbs KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA. Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. eLife. 2016;5:e21393. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21393. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gossink-Melenhorst K. Quality over quantity: How the Dutch Research Council is giving researchers the opportunity to showcase diverse types of talent. [July 21, 2020];2019 https://sfdora.org/2019/11/14/quality-over-quantity-how-the-dutch-research-council-is-giving-researchers-the-opportunity-to-showcase-diverse-types-of-talent/

- Hatch A. To fix research assessment, swap slogans for definitions. Nature. 2019;576:9. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03696-w. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatch A, Schmidt R. Rethinking research assessment: ideas for action. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://sfdora.org/2020/05/19/rethinking-research-assessment-ideas-for-action/

- HHMI Review of HHMI investigators. [July 21, 2020];2019 https://www.hhmi.org/programs/biomedical-research/investigator-program/review

- Imperial College Mapping the future of research assessment at imperial college London. [July 21, 2020];2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IpKyN-cXHL4

- Imperial College Research evaluation. [July 21, 2020];2020 http://www.imperial.ac.uk/research-and-innovation/about-imperial-research/research-evaluation/

- INORMS Research evaluation working group. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://inorms.net/activities/research-evaluation-working-group/

- Lobet G. Fighting the impact factor one CV at a time. [July 21, 2020];ecrLife. 2020 https://ecrlife.org/fighting-the-impact-factor-one-cv-at-a-time/

- McKiernan EC, Schimanski LA, Muñoz Nieves C, Matthias L, Niles MT, Alperin JP. Use of the journal impact factor in academic review, promotion, and tenure evaluations. eLife. 2019;8:e47338. doi: 10.7554/eLife.47338. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore S, Neylon C, Eve MP, O'Donnell DP, Pattinson D. "Excellence R Us": University research and the fetishisation of excellence. Palgrave Communications. 2017;3:1–13. doi: 10.1057/PALCOMMS.2016.105. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Library of Medicine Number of authors per MEDLINE/PubMed citation. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/authors1.html

- Niles MT, Schimanski LA, McKiernan EC, Alperin JP. Why we publish where we do: faculty publishing values and their relationship to review promotion and tenure expectations. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/706622. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Royal Society Résumé for researchers. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/research-culture/tools-for-support/resume-for-researchers/

- Schimanski LA, Alperin JP. The evaluation of scholarship in academic promotion and tenure processes: past, present, and future. F1000Research. 2018;7:1605. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16493.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmid SL. Five years post-DORA: promoting best practices for research assessment. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2017;28:2941–2944. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e17-08-0534. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- SNSF SciCV – SNSF tests new format CV in biology and medicine. [July 21, 2020];2020 http://www.snf.ch/en/researchinFocus/newsroom/Pages/news-200131-scicv-snsf-tests-new-cv-format-in-biology-and-medicine.aspx

- Stewart AJ, Valian V. An Inclusive Academy: Achieving Diversity and Excellence. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strech D, Weissgerber T, Dirnagl U, QUEST Group Improving the trustworthiness, usefulness, and ethics of biomedical research through an innovative and comprehensive institutional initiative. PLOS Biology. 2020;18:e3000576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000576. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UC Berkeley Support for faculty search committees. [July 21, 2020];2020 https://ofew.berkeley.edu/recruitment/contributions-diversity/support-faculty-search-committees

- UC Irvine Identifying faculty contributions to collaborative scholarship. [July 21, 2020];2019 https://ap.uci.edu/faculty/guidance/collaborativescholarship/

- UCL UCL bibliometrics policy. [July 21, 2020];2018 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/research-support/bibliometrics/ucl-bibliometrics-policy

- UOC The UOC signs the san francisco declaration to encourage changes in research assessment. [July 21, 2020];2019 https://www.uoc.edu/portal/en/news/actualitat/2019/120-dora.html

- Wellcome What researchers think about the culture they work in. [July 21, 2020];2020a https://wellcome.ac.uk/reports/what-researchers-think-about-research-culture

- Wellcome Guidance for research organisations on how to implement the principles of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment. [July 21, 2020];2020b https://wellcome.ac.uk/how-we-work/open-research/guidance-research-organisations-how-implement-dora-principles

- View on publisher site

- PDF (224.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance

Kathryn skivington, lynsay matthews, sharon anne simpson, peter craig, janis baird, jane m blazeby, kathleen anne boyd, david p french, emma mcintosh, mark petticrew, jo rycroft-malone, martin white, laurence moore.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to: K Skivington [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2021 Aug 9; Collection date 2021.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

The UK Medical Research Council’s widely used guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions has been replaced by a new framework, commissioned jointly by the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research, which takes account of recent developments in theory and methods and the need to maximise the efficiency, use, and impact of research.

Complex interventions are commonly used in the health and social care services, public health practice, and other areas of social and economic policy that have consequences for health. Such interventions are delivered and evaluated at different levels, from individual to societal levels. Examples include a new surgical procedure, the redesign of a healthcare programme, and a change in welfare policy. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) published a framework for researchers and research funders on developing and evaluating complex interventions in 2000 and revised guidance in 2006. 1 2 3 Although these documents continue to be widely used and are now accompanied by a range of more detailed guidance on specific aspects of the research process, 4 5 6 7 8 several important conceptual, methodological and theoretical developments have taken place since 2006. These developments have been included in a new framework commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and the MRC. 9 The framework aims to help researchers work with other stakeholders to identify the key questions about complex interventions, and to design and conduct research with a diversity of perspectives and appropriate choice of methods.

Summary points.

Complex intervention research can take an efficacy, effectiveness, theory based, and/or systems perspective, the choice of which is based on what is known already and what further evidence would add most to knowledge

Complex intervention research goes beyond asking whether an intervention works in the sense of achieving its intended outcome—to asking a broader range of questions (eg, identifying what other impact it has, assessing its value relative to the resources required to deliver it, theorising how it works, taking account of how it interacts with the context in which it is implemented, how it contributes to system change, and how the evidence can be used to support real world decision making)

A trade-off exists between precise unbiased answers to narrow questions and more uncertain answers to broader, more complex questions; researchers should answer the questions that are most useful to decision makers rather than those that can be answered with greater certainty

Complex intervention research can be considered in terms of phases, although these phases are not necessarily sequential: development or identification of an intervention, assessment of feasibility of the intervention and evaluation design, evaluation of the intervention, and impactful implementation

At each phase, six core elements should be considered to answer the following questions:

How does the intervention interact with its context?

What is the underpinning programme theory?

How can diverse stakeholder perspectives be included in the research?

What are the key uncertainties?

How can the intervention be refined?

What are the comparative resource and outcome consequences of the intervention?

The answers to these questions should be used to decide whether the research should proceed to the next phase, return to a previous phase, repeat a phase, or stop

Development of the Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions

The updated Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions is the culmination of a process that included four stages:

A gap analysis to identify developments in the methods and practice since the previous framework was published

A full day expert workshop, in May 2018, of 36 participants to discuss the topics identified in the gap analysis

An open consultation on a draft of the framework in April 2019, whereby we sought stakeholder opinion by advertising via social media, email lists and other networks for written feedback (52 detailed responses were received from stakeholders internationally)

Redraft using findings from the previous stages, followed by a final expert review.

We also sought stakeholder views at various interactive workshops throughout the development of the framework: at the annual meetings of the Society for Social Medicine and Population Health (2018), the UK Society for Behavioural Medicine (2017, 2018), and internationally at the International Congress of Behavioural Medicine (2018). The entire process was overseen by a scientific advisory group representing the range of relevant NIHR programmes and MRC population health investments. The framework was reviewed by the MRC-NIHR Methodology Research Programme Advisory Group and then approved by the MRC Population Health Sciences Group in March 2020 before undergoing further external peer and editorial review through the NIHR Journals Library peer review process. More detailed information and the methods used to develop this new framework are described elsewhere. 9 This article introduces the framework and summarises the main messages for producers and users of evidence.

What are complex interventions?

An intervention might be considered complex because of properties of the intervention itself, such as the number of components involved; the range of behaviours targeted; expertise and skills required by those delivering and receiving the intervention; the number of groups, settings, or levels targeted; or the permitted level of flexibility of the intervention or its components. For example, the Links Worker Programme was an intervention in primary care in Glasgow, Scotland, that aimed to link people with community resources to help them “live well” in their communities. It targeted individual, primary care (general practitioner (GP) surgery), and community levels. The intervention was flexible in that it could differ between primary care GP surgeries. In addition, the Link Workers did not support just one specific health or wellbeing issue: bereavement, substance use, employment, and learning difficulties were all included. 10 11 The complexity of this intervention had implications for many aspects of its evaluation, such as the choice of appropriate outcomes and processes to assess.

Flexibility in intervention delivery and adherence might be permitted to allow for variation in how, where, and by whom interventions are delivered and received. Standardisation of interventions could relate more to the underlying process and functions of the intervention than on the specific form of components delivered. 12 For example, in surgical trials, protocols can be designed with flexibility for intervention delivery. 13 Interventions require a theoretical deconstruction into components and then agreement about permissible and prohibited variation in the delivery of those components. This approach allows implementation of a complex intervention to vary across different contexts yet maintain the integrity of the core intervention components. Drawing on this approach in the ROMIO pilot trial, core components of minimally invasive oesophagectomy were agreed and subsequently monitored during main trial delivery using photography. 14

Complexity might also arise through interactions between the intervention and its context, by which we mean “any feature of the circumstances in which an intervention is conceived, developed, implemented and evaluated.” 6 15 16 17 Much of the criticism of and extensions to the existing framework and guidance have focused on the need for greater attention on understanding how and under what circumstances interventions bring about change. 7 15 18 The importance of interactions between the intervention and its context emphasises the value of identifying mechanisms of change, where mechanisms are the causal links between intervention components and outcomes; and contextual factors, which determine and shape whether and how outcomes are generated. 19

Thus, attention is given not only to the design of the intervention itself but also to the conditions needed to realise its mechanisms of change and/or the resources required to support intervention reach and impact in real world implementation. For example, in a cluster randomised trial of ASSIST (a peer led, smoking prevention intervention), researchers found that the intervention worked particularly well in cohesive communities that were served by one secondary school where peer supporters were in regular contact with their peers—a key contextual factor consistent with diffusion of innovation theory, which underpinned the intervention design. 20 A process evaluation conducted alongside a trial of robot assisted surgery identified key contextual factors to support effective implementation of this procedure, including engaging staff at different levels and surgeons who would not be using robot assisted surgery, whole team training, and an operating theatre of suitable size. 21

With this framing, complex interventions can helpfully be considered as events in systems. 16 Thinking about systems helps us understand the interaction between an intervention and the context in which it is implemented in a dynamic way. 22 Systems can be thought of as complex and adaptive, 23 characterised by properties such as emergence, feedback, adaptation, and self-organisation ( table 1 ).

Properties and examples of complex adaptive systems

For complex intervention research to be most useful to decision makers, it should take into account the complexity that arises both from the intervention’s components and from its interaction with the context in which it is being implemented.

Research perspectives

The previous framework and guidance were based on a paradigm in which the salient question was to identify whether an intervention was effective. Complex intervention research driven primarily by this question could fail to deliver interventions that are implementable, cost effective, transferable, and scalable in real world conditions. To deliver solutions for real world practice, complex intervention research requires strong and early engagement with patients, practitioners, and policy makers, shifting the focus from the “binary question of effectiveness” 26 to whether and how the intervention will be acceptable, implementable, cost effective, scalable, and transferable across contexts. In line with a broader conception of complexity, the scope of complex intervention research needs to include the development, identification, and evaluation of whole system interventions and the assessment of how interventions contribute to system change. 22 27 The new framework therefore takes a pluralistic approach and identifies four perspectives that can be used to guide the design and conduct of complex intervention research: efficacy, effectiveness, theory based, and systems ( table 2 ).

Although each research perspective prompts different types of research question, they should be thought of as overlapping rather than mutually exclusive. For example, theory based and systems perspectives to evaluation can be used in conjunction, 33 while an effectiveness evaluation can draw on a theory based or systems perspective through an embedded process evaluation to explore how and under what circumstances outcomes are achieved. 34 35 36

Most complex health intervention research so far has taken an efficacy or effectiveness perspective and for some research questions these perspectives will continue to be the most appropriate. However, some questions equally relevant to the needs of decision makers cannot be answered by research restricted to an efficacy or effectiveness perspective. A wider range and combination of research perspectives and methods, which answer questions beyond efficacy and effectiveness, need to be used by researchers and supported by funders. Doing so will help to improve the extent to which key questions for decision makers can be answered by complex intervention research. Example questions include:

Will this effective intervention reproduce the effects found in the trial when implemented here?

Is the intervention cost effective?

What are the most important things we need to do that will collectively improve health outcomes?

In the absence of evidence from randomised trials and the infeasibility of conducting such a trial, what does the existing evidence suggest is the best option now and how can this be evaluated?

What wider changes will occur as a result of this intervention?

How are the intervention effects mediated by different settings and contexts?

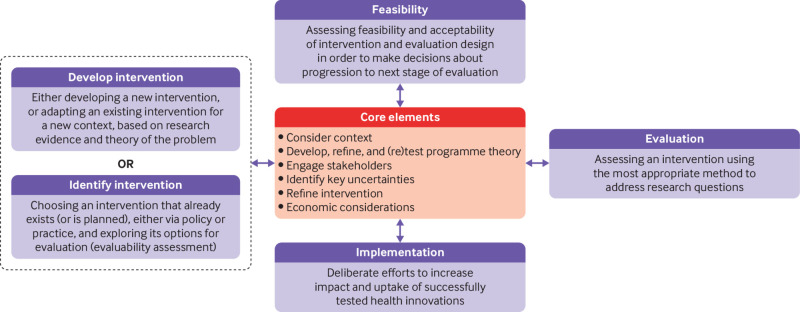

Phases and core elements of complex intervention research

The framework divides complex intervention research into four phases: development or identification of the intervention, feasibility, evaluation, and implementation ( fig 1 ). A research programme might begin at any phase, depending on the key uncertainties about the intervention in question. Repeating phases is preferable to automatic progression if uncertainties remain unresolved. Each phase has a common set of core elements—considering context, developing and refining programme theory, engaging stakeholders, identifying key uncertainties, refining the intervention, and economic considerations. These elements should be considered early and continually revisited throughout the research process, and especially before moving between phases (for example, between feasibility testing and evaluation).

Framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. Context=any feature of the circumstances in which an intervention is conceived, developed, evaluated, and implemented; programme theory=describes how an intervention is expected to lead to its effects and under what conditions—the programme theory should be tested and refined at all stages and used to guide the identification of uncertainties and research questions; stakeholders=those who are targeted by the intervention or policy, involved in its development or delivery, or more broadly those whose personal or professional interests are affected (that is, who have a stake in the topic)—this includes patients and members of the public as well as those linked in a professional capacity; uncertainties=identifying the key uncertainties that exist, given what is already known and what the programme theory, research team, and stakeholders identify as being most important to discover—these judgments inform the framing of research questions, which in turn govern the choice of research perspective; refinement=the process of fine tuning or making changes to the intervention once a preliminary version (prototype) has been developed; economic considerations=determining the comparative resource and outcome consequences of the interventions for those people and organisations affected

Core elements

The effects of a complex intervention might often be highly dependent on context, such that an intervention that is effective in some settings could be ineffective or even harmful elsewhere. 6 As the examples in table 1 show, interventions can modify the contexts in which they are implemented, by eliciting responses from other agents, or by changing behavioural norms or exposure to risk, so that their effects will also vary over time. Context can be considered as both dynamic and multi-dimensional. Key dimensions include physical, spatial, organisational, social, cultural, political, or economic features of the healthcare, health system, or public health contexts in which interventions are implemented. For example, the evaluation of the Breastfeeding In Groups intervention found that the context of the different localities (eg, staff morale and suitable premises) influenced policy implementation and was an explanatory factor in why breastfeeding rates increased in some intervention localities and declined in others. 37

Programme theory

Programme theory describes how an intervention is expected to lead to its effects and under what conditions. It articulates the key components of the intervention and how they interact, the mechanisms of the intervention, the features of the context that are expected to influence those mechanisms, and how those mechanisms might influence the context. 38 Programme theory can be used to promote shared understanding of the intervention among diverse stakeholders, and to identify key uncertainties and research questions. Where an intervention (such as a policy) is developed by others, researchers still need to theorise the intervention before attempting to evaluate it. 39 Best practice is to develop programme theory at the beginning of the research project with involvement of diverse stakeholders, based on evidence and theory from relevant fields, and to refine it during successive phases. The EPOCH trial tested a large scale quality improvement programme aimed at improving 90 day survival rates for patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery; it included a well articulated programme theory at the outset, which supported the tailoring of programme delivery to local contexts. 40 The development, implementation, and post-study reflection of the programme theory resulted in suggested improvements for future implementation of the quality improvement programme.

A refined programme theory is an important evaluation outcome and is the principal aim where a theory based perspective is taken. Improved programme theory will help inform transferability of interventions across settings and help produce evidence and understanding that is useful to decision makers. In addition to full articulation of programme theory, it can help provide visual representations—for example, using a logic model, 41 42 43 realist matrix, 44 or a system map, 45 with the choice depending on which is most appropriate for the research perspective and research questions. Although useful, any single visual representation is unlikely to sufficiently articulate the programme theory—it should always be articulated well within the text of publications, reports, and funding applications.

Stakeholders